Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 936

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 766

George W. Bush and Compassionate Conservatism

In the first presidential election of the new century, the Democratic candidate, Vice President Al Gore, ran against George W. Bush, the Republican governor of Texas and son of the forty-first president. This election marked the first contest between members of the baby boom generation, but in many ways politics remained the same. Candidates began to use the latest technology—the Internet and sophisticated phone banks to mobilize voters—but they rehashed issues stemming from the Clinton years. Gore ran on the coattails of the Clinton prosperity, endorsed affirmative action, was pro-choice on women’s reproductive rights, and warned of the need to protect the environment. Presenting himself as a “compassionate conservative,” Bush opposed abortion, gay rights, and affirmative action while at the same time supporting faith-based reform initiatives in education and social welfare. Also in the race was Ralph Nader, an anticorporate activist who ran under the banner of the Green Party, a party formed in 1991 in support of grassroots democracy, environmentalism, social justice, and gender equality. According to Nader, Gore and Bush were “Tweedledee and Tweedledum—they look and act the same, so it doesn’t matter who you get.” Despite this claim, Nader appealed to much the same constituency as did Gore.

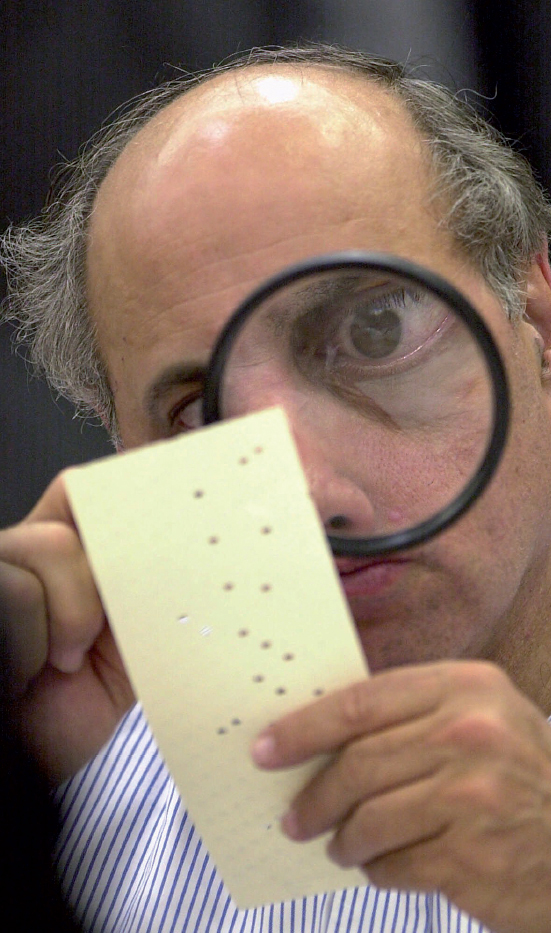

Nader’s candidacy drew votes away from Gore, but fraud and partisanship hurt the Democrats even more. Gore won a narrow plurality of the popular vote (48.4 percent) compared with 47.8 percent for Bush and 2.7 percent for Nader. However, Bush won a slim majority of the electoral votes: 271 to 267. The key state in this Republican victory was Florida, where Bush outpolled Gore by fewer than 500 popular votes. Counties with high proportions of African Americans and the poor encountered the greatest difficulty and outright discrimination in voting, and in these areas voters were more likely to support Gore. A subsequent recount of the vote might have benefited Bush because Republicans controlled the state government. (Jeb Bush, the Republican candidate’s younger brother, was Florida’s governor, and Republicans held a majority in the legislature.) Eventually, litigation over the recount reached the U.S. Supreme Court, and on December 12, 2000, more than a month after the election, the Court proclaimed Bush the winner in a decision that clearly reflected the preferences of the conservative justices appointed by Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush.

George W. Bush did not view his slim, contested victory cautiously. Rather, he intended to appeal mainly to his conservative political base and govern as boldly as if he had received a resounding electoral mandate. Republicans still controlled the House, whereas a Republican defection in the Senate gave the Democrats a one-vote majority. According to the veteran political reporter Ronald Brownstein, Bush and his congressional leaders “would rather pass legislation as close as possible to his preferences on a virtual party-line basis than make concessions to reduce political tensions or broaden his support among Democrats.”

The president promoted the agenda of the evangelical Christian wing of the Republican Party. He spoke out against gay marriage, abortion, and federal support for stem cell research, a scientific procedure that used discarded embryos to find cures for diseases. The president created a special office in the White House to coordinate faith-based initiatives, programs that provided religious institutions with federal funds for social service activities without violating the First Amendment’s separation of church and state.

At the turn of the twenty-first century, a growing number of churchgoers were attending megachurches. These congregations, mainly Protestant, each contained 2,000 or more worshippers and reflected the American impulse for building large-scale organizations, the same passion for size as could be seen in corporate consolidations. Between 1970 and 2005, the number of megachurches jumped from 50 to more than 1,300, with California, Texas, and Florida taking the lead. The establishment of massive churches was part of a worldwide movement, with South Korea home to the largest congregation. Joel Osteen—the evangelical pastor of Lakewood Church in Houston, Texas, the largest megachurch in the United States—drew average weekly audiences of 43,000 people, with sermons available in English and Spanish. Preaching in a former professional basketball arena and using the latest technology, Osteen stood under giant video screens that projected his image. He and other pastors of megachurches have earned enormous wealth from preaching and writing, which their followers consider justified. “Many preachers tell us that God loves us, but Osteen makes us believe that God loves us. And this is why he is so successful,” one observer reflected.

While courting such people of faith, Bush did not neglect economic conservatives. The Republican Congress gave the president tax-cut proposals to sign in 2001 and 2003, measures that favored the wealthiest Americans. Yet to maintain a balanced budget, the cardinal principle of fiscal conservatism, these tax cuts would have required a substantial reduction in spending, which Bush and Congress chose not to do. Furthermore, continued deregulation of business encouraged unsavory and harmful activities that resulted in corporate scandals and risky financial practices.

At the same time, Bush showed the compassionate side of his conservatism. Like Clinton’s cabinet appointments, Bush’s appointments reflected racial, ethnic, and sexual diversity. They included African Americans as secretary of state (Colin Powell), national security adviser (Condoleezza Rice, who later succeeded Powell as secretary of state), and secretary of education (Rod Paige). In addition, the president chose women to head the Departments of Agriculture, Interior, and Labor and also appointed one Latino and two Asian Americans to his cabinet.

In 2002 the president signed the No Child Left Behind Act, which raised federal appropriations for the education of students in primary and secondary schools, especially in underprivileged areas. The law imposed federal criteria for evaluating teachers and school programs, relying on standardized testing to do so. Another display of compassionate conservatism came in the 2003 passage of the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act. The law was projected to cost more than $400 billion over a ten-year period to lower the cost of prescription drugs to some 40 million senior citizens under the 1965 Medicare Act and received support from the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP).