Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 861

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 702

The Election of President Nixon

The year 1968 was a turbulent one. In February, police shot indiscriminately into a crowd gathered for civil rights protests at South Carolina State University in Orangeburg, killing three students in the so-called Orangeburg massacre. The following month, student protests at Columbia University led to a violent confrontation with the New York City police. On April 4, the murder of Martin Luther King Jr. sparked an outburst of rioting by blacks in more than one hundred cities throughout the country. The assassination of Democratic presidential aspirant Robert Kennedy in June further heightened the mood of despair. Adding to the unrest, demonstrators gathered in Chicago in August at the Democratic National Convention to press for an antiwar plank in the party platform. Thousands of protesters were beaten and arrested by Chicago police officers, who violently released their frustrations on the crowds. Many Americans watched in horror as television networks broadcast the bloody clashes, but a majority of viewers sided with the police rather than the protesters.

Similar protests occurred around the world. In early 1968, university students outside of Paris protested educational policies and what they perceived as their second-class status. When students at the Sorbonne in Paris joined them in the streets, police attacked them viciously. In June, French president Charles de Gaulle sent in tanks to break up the strikes but also instituted political and economic reforms. Protests erupted during the spring in Prague, Czechoslovakia, as well. President Alexander Dubček, vowing to reform the Communist regime by initiating “socialism with a human face,” lifted press censorship, guaranteed free elections, and encouraged artists and writers to express themselves freely. Unaccustomed to such dissent and fearful it would spread to other nations within its imperial orbit, the Soviet Union sent its military into Prague in August 1968 to crush the reforms. Czechoslovakian protesters were no match for Soviet forces, and the brief experiment in freedom remembered as the “Prague Spring” came to a violent end. During the same year, student-led demonstrations erupted in Yugoslavia, Poland, West Germany, Italy, Spain, Japan, and Mexico.

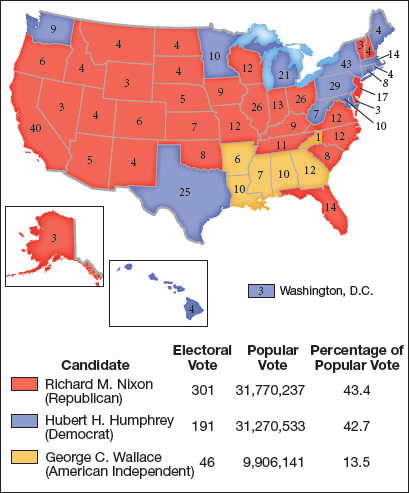

It was against this backdrop of protest, violence, and civil unrest that Richard Nixon ran for president against the Democratic nominee Hubert H. Humphrey, who was Johnson’s vice president, and the independent candidate, George C. Wallace, the segregationist governor of Alabama and a popular archconservative. To outflank Wallace on the right, Nixon appealed to disaffected Democrats as well as traditional Republicans. He declared himself the “law and order” candidate, a phrase that became a code for reining in black militancy. To win southern supporters, he pledged to ease up on enforcing federal civil rights legislation and opposed forced busing to achieve racial integration in schools. He criticized antiwar protesters and promised to end the Vietnam War with honor (without disclosing exactly how he would achieve this goal). Seeking to portray the Democrats as the party of social and cultural radicalism, Nixon geared his campaign message to the “silent majority” of voters—what one political analyst characterized as “the unyoung, the unpoor, and unblack.”

Although Nixon won 301 electoral votes, 110 more than Humphrey, none of the three candidates received a majority of the popular vote (Map 27.1). Yet Nixon and Wallace together received about 57 percent of the popular vote, a dramatic shift to the right compared with Johnson’s landslide victory just four years earlier. Nixon’s election ushered in more than two decades of Republican presidential rule, interrupted only by scandal. The New Left, which had captured the imagination of many of America’s young people, would give way to the New Right, an assortment of old and new conservatives, overwhelmingly white, who were determined to contain, if not roll back, the Great Society.