Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 81

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 71

Finding Work in the Colonies

The demand for labor did not necessarily help free laborers find work. Many employers preferred indentured servants, apprentices, or others who came cheap and were bound by contract. Others employed criminals or purchased slaves, who would provide years of service for a set price. Free laborers who sought a decent wage and steady employment needed to match their desire to work with skills that were in demand.

When William Moraley ended his indenture and sought work, he discovered that far fewer colonists than Englishmen owned timepieces, leaving him without a useful trade. So he tramped the countryside, selling his labor when he could, but found no consistent employment. Returning to New York and Philadelphia, William begged lodging from friends, considered marrying an elderly widow, was imprisoned for minor offenses, and accepted Quaker charity. But he fell ever deeper in debt. Thousands of other men and women, most without Moraley’s education or skills, also found themselves at the mercy of unrelenting economic forces.

Many poor men and women found jobs building homes, loading ships, or spinning yarn. But they were usually employed for only a few months a year. The rest of the time they scrounged for bread and beer, begged in the streets, or stole what they needed. Most lived in ramshackle buildings filled with cramped and unsanitary rooms. Freezing in winter and sweltering in summer, these quarters served as breeding grounds for smallpox, scarlet fever, and other diseases. Children born into such squalid circumstances were lucky to survive their first year. Those who survived could watch ships sail into port and earn a few pence running errands for captains or sailors, but they would never have access to the bounteous goods intended for those who lived in stately mansions.

By the early eighteenth century, older systems of labor, like indentured servitude, began to decline in many areas. In some parts of the North and across the South, white servants were gradually replaced by African slaves. At the same time, farm families who could not usefully employ all their children began to bind out sons and daughters to more prosperous neighbors. Apprentices, too, competed for positions. Unlike most servants, apprentices contracted to learn a trade. They trained under the supervision of a craftsman, who gained cheap labor by promising to teach a young man (and most apprentices were men) his trade. But master craftsmen limited the number of apprentices they accepted to maintain the value of their skills.

Another category of laborers emerged in the 1720s. A population explosion in Europe and the rising price of wheat and other items convinced many people to seek passage to America. Shipping agents offered them loans that were repaid when the immigrants found a colonial employer who would redeem (that is, repay) the original loan. In turn, these redemptioners labored for the employer for a set number of years, though they could live independently with their own family. The redemption system was popular in the Middle Atlantic colonies, especially among German immigrants who hoped to establish farms on the Pennsylvania frontier. While many succeeded, their circumstances could be extremely difficult.

Explore

Read two immigrants’ descriptions of their varying experiences in Documents 3.4 and 3.5.

Large numbers of convicts, too, entered the British colonies in the eighteenth century. Jailers in charge of Britain’s overcrowded prisons offered inmates the option of transportation to the colonies. Hundreds were thus bound out each year to American employers. The combination of indentured servants, redemptioners, apprentices, and convicts ensured that as late as 1750 the majority of white workers—men and women—were bound to some sort of contract.

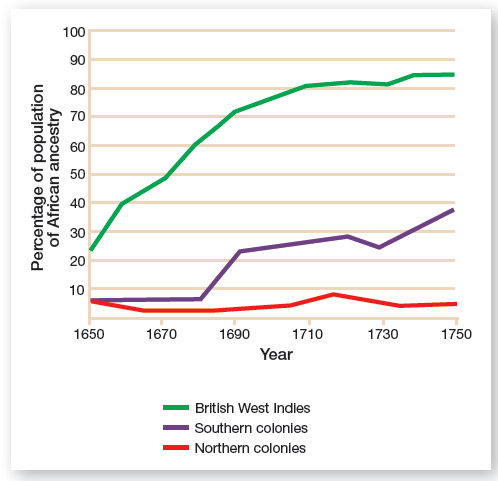

Sometimes white urban workers also competed with slaves, especially in the northern colonies. Africans and African Americans formed only a small percentage of the northern population, just 5 percent from Pennsylvania to New Hampshire in 1750. In the colony of New York, however, blacks formed about 14 percent of inhabitants. While some enslaved blacks worked on agricultural estates in the Hudson River valley and New Jersey, even more labored as household servants, dockworkers, seamen, and blacksmiths in New York City alongside British colonists and European immigrants (Figure 3.2). Considered a status symbol by many wealthy merchants, urban slaves were usually discouraged from marrying or bearing large numbers of children. However, some masters allowed their slaves to marry and set up independent households or to hire themselves out to other employers, as long as their wages were paid to their owners.