Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 834

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 684

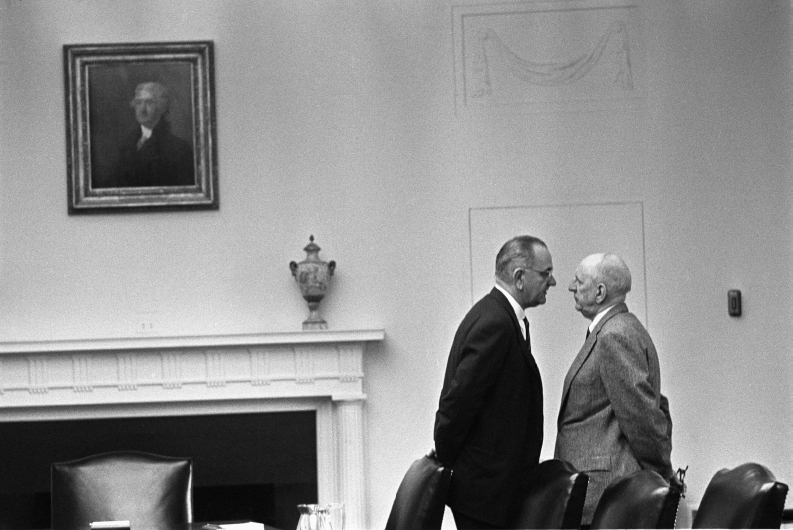

The Great Society

In an address at the University of Michigan on May 22, 1964, President Johnson sketched out his dream for the Great Society, one that “rests on abundance and liberty for all. It demands an end to poverty and racial justice, to which we are totally committed in our time. But that is just the beginning.” According to Johnson, increasing the power and wealth of America was not enough. He saw the Great Society as “a place where the city of man serves not only the needs of the body and the demands of commerce but the desire for beauty and the hunger for community.” Besides poverty and race, he outlined three broad areas in need of reform: education, the environment, and cities.

Johnson did not hesitate to approve plans to develop Kennedy’s unfinished fight against poverty. Kennedy had persuaded lawmakers to provide federal aid to poor regions such as Appalachia. In designing the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, Johnson wanted to offer the poor “a hand up, not a handout.” His program provided job training, remedial education (later to include the preschool program Head Start), a domestic Peace Corps called Volunteers in Service to America (VISTA), and a Community Action Program that empowered the poor to shape policies affecting their own communities. The antipoverty program helped reduce the proportion of poor people from 20 percent in 1963 to 13 percent five years later, and it helped reduce the rate of black poverty from 40 percent to 20 percent during this same period.

Johnson intended to fight the War on Poverty through the engine of economic growth. In 1962 Congress had passed the Revenue Act, which gave more than $1 billion in tax breaks to businesses. Kennedy had agreed to the targeted tax reduction because he believed it would encourage businesses to plow added savings into new investments and to expand production, thereby creating new jobs. Johnson’s tax cut, which applied across the board, stimulated the economy and sent the gross national product soaring from $591 billion in 1963 to $977 billion by the end of the decade. Thus the logic of economic expansion rather than redistribution guided Johnson’s War on Poverty.

Despite considerable success, Johnson’s program failed to meet liberal expectations. It would have taken an annual appropriation of about $11 billion to lift every needy person above the poverty line. To reduce opposition from cost-minded legislators who wanted to starve his programs if they could not stop them, Johnson asked Congress for just under $1 billion a year. Because the president refused to press lawmakers harder for money, his ability to fight the War on Poverty was severely limited.

Whatever the limitations, Johnson campaigned on his antipoverty and civil rights record in his bid to recapture the White House in 1964. His Republican opponent, Senator Barry M. Goldwater of Arizona, personified the conservative right wing of the Republican Party and rejected the Modern Republicanism identified with President Eisenhower (see chapter 25). The Arizona senator condemned big government, supported states’ rights, and accused liberals of not waging the Cold War forcefully enough. His aggressive conservatism appealed to his grassroots base in small-town America, especially in southern California, the Southwest, and the South. His tough rhetoric, however, scared off moderate Republicans, resulting in a landslide for Johnson on election day, as well as considerable Democratic majorities in Congress.

Flush with victory, Johnson moved quickly and achieved impressive results. To cite only a few examples, the Eighty-ninth Congress (1965–1967) provided federal aid to public schools; subsidized health care for the elderly and the poor by creating Medicare and Medicaid; expanded voting rights for African Americans in the South; authorized funds to cities for housing, jobs, education, mass transportation, crime prevention, and recreation; raised the minimum wage; created national endowments for the fine arts and humanities; and adopted regulations to preserve clean air and water supplies. The 1965 Immigration Act repealed discriminatory national origins quotas established in 1924, resulting in a shift of immigration from Europe to Asia and Central and South America (Table 26.1).

| Year | Legislation or Order | Purpose |

| 1964 | Civil Rights Act | Prohibited discrimination in public accommodations, education, and employment |

| Economic Opportunity Act | Established War on Poverty agencies: Head Start, VISTA, Job Corps, and Community Action Program | |

| 1965 | Elementary and Secondary Education Act | Federal funding for elementary and secondary schools |

| Medical Care Act | Provided Medicare health insurance for citizens 65 years and older and Medicaid health benefits for the poor | |

| Voting Rights Act | Banned literacy tests for voting, authorized federal registrars to be sent into seven southern states, and monitored voting changes in these states | |

| Executive Order 11246 | Required employers to take affirmative action to promote equal opportunity and remedy the effects of past discrimination | |

| Immigration and Nationality Act | Abolished quotas on immigration that reduced immigration from non-Western and southern and eastern European nations | |

| Water Quality Act | Established and enforced federal water quality standards | |

| Air Quality Act | Established air pollution standards for motor vehicles | |

| National Arts and Humanities Act | Established National Endowment of the Humanities and National Endowment of the Arts to support the work of scholars, writers, artists, and musicians | |

| 1966 | Model Cities Act | Approved funding for the rehabilitation of inner cities |

| 1967 | Executive Order 11375 | Expanded affirmative action regulations to include women |

| 1968 | Civil Rights Act | Outlawed discrimination in housing |