Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 742

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 611

Struggles for Mexican Americans

Immigration from Mexico increased significantly during the war. To address labor shortages in the Southwest and on the Pacific coast, in 1942 the United States negotiated an agreement with Mexico for contract laborers (braceros) to enter the country for a limited time to work as farm laborers and in factories. From the Southwest, Mexican migrants found their way to industrial cities of the Midwest and California. Most U.S. residents of Mexican ancestry were, however, American citizens. Like other Americans, they settled into jobs to help fight the war, while more than 300,000 Mexican Americans served in the armed forces.

The war heightened Mexican Americans’ consciousness of their civil rights. As one Mexican American World War II veteran recalled: “We were Americans, not ‘spics’ or ‘greasers.’ Because when you fight for your country in a World War, against an alien philosophy, fascism, you are an American and proud to be in America.” In southern California, Ignacio Lutero Lopez, the publisher of the newspaper El Espectador (The Spectator), campaigned against segregation in movie theaters, swimming pools, and other public accommodations. He organized boycotts against businesses that discriminated against or excluded Mexican Americans. Wartime organizing led to the creation of the Unity Leagues, a coalition of Mexican American business owners, college students, civic leaders, and GIs that pressed for racial equality. In Texas, Mexican Americans joined the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), a largely middle-class group that challenged racial discrimination and segregation in public accommodations. Members of the organization emphasized the use of negotiations to redress their grievances, but when they ran into opposition, they resorted to economic boycotts and litigation. The war encouraged LULAC to expand its operations in Arizona and throughout the Southwest.

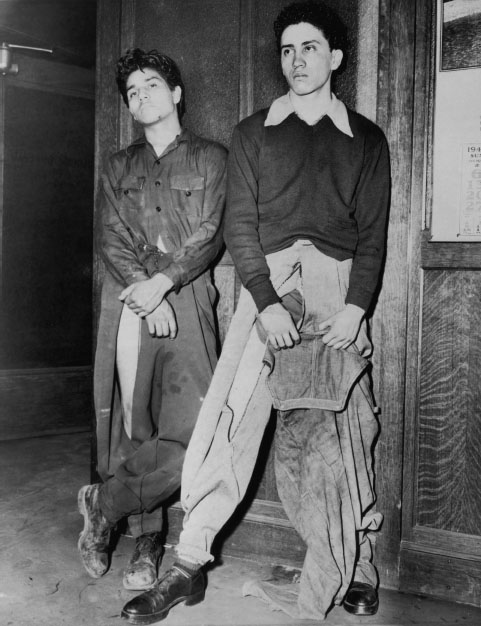

Mexican American citizens encountered hostility from recently transplanted whites and longtime residents. Tensions were greatest in Los Angeles. A small group of Mexican American teenagers joined gangs and identified themselves by wearing zoot suits—colorful, long, loose-fitting jackets with padded shoulders and baggy pants tapered at the bottom. Not all zoot-suiters were gang members, but many outside their communities failed to make this distinction. Dressed in wide-brimmed hats worn atop slicked-back hair, with pocket watches and chains dangling from their trousers, these young men offended white sensibilities of fashion and proper decorum. Sailors stationed at naval bases in southern California found their dress and swagger provocative. On the night of June 4, 1943, squads of seamen stationed in Long Beach invaded Mexican American neighborhoods in East Los Angeles, indiscriminately attacked both zoot-suiters and those not dressed in this garb on the streets, and beat them up. The police sided with the sailors and arrested Mexican American youths who tried to fight back. After four days, the zoot suit riots ended as civilian and military authorities restored order. In response, the Los Angeles city council banned the wearing of zoot suits in public and made it a criminal offense.