Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 105

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 88

Reproduction and Women’s Roles

Maintaining a farm required the work of both women and men, which made marriage an economic as well as a social and religious institution. In the early eighteenth century, more than 90 percent of white women married. And as mortality declined in the South and remained low in the North, most wives spent the first twenty years of marriage bearing and rearing children. By 1700 a New England wife who married at age twenty and survived to forty-five bore an average of eight children, most of whom lived to adulthood. In the Chesapeake, where mortality rates remained higher and the sex ratio still favored men, marriage and birth rates were slightly lower and infant mortality higher. Still, by the 1720s, southern white women nearly matched the reproductive rates of their northern counterparts.

Fertility rates among enslaved Africans and African Americans were much lower than those among whites in the early eighteenth century, and fewer infants survived to adulthood. It was not until the 1740s that the majority of slaves were born in the colonies rather than imported. But slowly some slave owners began to realize that encouraging reproduction made good economic sense. Still, enslaved women, most of whom worked in the fields, gained only minimal relief from their labors during pregnancy. Female slaves who lived in seaport cities were more likely to work in homes or shops, a healthier environment than the fields. But owners in already-crowded urban households often discouraged marriage and childbearing.

Immigrants from Scotland, Ireland, and Europe, many of whom lived in the Middle Atlantic colonies, often bore large numbers of children. Quakers, German Mennonites, Scots-Irish Presbyterians, and other groups flowed into New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware. Some settled in New York City and Philadelphia, but even more spread into rural areas, filling the interior of New Jersey and populating the Pennsylvania frontier. As they pushed westward, growing families replicated the experiences of early colonists, depending on their own resources and those of their immediate neighbors to carve farms and communities out of the wilderness.

Wherever they settled, mothers combined childbearing and child rearing with a great deal of other work. While some affluent families could afford wet nurses and nannies, most colonial women fended for themselves or hired temporary help for particular tasks. Mothers with babies on hip and children under foot hauled water, fed chickens, collected eggs, picked vegetables, prepared meals, spun thread, and manufactured soap and candles. Children were at constant risk of disease and injury, but physicians were rare in many rural areas. Still, farm families were spared from the overcrowding, raw sewage, and foul water that marked most urban neighborhoods.

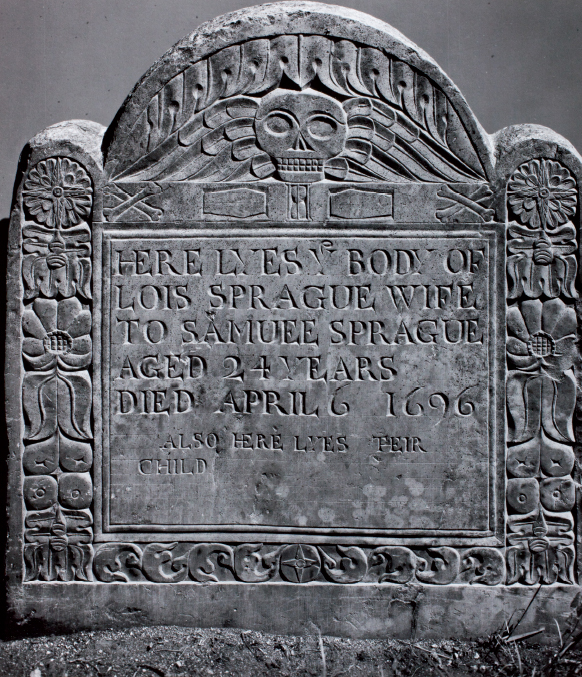

Colonists feared the deaths of mothers as well as of infants. In 1700 roughly one out of thirty births ended in the mother’s death. Women who bore six to eight children thus faced death on a regular basis. Many prayed intensely before and during labor, hoping to survive the ordeal. One minister urged pregnant women to prepare their souls, claiming, “For ought you to know your Death has entered into you.”

When a mother died when her children were still young, her husband was likely to remarry soon afterward in order to maintain the family and his farm or business. Even though fathers held legal guardianship over their children, there was little doubt that child rearing, especially for young children and for daughters, was women’s work. Many husbands acknowledged this role, prayed for their wife while in labor, and sought to ease her domestic burdens near the end of a pregnancy. But some women received only hostility and abuse from their husbands. In these cases, wives and mothers had few means to protect their children or themselves.