Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 85

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 75

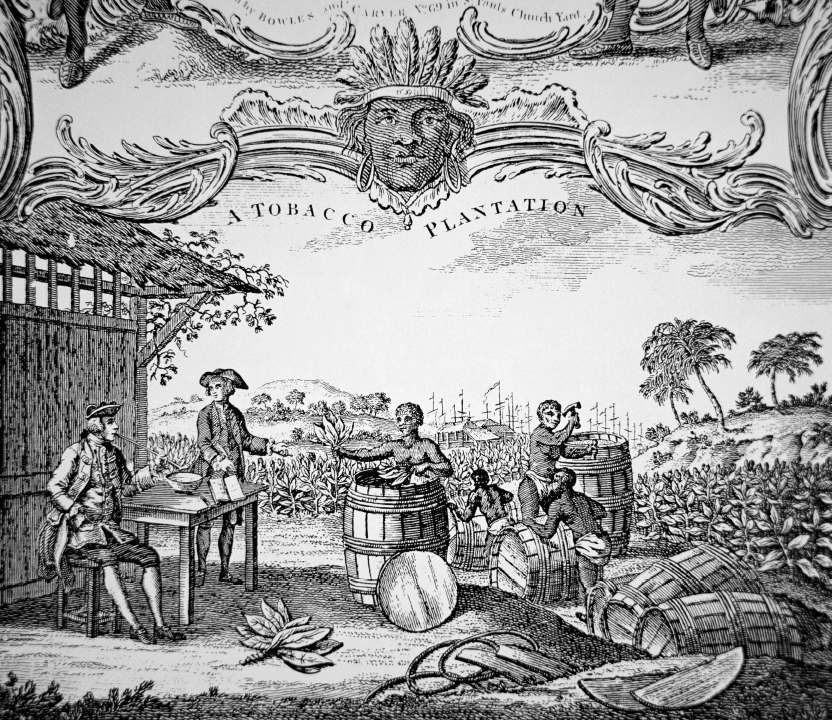

Slavery Takes Hold in the South

The rise of slavery reshaped the South in numerous ways. The shift from white indentured servants to black slaves began in Virginia after 1676 (see chapter 2) and soon spread across the Chesapeake. The Carolinas, meanwhile, developed as a slave society from the start. Slavery in turn allowed for the expanded cultivation of cash crops like tobacco, rice, and indigo, which promised high profits for planters as well as merchants. But these developments also made southern elites more dependent on the global market and limited opportunities for poorer whites and all blacks. They also ensured that Indians and many whites were pushed farther west as planters sought more land for their ventures.

In the 1660s, the Virginia Assembly passed a series of laws that made slavery a status inherited through the mother, denied that the status could be changed by converting to Christianity, and granted masters the right to kill slaves who resisted their authority (see chapter 2). In 1680 the Assembly made it illegal for “any negro or other slave to carry or arme himself with any club, staffe, gunn, sword, or any other weapon of defence or offence.” Nor could slaves leave their master’s premises without a certificate of permission. Those who disobeyed were whipped or branded. Increasingly harsh laws in Virginia and Maryland, modeled on those in Barbados, coincided with a rise in the number of slaves imported to the colony. The statutes also ensured the decline of the free black population in the Chesapeake. In 1668 one-third of all Africans and African Americans in Virginia and Maryland were still free, but the numbers dwindled year by year. Once the Royal African Company started supplying the Chesapeake with slaves directly from Africa in the 1680s, the pace of change quickened. By 1750, 150,000 blacks resided in the Chesapeake, and only about 5 percent remained free.

Direct importation from Africa had other negative consequences on slave life. Far more men than women were imported, skewing the sex ratio in a population that was just beginning to form families and communities. Women like men performed heavy field work, and few bore more than one or two children. When these conditions sparked resistance by the enslaved, fearful whites imposed even stricter regulations. In 1705 the Virginia Assembly passed an omnibus “Negro Act” that incorporated earlier provisions and made absolutely clear the special legal status of the enslaved. For instance, while mistreated white servants could sue in court, black slaves could not. And a slave who ran away and was captured could be tortured and dismembered in hopes of “terrifying others from the like practices.”

While slavery in the Carolinas was influenced by developments in the Chesapeake, it was shaped even more directly by practices in the British West Indies. Many wealthy families from Barbados, Antigua, and other sugar islands—including that of Colonel Lucas—established plantations in the Carolinas. At first, they brought slaves from the West Indies to oversee cattle and pigs and assist in the slaughter of livestock and curing of meat for shipment back to the West Indies. Some of the slaves grew rice, using techniques learned in West Africa, to supplement their diet. Owners soon realized that rice might prove very profitable. Although not widely eaten in Europe, rice could provide cheap and nutritious food for sailors, orphans, convicts, and peasants. Relying initially on Africans’ knowledge, planters began cultivating rice for export.

The need for African rice-growing skills and the fear of attacks by Spaniards and Indians led Carolina owners to grant slaves rights unheard of in the Chesapeake or the West Indies. Initially slaves were allowed to carry guns and serve in the militia. For those who nonetheless ran for freedom, Spanish and Indian territories offered refuge. Still, most stayed, depending for support on bonds they had developed in the West Indies. The frequent absence of owners also offered Carolina slaves greater autonomy.

As rice cultivation expanded, however, slavery in the Carolinas turned more brutal. The Assembly enacted harsher and harsher slave codes to ensure control of the growing labor force. No longer could slaves carry guns, join militias, meet in groups, or travel without a pass. As planters began to import more slaves directly from Africa, sex ratios, already male dominated, became even more heavily skewed. In addition, older community networks from the West Indies were disrupted. Military patrols by whites were initiated to enforce laws and labor practices. Some plantations along the Carolina coast turned into virtual labor camps, where thousands of slaves worked under harsh conditions with no hope of improvement.

By 1720 blacks outnumbered whites in the Carolinas, and fears of slave rebellions inspired South Carolina officials to impose even harsher laws and more brutal enforcement measures. When indigo joined rice as a cash crop in the 1740s, the demand for slave labor increased further. Although far fewer slaves—about 40,000 by 1750—resided in South Carolina than in the Chesapeake, they constituted more than 60 percent of the colony’s total population.