Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 807

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 663

Eisenhower and the Cold War

In foreign affairs, Eisenhower perpetuated Truman’s containment doctrine while at the same time espousing the contradictory principle of “rolling back” communism in Eastern Europe. However, when Hungarians rose up against their Soviet-backed regime in 1956, the U.S. government did little more than offering encouragement and allowing approximately eighty thousand Hungarian refugees to enter the country. Rather than pushing back communism, the Eisenhower administration expanded the doctrine of containment around the world by entering into treaties to establish regional defense pacts. In 1954 the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization was formed to protect Australia, France, Great Britain, New Zealand, Pakistan, the Philippines, and Thailand from Communist assault. In 1959 the Central Treaty Organization brought Iraq, Iran, Turkey, and once again Pakistan within the U.S. defense perimeter.

Eisenhower’s commitment to fiscal discipline had a profound effect on his foreign policy. The president worried that the alliance among government, defense contractors, and research universities—which he dubbed “the military-industrial complex”—would bankrupt the economy and undermine individual freedom. With this in mind, he implemented the New Look strategy, which placed a higher priority on building a nuclear arsenal and delivery system than on the more expensive task of maintaining and deploying armed forces on the ground throughout the world. Nuclear missiles launched from the air by U.S. air force bombers or fired from submarines would give the United States, as Secretary of Defense Charles Wilson asserted, “a bigger bang for the buck.” With the nation now armed with nuclear weapons, the Eisenhower administration threatened “massive retaliation” in the event of Communist aggression.

The New Look may have saved money and slowed the rate of defense spending, but it had serious flaws. First, it placed a premium on “brinksmanship,” taking Communist enemies to the precipice of nuclear destruction, risking the death of millions, and hoping the other side would back down. Second, massive retaliation did not work for small-scale conflicts. For instance, in the event of a confrontation in Berlin, would the United States launch nuclear missiles toward Germany and expose its European allies in West Germany and France to nuclear contamination? Third, the buildup of nuclear warheads provoked an arms race by encouraging the Soviet Union to do the same. Peace depended on the superpowers terrifying each other with the threat of nuclear annihilation—that is, if one country attacked the other, retaliation was guaranteed to result in shared obliteration. This strategy was known as mutually assured destruction, and its acronym—MAD—summed up its nightmarish qualities. As each nuclear power increased its capacity to destroy the other many times over, the potential for mistakes and errors in judgment increased, threatening a nuclear holocaust that would leave little to rebuild. Fortunately, Eisenhower used the threat of massive retaliation judiciously, mainly against the Chinese rather than the Soviets. In 1953, after the United States threatened to deploy nuclear weapons against China, China agreed to an armistice that ended the fighting in Korea; two years later, similar American threats kept the Chinese from attacking Taiwan, where Jiang Jieshi’s Nationalist government ruled in exile.

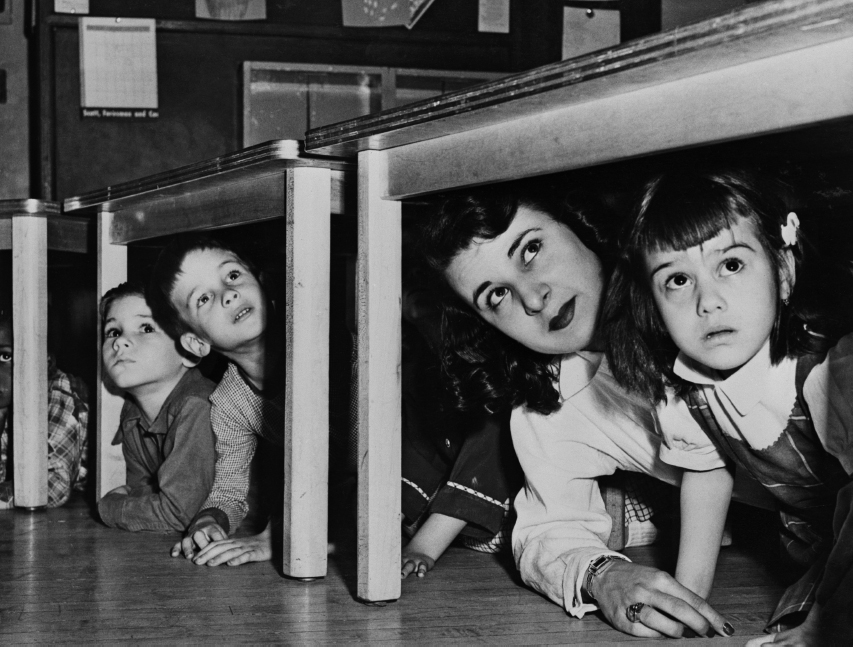

National security concerns occupied a good deal of the president’s time. Fearing that a Soviet nuclear attack could wipe out nearly a third of the population before the United States could retaliate, the Eisenhower administration stepped up civil defense efforts. Schoolchildren took part in “duck and cover” drills, in which teachers shouted “Take cover” and students hid under their desks. In the meantime, both the United States and the Soviet Union began producing intercontinental ballistic missiles armed with nuclear warheads. They also stepped up aboveground tests of nuclear weapons, which contaminated the atmosphere with dangerous radioactive particles.

Despite doomsday rhetoric of massive retaliation, Eisenhower generally relied more on diplomacy than on military action. Stalin’s death in 1953 and his eventual replacement by Nikita Khrushchev in 1955 permitted détente, or a relaxation of tensions, between the two superpowers. In July 1955, Eisenhower and Khrushchev, together with British and French leaders, gathered in Geneva to discuss arms control. It was the first meeting of an American president and a Soviet head of state since the end of World War II. Nothing concrete came out of this summit, but Eisenhower and Khrushchev did ease tensions between the two nations. In a speech to Communist officials two years later, Khrushchev denounced the excesses of Stalin’s totalitarian rule and reinforced hopes for a new era of peaceful coexistence between the Cold War antagonists. Khrushchev also visited the United States in 1959, yet peaceful coexistence remained precarious. Just as President Eisenhower was about to begin his own tour of the Soviet Union in 1960, the Soviets shot down an American U-2 spy plane flying over their country. Eisenhower canceled his trip, and tensions resumed.