Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 874

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 719

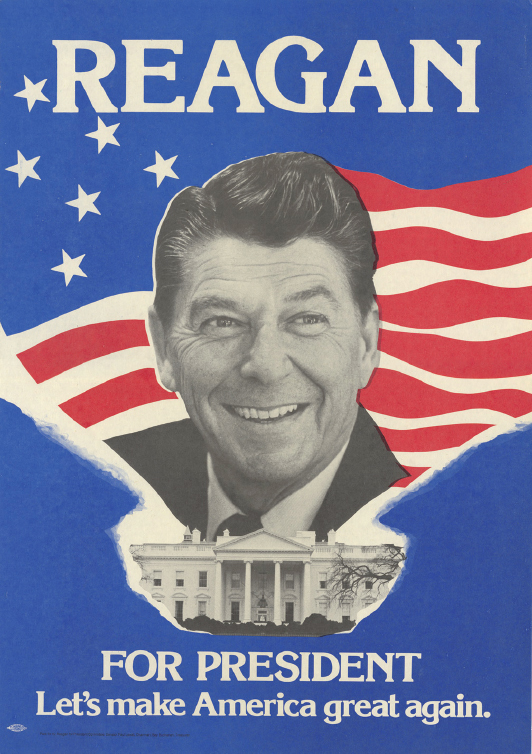

The Triumph of Ronald Reagan

Ronald Reagan’s presidential victory in 1980 consolidated the growing New Right coalition and reshaped American politics for a generation to come. The former movie actor had transformed himself from a New Deal Democrat into a conservative Republican politician when he ran for governor of California in 1966. As governor, he implemented conservative ideas of free enterprise and small government and denounced Johnson’s Great Society for threatening private property and individual liberty. “Government,” Reagan observed, “is like a baby, an alimentary canal with a big appetite at one end and no sense of responsibility at the other.” His winning combination of support for conservative economic and social issues carried him to the presidency.

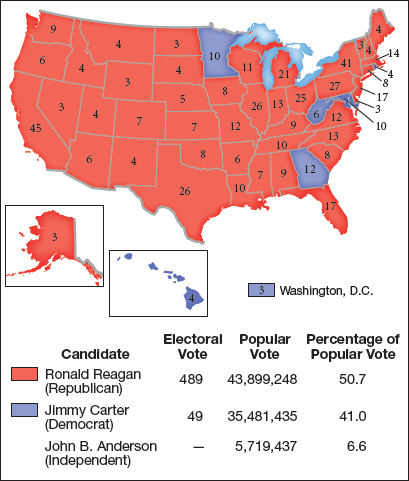

Reagan triumphed over Jimmy Carter and John Anderson, a moderate Republican who ran as an independent candidate (Map 27.3). The high unemployment and inflation of the late 1970s worked in Reagan’s favor. Reagan appealed to a coalition of conservative Republicans and disaffected Democrats, promising to cut taxes and reduce spending, to relax federal supervision over civil rights programs, and to end what was left of expensive Great Society measures and affirmative action. Finally, he energized members of the religious right, who flocked to the polls to support Reagan’s demands for voluntary prayer in the public schools, defeat of the Equal Rights Amendment, and a constitutional amendment to outlaw abortion.

Reagan’s first priority, however, was stimulating the stagnant economy. The president’s strategy, known as Reaganomics, reflected the ideas of supply-side economists and conservative Republicans. Stating that “government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem,” Reagan asked Congress for a huge income tax cut of 30 percent over three years, a reduction in spending for domestic programs of more than $40 billion, and new monetary policies to lower rising rates for loans.

The president did not operate in isolation from the rest of the world. He learned a great deal from Margaret Thatcher, the British prime minister who took office two years before Reagan. Thatcher combated inflation by slashing welfare programs, selling off publicly owned companies, and cutting back health and education programs. An advocate of supply-side economics, Thatcher reduced income taxes on the wealthy by more than 50 percent to encourage new investment. West Germany also moved toward the right under Chancellor Helmut Kohl, who reined in welfare spending. In the 1980s, Reaganomics and Thatcherism dominated the United States and the two most powerful nations of Western Europe.

In March 1981, Reagan survived a nearly fatal assassin’s bullet. More popular than ever after his recovery, the president persuaded the Democratic House and the Republican Senate to pass his economic measures in slightly modified form. The initial results were disastrous—unemployment rose to 9.5 percent in the wake of government cutbacks in spending. However, the government’s tight money policies, as engineered by the Federal Reserve Board, reduced inflation from 14 percent in 1980 to 4 percent in 1984. By 1983 the unemployment rate had also fallen, while the gross national product grew by a healthy 4.3 percent, an indication that the recession of the previous two years had ended.

The success of Reaganomics came at the expense of the poor and the lower middle class. The Reagan administration slashed federal spending by cutting benefits that affected mainly the poor and marginal workers dependent on government supplements. The president reduced spending for food stamps, school lunches, Aid to Families with Dependent Children (welfare), and Medicaid, while maintaining programs that middle-class voters relied on, such as Medicare and Social Security. However, rather than diminishing the government, the savings that came from reduced social spending went into increased military appropriations. Together with lower taxes, these expenditures benefited large corporations that received government military contracts and favorable tax write-offs.

As a result of Reagan’s economic policies, financial institutions and the stock market earned huge profits. The Reagan administration relaxed antitrust regulations, encouraging corporate mergers to a degree unseen since the Great Depression. Fueled by falling interest rates, the stock market created wealth for many investors. The number of millionaires doubled during the 1980s, as the top 1 percent of families gained control of 42 percent of the nation’s wealth and 60 percent of corporate stock. Reflecting this phenomenal accumulation of riches, television produced melodramas depicting the lives of oil barons (such as Dallas and Dynasty), whose characters lived glamorous lives filled with intrigue and extravagance. In Wall Street (1987), a film that captured the money ethic of the period, Gordon Gekko, the main character, utters the memorable line summing up the moment: “Greed, for lack of a better word, is good. Greed is right. Greed works.”

In reality, however, greed did not work for most people. The gap between the rich and the poor widened. During the 1980s, the nation’s share of poor people rose from 11.7 percent to 13.5 percent, representing 33 million Americans. Severe cutbacks in government social programs that had alleviated suffering in the past worsened the plight of the poor. Poverty disproportionately affected women and minorities. The number of homeless people grew to as many as 400,000 during the 1980s, as chronically unemployed workers, the mentally ill, and single mothers sought shelter in subways, under bridges, and in parks. While the rich got richer and the poor got poorer, the middle class diminished in size. From a high of 53 percent of families in the early 1970s, the middle class shrank to 49 percent in 1985.

The Reagan administration’s relaxed regulation of the corporate sector also contributed to the unbalanced economy. Federal agencies concerned with environmental protection, consumer product reliability, and occupational safety saw their key functions shifted to the states, which made them less effective. The president also aided big business by challenging labor unions. In 1981 air traffic controllers went on strike to gain higher wages and improved safety conditions. In response, the president fired the strikers who refused to return to work, and in their place he hired new controllers. Reagan’s anti-union actions both reflected and encouraged a decline in union membership throughout the 1980s, with union membership falling to its lowest level since the New Deal (16 percent). Without union protection, wages failed to keep up with inflation, further increasing the gap between rich and poor.

Explore

See Documents 27.3 and 27.4 on the state of the nation in the 1980s.

Reagan’s landslide victory over Democratic candidate Walter Mondale in 1984 sealed the national political transition from liberalism to conservatism. Voters responded overwhelmingly to the improving economy, Reagan’s defense of traditional social values, and his boundless optimism about America’s future. Despite the landslide, the election was notable for the nomination of Representative Geraldine Ferraro of New York as Mondale’s Democratic running mate, the first woman to run on a major party ticket for national office.

Reagan’s second term did not produce changes as significant as did his first term. Democrats still controlled the House and in 1986 recaptured the Senate. The Reagan administration focused on foreign affairs and the continued Cold War with the Soviet Union, thus escalating defense spending. Most of the Reagan economic revolution continued as before, but with serious consequences: The federal deficit mushroomed, and by 1989 the nation was saddled with a $2.8 trillion debt, a situation that jeopardized the country’s financial independence and the economic well-being of succeeding generations.

The president also reshaped the future through his nominations to the U.S. Supreme Court. Starting with the choice of Sandra Day O’Connor, the Court’s first female justice, in 1981, Reagan’s appointments moved the Court in a more conservative direction. The elevation of Associate Justice William Rehnquist to chief justice in 1986 reinforced this trend, which would have significant consequences for decades to come.