Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 839

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 690

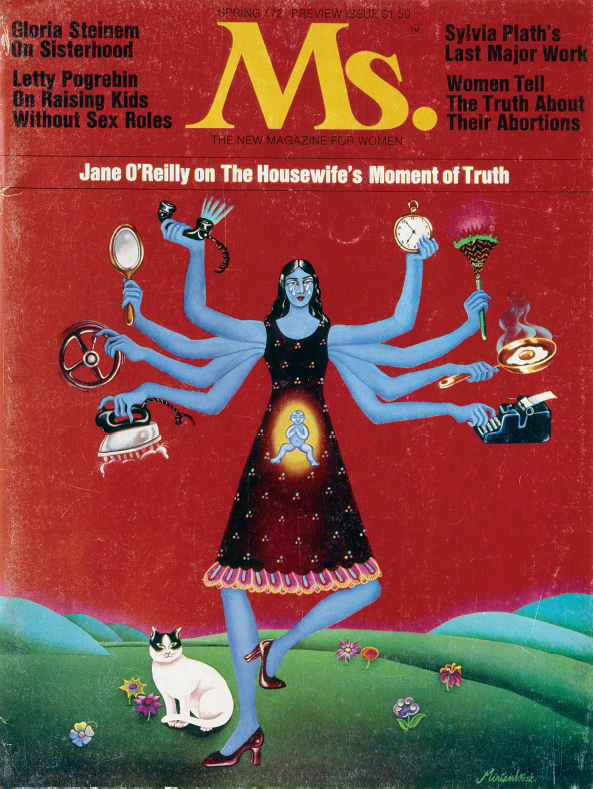

Women’s Liberation

Struggles in the 1960s for racial equality, peace, economic justice, and cultural and sexual freedom helped revive the fight for women’s emancipation. Despite passage of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920, which gave women the right to vote, women did not have equal access to employment and education or control over reproduction. Nor did they have sufficient political power to remove the remaining obstacles to full equality. By 1960 nearly 40 percent of all women held jobs—representing one-third of the labor force—and women made up 35 percent of college enrollments. Subsequently, the social movements of the 1960s—civil rights, the New Left, and the counterculture—included large numbers of women and provided them with experience, connections, principles, and grievances that would lead women to create their own movement for liberation. (See e-Document Project 26: Women’s Liberation.)

The federal government played a significant role in addressing gender discrimination. In 1961 President Kennedy appointed the Commission on the Status of Women. The commission’s report, American Women, issued in 1963, reaffirmed the primary role of women in raising the family but cataloged the inequities women faced in the workplace. In 1963 Congress passed the Equal Pay Act, which required employers to give men and women equal pay for equal work. The following year, the 1964 Civil Rights Act opened up further opportunities when it prohibited sexual bias in employment and created the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). However, women remained divided over the need for the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), first proposed in 1923 by suffragist Alice Paul. The Commission on the Status of Women refused to endorse it largely because labor union women believed that adopting the ERA would eliminate laws that specifically protected women workers with respect to hours, wages, and safety conditions.

In 1963 Betty Friedan published a landmark work in the history of the women’s rights movement, The Feminine Mystique, a book that questioned society’s prescribed gender roles. In The Feminine Mystique, she described the isolation and alienation experienced by her female friends and associates, raising the consciousness of many women, particularly college graduates and professionals. However, not all women saw themselves reflected in Friedan’s book. Many working-class women from African American and other minority families had not had the opportunity to attend college and had to work to help support their families, and younger women had not yet experienced the burdens of domestic isolation.

Nevertheless, in October 1966, Betty Friedan and like-minded women formed the National Organization for Women (NOW). With Friedan as president, NOW dedicated itself to moving society toward “true equality for all women in America, and toward a fully equal partnership of the sexes.” NOW also called on the EEOC to enforce women’s employment rights more vigorously and favored passage of the ERA, maternity leave rights in employment, the establishment of child care centers, and reproductive rights. Although NOW advocated job training programs and assistance for impoverished women, it attracted a mainly middle-class white membership. Some blacks were among its charter members, but most African American women chose to concentrate on first eliminating racial barriers that affected black women and men alike. Some union women also continued to oppose the ERA, and antiabortion advocates wanted to steer clear of NOW’s support for reproductive rights. Despite these concerns, between 1966 and 1971 NOW’s membership increased dramatically from 1,000 to 15,000.

Supporters of women’s equality drew lessons from the black freedom struggle. SNCC empowered women staff through community-organizing projects, but even within the civil rights movement women had not always been treated equally, often being assigned clerical duties. Women came up against even greater discrimination in the antiwar movement. Men held a higher status in such groups because women were not eligible for the draft. Ironically, men’s claims of moral advantage justified many of them in seeking sexual favors. “Girls say yes to guys who say no,” quipped draft-resisting men who sought to put women in their traditional sexual place.

As a result of these experiences, radical women formed their own, mainly local organizations. They created “consciousness-raising” groups that allowed them to share their experiences of oppression in the household, the workplace, the university, and movement organizations. These women’s liberationists went beyond NOW’s emphasis on legal equality and attacked male domination, or patriarchy, as the primary source of women’s subordination. They criticized the nuclear family and cultural values that glorified women as the object of male sexual desires, and they protested creatively against discrimination. In 1968 radical feminists picketed the popular Miss America contest in Atlantic City, New Jersey, the epitome of male conceptions of female beauty, and set up a “Freedom Trash Can” into which they threw undergarments and cosmetics. Radical groups such as the Redstockings condemned all men as oppressors and formed separate female collectives to affirm their identities as women.

In 1973 feminists won a major battle in the Supreme Court over a woman’s right to control reproduction. In Roe v. Wade, the high court ruled that states could not prevent a woman from obtaining an abortion in the first three months of pregnancy but could impose some limits in the next two trimesters. In furthering the constitutional right of privacy for women, the justices classified abortion as a private medical issue between a patient and her doctor. This decision marked a victory for a woman’s right to choose to terminate her pregnancy, but it also stirred up a fierce reaction from women and men who considered abortion to be the murder of an unborn child. Although the basic principle of the right to an abortion has remained intact, legal and cultural battles have raged to the present day.