Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 766

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 628

The Korean War

Like Germany, Korea emerged from World War II divided between U.S. and Soviet spheres of influence. Above the 38th parallel, which divided the Korean peninsula, the Communist leader Kim Il Sung ruled North Korea with support from the Soviet Union. Below that latitude, the anti-Communist leader Syngman Rhee governed South Korea. The United States supported Rhee, but with American forces occupying Japan and the Philippines, in January 1950 Secretary of State Dean Acheson did not regard South Korea as part of the vital Asian “defense perimeter” that the United States guaranteed to protect from Communist aggression. Truman had already removed remaining American troops from the country the previous year. On June 25, 1950, an emboldened Kim Il Sung sent troops to invade South Korea, seeking to unite the country under his leadership.

In the aftermath of the invasion, Korea took on new importance to American policymakers. Drawing a parallel between the situation in Korea and the appeasement of the Nazis before World War II, Truman remarked that he had seen strong nations invade the weak before and that the failure of democracies to act only encouraged aggressors. If South Korea fell, the president believed, Communist leaders would be “emboldened to override nations closer to our own shores.” Thus the Truman Doctrine was now applied to Asia as it had previously been applied to Europe. This time, however, American financial aid would not be enough. It would be up to the U.S. military to contain the Communist threat.

Truman did not seek a declaration of war from Congress. According to Acheson, consulting Congress would delay matters and “weaken and confuse [our] will.” Instead, Truman chose a multinational course of action. With the Soviet Union boycotting the United Nations over its refusal to admit the Communist People’s Republic of China, the United States obtained authorization from the UN Security Council to send a peacekeeping force to Korea. In the absence of a declaration of war, Truman, as commander in chief, sent American troops to enforce what he called a “police action.” Fifteen other countries joined UN forces, but the United States supplied the bulk of the troops, as well as their commanding officer, General Douglas MacArthur. In reality, MacArthur reported to the president, not the United Nations.

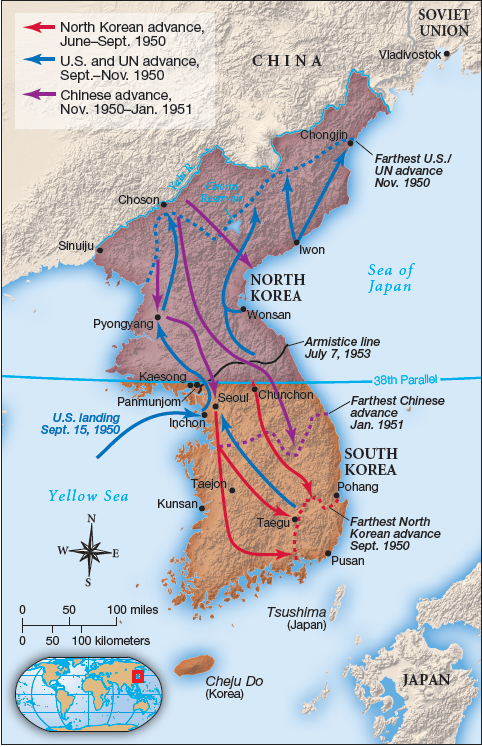

Before MacArthur could mobilize his forces, the North Koreans had penetrated most of South Korea, except for the port of Pusan on the southwest coast of the peninsula. In a daring counterattack, on September 15, 1950, MacArthur dispatched land and sea forces to capture Inchon, northwest of Pusan on the opposite coast, to cut off North Korean supply lines. Joined by UN forces pushing out of Pusan, MacArthur’s Eighth Army troops chased the enemy northward in retreat back over the 38th parallel.

Explore

See Document 24.4 for a letter from an American Red Cross worker in Korea.

Now Truman had to make a key decision. MacArthur wanted to invade North Korea, defeat the Communists, and unify the country under Syngman Rhee. Instead of sticking to his original goal of containing Communist aggression against South Korea, Truman succumbed to the lure of liberating all of Korea from the Communists. MacArthur received permission to proceed, and on October 9 his forces crossed the 38th parallel into North Korea. Within three weeks, UN troops marched through the country until they reached the Yalu River, which bordered China. With the U.S. military massed along their southern perimeter, the Chinese warned that they would send troops to repel the invaders if the Americans crossed the Yalu. Both General MacArthur and Secretary of State Acheson, based on faulty CIA intelligence, discounted this threat, figuring that the Chinese Communists did not want to fight another war so recently after winning their revolution. They were wrong. Truman approved MacArthur’s plan to cross the Yalu, and on November 27, 1950, China sent more than 300,000 troops south into North Korea. This proved disastrous for the United States; within two months, Communist troops regained control of North Korea, allowing them once again to invade South Korea. On January 4, 1951, the South Korean capital of Seoul fell to Chinese and North Korean troops (Map 24.2).

By the spring of 1951, the war had degenerated into a stalemate. UN forces succeeded in recapturing Seoul and repelling the Communists north of the 38th parallel. This time, with the American public anxious to end the war and with the presence of the Chinese promising an endless, bloody predicament, the president sought to replace combat with diplomacy. The American objective would be containment, not Korean unification.

Truman’s change of heart infuriated General MacArthur, who was willing to risk an all-out war with China and to use nuclear weapons to win. After MacArthur spoke out publicly against Truman’s policy by remarking, “There is no substitute for victory,” the president removed him from command on April 11, 1951. However, even with the change in strategy and leadership, the war dragged on for two more years until July 1953, when a final armistice agreement was reached. By this time, Truman’s term of office had ended.

The Korean War cost the United States 54,000 lives and $54 billion. This sacrifice of human lives and economic resources made the war unpopular among the American people. Few understood what good, if any, was accomplished. If American soldiers had to die and suffer, many Americans questioned why the Truman administration was satisfied with containment and not the expulsion of communism from Asia once and for all. When MacArthur returned to the United States, he was greeted as a hero, reflecting public dissatisfaction with a war in which fighting to a draw was represented as a victory.