Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 943

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 773

The Great Recession

In 2008 the boom times of the early years of the twenty-first century came to a sudden halt. The stock market’s Dow Jones average, which had hit a high of 14,000, fell 6,000 points, the steepest percentage drop since 1931. Americans who had invested their money in the stock market lost trillions of dollars. The stock market crash plunged investment firms into crisis. Lehman Brothers, a financial services firm founded in 1850, lost more than $2 billion and went bankrupt. The gross domestic product fell by about 6 percent, a loss too great for the economy to absorb quickly. Americans lost their jobs as consumer spending decreased, and many forfeited their homes when they could no longer afford to pay their mortgages. Unemployment jumped from 4.9 percent in January 2008 to 7.6 percent a year later. Confronted by this spiraling disaster, President Bush approved a $700 billion bailout plan to rescue the nation’s largest banks and brokerage houses.

The causes of the Great Recession were many and had developed over a long period. Since the Reagan presidency, the federal government had relaxed regulation of the financial industry. The Clinton administration supported repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act (see chapter 22). This measure, enacted during the New Deal, had separated commercial and investment banking to protect small business people and American families and to avoid the intense financial speculation that preceded the stock market crash of 1929 and the Great Depression. The Federal Reserve Bank encouraged excessive borrowing through keeping interest rates very low and relaxed its oversight of Wall Street practices that placed ordinary investors’ money at risk. Investment houses developed elaborate computer models that produced new and risky kinds of financial instruments, which went unregulated and whose complex nature few people understood. Insurance companies such as American International Group marketed so-called credit default swaps as protection for risky securities, exacerbating the financial crisis. In addition, some financial managers engaged in corrupt practices. One of the most notorious, securities broker Bernard Madoff, swindled investors out of billions of dollars through phony securities dealings.

Consumers also shared some of the blame. Many took advantage of the easy mortgage policies that had been devised to allow buyers to purchase homes beyond their means. Known as subprime mortgages, these loans appealed to borrowers with low incomes or poor credit ratings, especially minorities, who historically had had difficulty obtaining mortgages and personal loans. On the surface, subprime mortgages appeared to make possible the American dream of home ownership. However, when the housing market collapsed, they turned into the nightmare of home foreclosure as many homeowners ended up owing banks and mortgage companies much more than their homes were worth. Investment banks, which had bundled risky mortgages together for speculative purposes, made the situation even worse. Enticed by the easy availability of credit, consumers also went heavily into personal debt to finance purchases of new technology-driven goods, such as personal computers, smartphones, and larger and larger digital televisions.

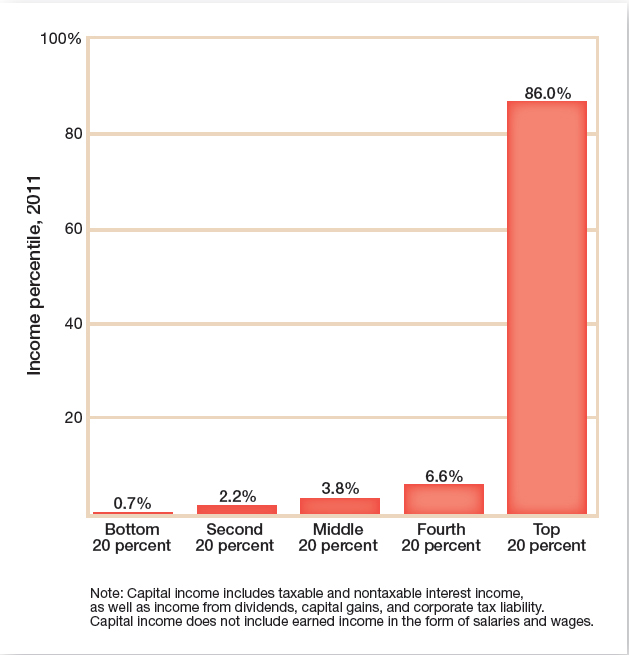

The economy might have experienced a less severe downturn if there had been stricter regulation of the securities industry and greater economic equality to bolster consumer spending. But this was not the case. Wealth remained concentrated in relatively few hands. In 2007 the top 1 percent of households owned 34.6 percent of all privately held wealth, and the next 19 percent held 50.5 percent. Thus 80 percent of Americans owned only 15 percent of the wealth, and the gap between rich and poor widened further. The poverty rate stood at around 13 percent (and as high as 20 percent for those under eighteen years of age). This maldistribution of wealth made it extremely difficult to support an economy that required ever-expanding purchasing power and produced steadily rising personal debt (Figure 29.2).

In the age of globalization, the Great Recession spread rapidly throughout the world. Great Britain’s banking system teetered on the edge of collapse. Some of the other nations in the European Union (EU)—most notably Greece and Spain, which were the most heavily in debt—verged on bankruptcy and had to be rescued by stronger EU nations. Ireland, whose economy had leaped in the early years of the twenty-first century, abruptly fell on hard times. In providing financial assistance to its member states, the EU required countries such as Greece to slash spending for government services and to lower minimum wages. Even in China, where the economy had boomed as a result of globalization, businesses shut down and unemployment rose as consumer demand for its products declined in the wake of worldwide recession.