Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 913

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 748

Managing Conflict after the Cold War

The end of the Cold War left the United States as the only remaining superpower. Though Reagan’s Cold War defense spending had created huge deficits (see chapter 27), the United States emerged from the Cold War with its economic and military strength intact. With the power vacuum created by the breakup of the Soviet Union, the question remained how the United States would use its strength to preserve world order and maintain peace.

In several areas of the globe, the move toward democracy that had begun in the late 1980s proceeded peacefully into the 1990s. The oppressive, racist system of apartheid fell in South Africa, and antiapartheid activist Nelson Mandela was released after twenty-seven years in prison to become president of the country in 1994. In 1990 Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet stepped down as president of Chile and ceded control to a democratically elected candidate. That same year, the pro-Communist Sandinista government lost at the polls in Nicaragua, and in 1992 the ruling regime in El Salvador signed a peace accord with the rebels.

The end of the Cold War allowed President Bush to turn his attention to explosive issues in the Middle East. The president brought the Israelis and Palestinians together to sign an agreement providing for eventual Palestinian self-government in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. In doing so, the United States for the first time officially recognized Yasser Arafat, the head of the PLO, whom both the Israelis and the Americans had considered a terrorist.

Before Bush left the White House in 1993, he had deployed military forces in both the Caribbean and the Persian Gulf, confident that the United States could exert its influence without a challenge from the former Soviet Union. During the 1980s, the United States had developed a precarious relationship with Panamanian general Manuel Noriega. Noriega played the United States against the Soviet Union in this region that was vital to American security. Although he channeled aid to the Contras with the approval and support of the CIA, he angered the Reagan administration by maintaining close ties with Cuba. Noriega cooperated with the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency in halting shipments of cocaine from Latin America headed for the United States at the same time that he collaborated with Latin American drug kingpins to elude U.S. agents and launder the drug lords’ profits. In 1988 two Florida grand juries indicted the Panamanian leader on charges of drug smuggling and bribery, pressuring President Reagan to cut off aid to Panama and to ask Noriega to resign. Not only did Noriega refuse to step down, but he also nullified the results of the 1989 presidential election in Panama and declared himself the nation’s “maximum leader.”

After the United States tried unsuccessfully to foment an internal coup against Noriega, in 1989 the Panamanian leader proclaimed a “state of war” between the United States and his country. The situation worsened in mid-December when a U.S. marine was killed on his way home from a restaurant, allegedly by Panamanian defense forces. On December 28, 1989, President Bush launched Operation Just Cause, sending some 27,000 marines to invade Panama. Bush justified the invasion as necessary to protect the Panama Canal and the lives of American citizens, as well as to halt the drug traffic promoted by Noriega. In reality, the main purpose of the mission was to overthrow and capture the Panamanian dictator. In Operation Just Cause, the United States easily defeated a much weaker enemy. The U.S. government installed a new regime, and the marines captured Noriega and sent him back to Florida to stand trial on the drug charges. In 1992 he was found guilty and sent to prison.

Flexing military muscle in Panama was more feasible than doing so in China. President Bush believed that the acceleration of trade relations that followed full U.S. diplomatic recognition of Communist China in 1978 would prompt the kind of democratic reforms that swept through the Soviet Union in the 1980s. His expectation proved far too optimistic. In May 1989, university students in Beijing and other major cities in China held large-scale protests to demand political and economic reforms in the country. Some 200,000 demonstrators consisting of students, intellectuals, and workers gathered in the capital city’s huge Tiananmen Square, where they constructed a papier-mâché figure resembling the Statue of Liberty and sang songs borrowed from the African American civil rights movement. Deng Xiaoping, Mao Zedong’s successor, cracked down on the demonstrations by declaring martial law and dispatching the army to disperse the protesters. Peaceful activists were mowed down by machine guns and stampeded by tanks. Rather than displaying the toughness he showed in Panama, Bush merely issued a temporary ban on sales of weapons and nonmilitary items to China. When outrage over the Tiananmen Square massacre subsided, the president restored normal trade relations.

By contrast, the Bush administration’s most forceful military intervention came in Iraq. Maintaining a steady flow of oil from the Persian Gulf was vital to U.S. strategic interests. During the prolonged Iraq-Iran War in the 1980s, the Reagan administration had switched allegiance from one belligerent to the other to ensure that neither side emerged too powerful. Though the administration had orchestrated the arms-for-hostages deal with Iran, it had also courted the Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein. U.S. support for Hussein ended in 1990, after Iraq sent 100,000 troops to invade the small oil-producing nation of Kuwait, on the southern border of Iraq.

President Bush responded aggressively. He compared Saddam Hussein to Adolf Hitler and warned the Iraqis that their invasion “will not stand.” Oil was at the heart of the matter. Hussein needed to revitalize the Iraqi economy, which was devastated after a decade of war with Iran. In conquering Kuwait, which held huge oil reserves, Hussein would control one-quarter of the world output of the “black gold.” Bush feared that the Iraqi dictator would also attempt to overrun Kuwait’s neighbor Saudi Arabia, an American ally, thereby giving Iraq control of half of the world’s oil supply. Bush was also concerned that an emboldened Saddam Hussein would then upset the delicate balance of power in the Middle East and pose a threat to Israel by supporting the Palestinians. The Iraqis were rumored to be quickly developing nuclear weapons, which Hussein could use against Israel.

Rather than act unilaterally, President Bush organized a multilateral coalition against Iraqi aggression. Secretary of State James Baker persuaded the United Nations—including the Soviet Union and China, the United States’ former Cold War adversaries—to adopt a resolution calling for Iraqi withdrawal from Kuwait and imposing economic sanctions. Thirty-eight nations, including the Arab countries of Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and Kuwait, contributed 160,000 troops, roughly 24 percent of the 700,000 allied forces that were deployed in Saudi Arabia in preparation for an invasion if Iraq did not comply. Hussein’s bellicosity against an Islamic nation won him few allies in the Middle East.

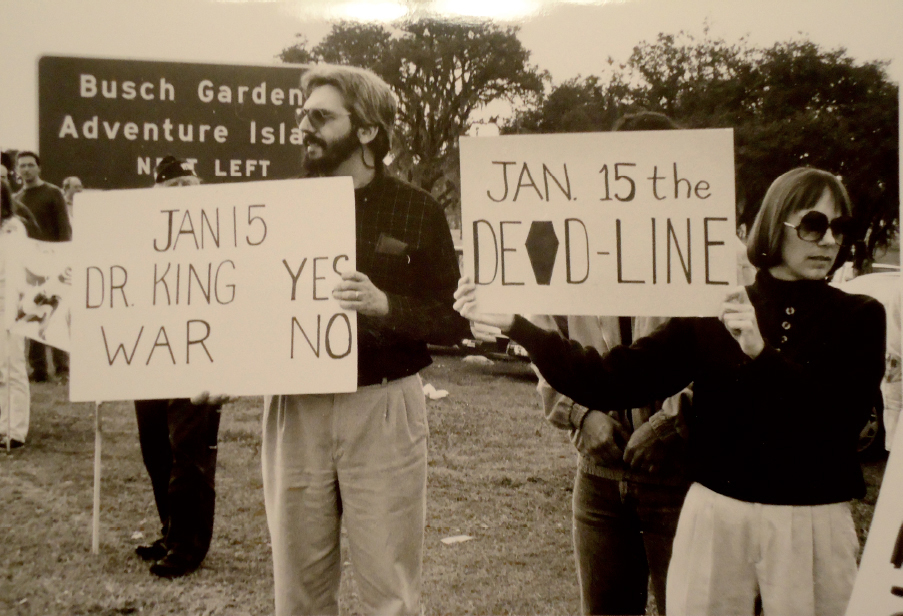

With military forces stationed in Saudi Arabia, Bush gave Hussein a deadline of January 15, 1991, to withdraw from Kuwait or else risk attack. However, the president faced serious opposition at home against waging a war for oil. Demonstrations occurred throughout the nation, and most Americans supported the continued implementation of economic sanctions, which were already causing serious hardships for the Iraqi people. In the face of widespread opposition, the president requested congressional authorization for military operations against Iraq. Lawmakers were also divided, but after long debate they narrowly approved Bush’s request.

Saddam Hussein let the deadline pass. On January 16, Operation Desert Storm began when the United States launched air attacks on Baghdad and other key targets in Iraq. After a month of bombing, Hussein still refused to capitulate, so a ground offensive was launched on February 24, 1991. Under the command of General Norman H. Schwarzkopf, more than 500,000 allied troops moved into Kuwait and easily drove Iraqi forces out of that nation; they then moved into southern Iraq. Although Hussein had confidently promised that the U.S.-led military assault would encounter the “mother of all battles,” the vastly outmatched Iraqi army, worn out from its ten-year war with Iran, was quickly defeated. Desperate for help, Hussein ordered the firing of Scud missiles on Israel to provoke it into war, which he hoped would drive a wedge between the United States and its Arab allies. Despite sustaining some casualties, Israel refrained from retaliation. The ground war ended within one hundred hours, and Iraq surrendered. An estimated 100,000 Iraqis died; by contrast, 136 Americans perished (see Map 28.1).

With the war over quickly, President Bush resisted pressure to march to Baghdad and overthrow Saddam Hussein. Bush’s stated goal had been to liberate Kuwait; he did not wish to fight a war in the heart of Iraq. The administration believed that such an expedition would involve house-to-house, urban guerrilla warfare. Marching on Baghdad would also entail battling against Hussein’s elite Republican Guard, not the weaker conscripts who had put up little resistance in Kuwait. Bush’s Arab allies opposed expanding the war, and the president did not want to risk losing their support. Finally, getting rid of Hussein might make matters worse by leaving Iran and its Muslim fundamentalist rulers the dominant power in the region. For these reasons, President Bush held Schwarzkopf’s troops in place.

The Gulf War preserved the U.S. lifeline to oil in the Persian Gulf. President Bush and his supporters concluded that the United States had the determination to make its military presence felt throughout the world. Bush and the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Colin Powell, understood that the United States had succeeded because it had pieced together a genuine coalition of nations, including Arab ones, to coordinate diplomatic and military action. Military leaders had a clear and defined mission—the liberation of Kuwait—as well as adequate troops and supplies. When they carried out their purpose, the war was over. However, American withdrawal later allowed Saddam Hussein to slaughter thousands of Iraqi rebels, including Kurds and Shi’ites, to whom Bush had promised support. In effect, the Bush administration had applied the Cold War policy of limited containment in dealing with Hussein. The end of the Cold War and peaceful relations with former adversaries in Moscow and Beijing made possible the largest and most successful U.S. military intervention since the war in Vietnam.

Review & Relate

|

What led to the end of Communist rule in Eastern Europe and the breakup of the Soviet Union? |

How did the end of the Cold War contribute to the growth of globalization? |