Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 78

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 69

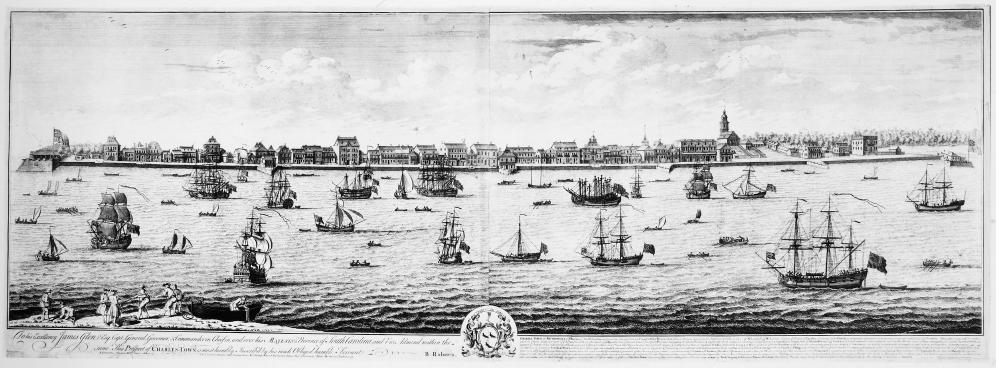

Seaport Cities and Consumer Cultures

The same trade in human cargo that brought misery to millions of Africans provided traders, investors, and plantation owners with huge profits that helped turn America’s seaport cities into centers of culture and consumption. When Eliza Lucas arrived in Charleston in 1738, she noted that “the Metropolis is a neat pretty place. The inhabitants [are] polite and live in a very gentile [genteel] manner.” Throughout British North America, seaports, with their elegant homes, fine shops, and lively social seasons, captured the most dynamic aspects of colonial life. Although cities like New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Charleston contained less than 10 percent of the colonial population, they served as focal points of economic, political, social, and cultural activity.

Many affluent urban families shed the religious strictures or financial constraints that shaped the lives of their colonial forebearers and created a consumer revolution in North America. Changing patterns of consumption challenged traditional definitions of status. Less tied to birth and family pedigree, status in the colonies became more closely linked to financial success and a genteel lifestyle. Successful men of humble origins and even those of Dutch, Scottish, French, and Jewish heritage might join the British-dominated colonial gentry.

Of those who made the leap in the early eighteenth century, Benjamin Franklin was the most notable. He might have taken the path of the “infortunate” William Moraley Jr., but Franklin was apprenticed to his brother, a printer, an occupation that matched his interest in books, reading, and politics. At age sixteen, Franklin published (anonymously) his first essays in his brother’s paper, the New England Courant. Two years later, a family dispute led Franklin to try his luck in New York and then Philadelphia. His fortunes were fragile, but hard work, a quick wit, good luck, and political connections led to success. In 1729 Franklin purchased the Pennsylvania Gazette and became the colony’s official printer.

While Franklin worried about the concentration of wealth in too few hands, most colonial elites happily displayed their profits. Thus in the early eighteenth century, leading merchants in Boston, Salem, New York, and Philadelphia emulated British styles and built fine two- and three-story brick homes that had separate rooms for sleeping, eating, and entertaining guests. Mercantile elites also redesigned the urban landscape in the early eighteenth century. They donated money for brick churches and stately town halls. They constructed new roads, wharves, and warehouses to facilitate trade, and they invested in bowling greens and public gardens that beckoned affluent families on a Sunday afternoon.

Many Anglo-American elites used their knowledge of London fashions to reassert their British identity. Tea drinking was especially important in this regard, and families who could afford the finest furnishings and the time for extended social rituals made teatime a daily event. Yet the tea served at the home of Boston merchant Anthony Stoddard was imported from East Asia; the cups, saucers, and teapot were from China; and a handsome bowl held sugar from the West Indies. Stoddard decorated his home with heavily lacquered “japanned” boxes, French-patterned wallpaper, Indian calico bedding, and Italian silk curtains—all of which demonstrated that he was a successful merchant as well as a fashionable British citizen.

The spread of international commerce created a lively cultural life and great affluence in colonial cities. But it also created deep divisions between rich and poor. Wealthy merchants and professionals congregated in urban areas along with a middling group of artisans and shopkeepers and a growing class of unskilled laborers, widows, orphans, the elderly, the disabled, and the unemployed. The frequent wars of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries contributed to these divisions by boosting the profits of merchants, shipbuilders, and artisans. They also improved the wages of seamen temporarily. But in their aftermath, rising prices, falling wages, and a lack of jobs led to the concentration of wealth in fewer hands.

Review & Relate

|

What place did North American colonists occupy in the eighteenth-century global trade network? |

How did the British government seek to maintain control over the colonial economy and ensure that its colonies served Britain’s economic and political interests? |