Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 841

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 691

Power to the People

In addition to stimulating feminist consciousness, the civil rights movement emboldened other oppressed groups to emancipate themselves. African Americans led the way in influencing the liberationist struggles of Latinos, Indians, and gay men and women.

Malcolm X shaped the direction that many African Americans would take in seeking independence and power. Born Malcolm Little, he had engaged in a life of crime, which landed him in prison. Inside jail, he converted to the Nation of Islam, a religious sect based partly on Muslim teachings and partly on the belief that white people were devils (not a doctrine associated with orthodox Islam). After his release from jail, Malcolm rejected his “slave name” and substituted the letter X to symbolize his unknown African forebears. A charismatic leader, Minister Malcolm helped convert thousands of disciples in black ghettos by denouncing whites and encouraging blacks to embrace their African cultural heritage and beauty as a people. Favoring self-defense over nonviolence, he criticized civil rights leaders for failing to protect their women, their children, and themselves. After 1963, Malcolm X broke away from the Nation of Islam, visited the Middle East and Africa and accepted the teachings of traditional Islam, moderated his rhetoric against all whites as devils, but remained committed to black self-determination. He had already influenced the growing number of disillusioned young black activists when, in 1965, members of the Nation of Islam murdered him, apparently in revenge for challenging the organization.

Black militants, echoing Malcolm X’s ideas, further challenged the liberal consensus on race. They renounced King’s and Rustin’s ideas, rejecting their principles of integration and nonviolence in favor of black power and self-defense. Instead of welcoming whites within their organizations, black radicals believed that African Americans had to assert their independence from white America. In 1966 SNCC decided to expel whites and create an all-black organization. That same year, Stokely Carmichael, SNCC’s chairman, proclaimed the rallying cry of “black power” as the central goal of the freedom struggle, linking the cause of African American freedom to revolutionary conflicts in Cuba, Africa, and Vietnam.

Black power seemed menacing to most whites. Its emergence in the midst of riots in black ghettos, which erupted across the nation starting in the mid-1960s, underscored the concern. Few white Americans understood the horrific conditions that led to riots in Harlem and Rochester, New York, in 1964; in Los Angeles in 1965; and in Cleveland, Chicago, Detroit, Newark, and Tampa in the following two years. Black northerners still faced problems of high unemployment, dilapidated housing, and police mistreatment, which civil rights legislation had done nothing to correct. While whites perceived the ghetto uprisings solely as an exercise in criminal behavior, many blacks viewed the violence as an expression of political discontent—as rebellions, not riots. The Kerner Commission, appointed by President Johnson to assess urban disorders and chaired by Governor Otto Kerner of Illinois, concluded in 1968 that white racism remained at the heart of the problem: “Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal.”

New groups emerged to take up the cause of black power. In 1966 Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale, two black college students in Oakland, California, formed the Black Panther Party. Like Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael, the Panthers linked their cause to revolutionary movements around the world. Dressed in black leather, sporting black berets, and carrying guns, the Panthers appealed mainly to black men. They did not, however, rely on armed confrontation and bravado alone. The Panthers established day care centers and health facilities, which gained the admiration of many in their communities. Much of this good work was overshadowed by violent confrontations with the police, which led to the deaths of Panthers in shootouts and the imprisonment of key party officials. By the early 1970s, local and federal government crackdowns on the Black Panthers had destabilized the organization and reduced its influence.

Black militants were not the only African Americans to clash with the government. After 1965, King increasingly criticized the Johnson administration for waging war in Vietnam and failing to fight the War on Poverty more vigorously at home. In 1968 he prepared to mount a massive Poor People’s March on Washington when he was shot and killed by James Earl Ray in Memphis, where he was supporting demonstrations for striking sanitation workers. The death of King furthered black disillusionment. In the wake of his murder, riots again erupted in hundreds of cities throughout the country. Little noticed amid the fiery turbulence, President Johnson signed into law the 1968 Fair Housing Act, the final piece of civil rights legislation of his term.

The African American freedom movement inspired Latinos struggling for equality and advancement. During the 1960s, the size of the Spanish-speaking population in the United States tripled from three million to nine million. Hispanic Americans were a diverse group who hailed from many countries and backgrounds. In the 1950s, Cesar Chavez had emerged as the leader of oppressed Mexican farmworkers in California. In seeking the right to organize a union and gain higher wages and better working conditions, Chavez shared King’s nonviolent principles. In 1962 Chavez formed the National Farm Workers Association, and in 1965 the union called a strike against California grape growers, one that attracted national support and lasted five years before reaching a successful settlement.

Younger Mexican Americans, especially those in cities such as Los Angeles and other western barrios (ghettos), supported Chavez’s economic goals but challenged older political leaders who sought cultural assimilation. Borrowing from the Black Panthers, Mexican Americans formed the Brown Berets, a self-defense organization. As a sign of their increasing militancy and independence, in 1969 some 1,500 activists gathered in Denver and declared themselves Chicanos, a term that expressed their cultural pride and identity, instead of Mexican Americans. Chicanos created a new political party, La Raza Unida (The United Race), to promote their interests, and the party and its allies sponsored demonstrations to fight for jobs, bilingual education, and the creation of Chicano studies programs in colleges. Chicano and other Spanish-language communities also took advantage of the protections of the Voting Rights Act, which, in 1975, was amended to include sections of the country—from New York to California to Florida and Texas—where Hispanic literacy in English and voter registration were low.

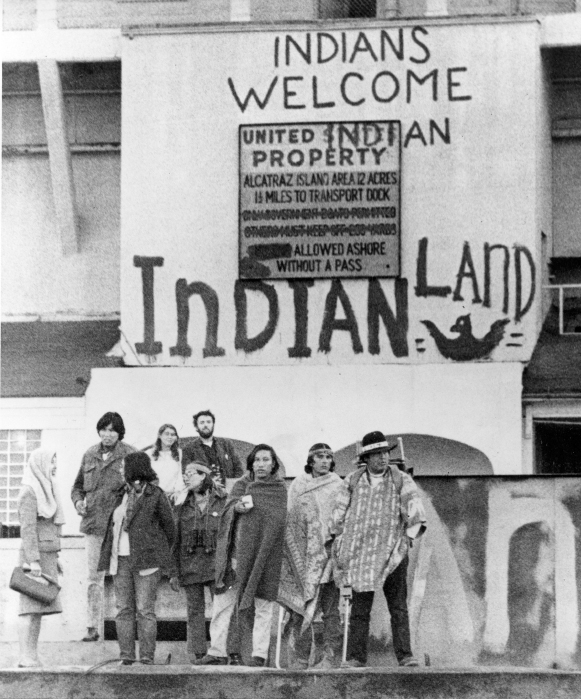

American Indians also joined the upsurge of activism and ethnic nationalism. By 1970 some 800,000 people identified themselves as American Indians, many of whom lived in poverty on reservations. They suffered from inadequate housing, high alcoholism rates, low life expectancy, staggering unemployment, and lack of education. Conscious of their heritage before the arrival of white people, determined to halt their continued deterioration, and seeking to assert “red” pride, they established the American Indian Movement (AIM) in 1968. The following year, AIM protesters occupied the abandoned prison island of Alcatraz in San Francisco Bay, where they remained until 1971. In 1972 AIM occupied the headquarters of the Federal Bureau of Indian Affairs in Washington, D.C., where protesters presented twenty demands, ranging from reparations for treaty violations to abolition of the bureau. AIM demonstrators also seized the village of Wounded Knee, South Dakota, the scene of the 1890 massacre of the Sioux residents by the U.S. army (see chapter 15), to dramatize the impoverished living conditions on the reservation. They held on for more than seventy days with eleven hostages until a shootout with the FBI ended the confrontation, killing one protester and wounding another.

Explore

See Document 26.3 for a statement on Chicano self-identity.

The results of the red power movement proved mixed. Demonstrations focused media attention on the plight of American Indians but did little to halt their downward spiral. Nevertheless, courts became more sensitive to Indian claims and protected mineral and fishing rights on reservations. Still, in the early 1970s the average annual income of American Indian families hovered around $1,500.

Unlike African Americans, Chicanos, and American Indians, homosexuals were not distinguished by the color of their skin. Estimated at 10 percent of the population, gays and lesbians remained invisible to the rest of society. Homosexuals were a target of repression during the Cold War, and the government treated them harshly and considered their sexual identity a threat to the American way of life. In the 1950s, gay men and women created their own political and cultural organizations and frequented bars and taverns outside mainstream commercial culture, but most lesbians and gay men like Bayard Rustin hid their identities. It was not until 1969 that they took a giant step toward asserting their collective grievances in a very visible fashion. Police regularly cracked down on the Stonewall Tavern in New York City’s Greenwich Village, but gay patrons battled back on June 27 in a riot that the Village Voice called “a kind of liberation, as the gay brigade emerged from the bars, back rooms, and bedrooms of the Village and became street people.” In the manner of black power and the New Left, homosexuals organized the Gay Liberation Front, voiced pride in being gay, and demanded equality of opportunity regardless of sexual orientation.

As with other oppressed groups, gays achieved victories slowly and unevenly. In the decades following the 1960s, homosexuals faced discrimination in employment, could not marry or receive domestic benefits, and were subject to violence for public displays of affection.