Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 931

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 760

The Changing American Population

At the same time as the technological revolution helped transform the U.S. economy and society, an influx of immigrants began to greatly alter the composition of the American population. Since passage of the Immigration Act of 1965, the country had experienced a wave of immigration comparable to that at the turn of the twentieth century. As the population of the United States grew from 202 million to 300 million between 1970 and 2006, immigrants accounted for some 28 million of the increase. They came to live in the United States for much the same reasons as those who had journeyed before: to seek economic opportunity and to find political and religious freedom.

Most newcomers who came in the 1980s and 1990s arrived from Latin America and South and East Asia; relatively few Europeans (approximately 2 million) moved to the United States, though their numbers increased after the collapse of the Soviet empire in the early 1990s. Poverty and political unrest pushed migrants out of Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean. The prizewinning film El Norte (1983) dramatized the plight of undocumented Guatemalan Indians who traveled through Mexico to settle in California. Yet most others took advantage of a provision in the 1965 act that permitted them to join family members already settled in the United States. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, Latinos (35 million) had surpassed African Americans (34 million) as the nation’s largest minority group. However, with the arrival of Caribbean and African immigrants, black America was also becoming more diverse in this period.

Explore

See Document 29.1 for one immigrant’s experience in low-wage factory work.

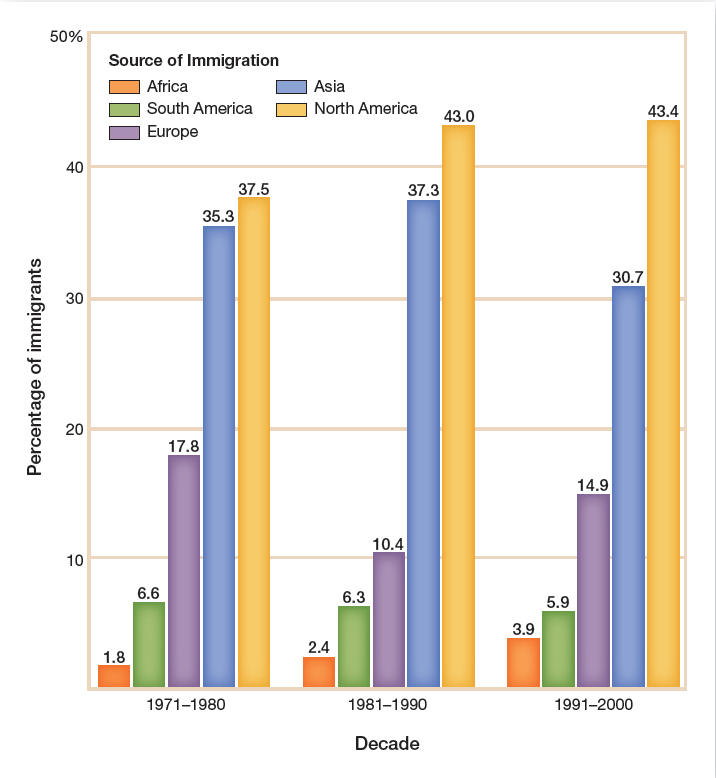

In addition to the 16 million immigrants who came from south of the U.S. border, another 9 million headed eastward from Asian nations, including China, South Korea, and the Philippines, together with refugees from the Vietnam War and Cambodia. By 2007 an estimated 1.6 million Indians from South Asia had immigrated to the United States, most arriving after the 1960s. Indian Americans became the third-largest Asian American group behind Chinese and Filipinos. Another 1 to 2 million people came from predominantly Islamic nations such as Pakistan, Lebanon, Iraq, and Iran (Figure 29.1).

Like their predecessors, new immigrants formed ethnic and religious enclaves. California displayed this fresh face of immigration most vividly. Latinos and Asians had long settled there, and by 2001, 27 percent of the state’s population was foreign-born. The majority of Californians consisted of Latinos, Asian Americans, and African Americans, with whites in the minority. In addition to California and the Southwest, immigrants flocked to northeastern and midwestern cities—New York City, Jersey City, Chicago, and Detroit—as they had in the past. However, they now fanned out through the Southeast, adding to the growing populations of Atlanta, Raleigh-Durham, Charlotte, Columbia, and Memphis and providing these cities with an unprecedented ethnic mixture. Like immigrants before them, they created their own businesses, spoke their own languages, and retained their own religious and cultural practices.

They also encountered hostility from many native-born Americans. Some workers felt threatened by immigrants who took jobs, both commercial and agricultural, at lower wages. Middle-class taxpayers complained that the flood of impoverished immigrants placed the burden on them to fund the social services—schools, welfare, public health—that the newcomers required. Some of the children and grandchildren of immigrants who had assimilated into American culture resented foreigners who pushed for bilingual education and public signs and instructions in their native languages. Immigration critics also complained about the influx of illegal foreign residents among the immigrant population. Besides breaking the law, these critics argued, undocumented immigrants further depressed wages and taxed public resources.

California led the way in rolling back the effects of immigration. In 1986 Californians approved Proposition 63, which declared English to be the state’s official language. Thirty states passed similar laws. In 1994 California voters approved Proposition 186, which prohibited illegal residents from attending public schools and using any social services except emergency health facilities. This proposal never went into effect because federal courts ruled it unconstitutional. Also, some conservative Republicans like President Ronald Reagan, former governor of California, along with agribusiness and other corporate interests that relied on cheap immigrant labor to keep their operating costs low, opposed such severe measures.

Review & Relate

|

How have computers changed life in the United States? |

How has globalization affected business consolidation and immigration? |