Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 106

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 90

The Limits of Patriarchal Order

Sermons against fornication; ads for runaway spouses, servants, and slaves; reports of domestic violence; poems about domineering wives; petitions for divorce; and legal suits charging rape, seduction, or breach of contract—all of these make clear that ideals of patriarchal authority did not always match the reality. It is impossible to quantify precisely the frequency with which women experienced or resisted abuse at the hands of men. Still, a variety of evidence points to increasing tensions in the early eighteenth century around issues of control—by husbands over wives, fathers over children, and men over women.

Women’s claims about men’s misbehavior were often demeaned as gossip, but gossip could be an important weapon for those who had little chance of legal redress. In colonial communities, credit and thus trust were central to networks of exchange, so damaging a man’s reputation could be a serious matter. Still, gossip was not as powerful as legal sanctions. Thus in cases in which a woman bore an illegitimate child, suffered physical and sexual abuse, or was left penniless by a husband who drank and gambled, she or her family might seek assistance from the courts.

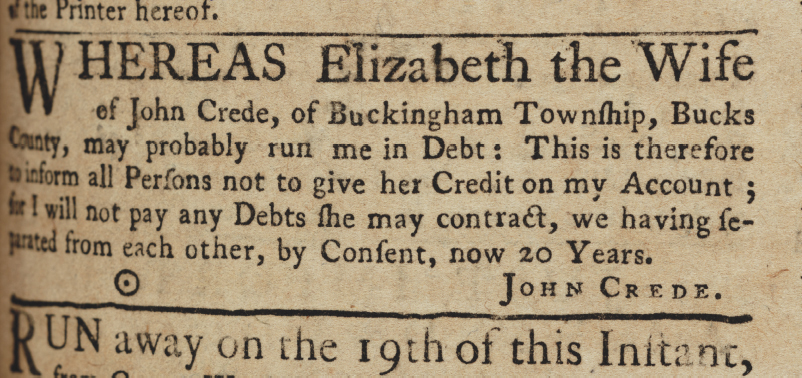

Divorce was as rare in the colonies as it was in England. In New England, colonial law allowed for divorce, but few were granted and almost none to women before 1750. In other colonies, divorce could be obtained only by an act of the colonial assembly and was therefore confined to the wealthy and powerful. If a divorce was granted, the wife usually received “maintenance,” an allowance that provided her with funds to feed and clothe herself. Yet without independent financial resources, she nearly always had to live with relatives. Custody of any children was awarded to the father because he had the economic means to support them, although infants or young girls might be assigned to live with the mother. Some couples were granted a separation of bed and board, which meant they lived apart but could not remarry. Here, too, the wife remained dependent on her estranged husband or on family members for economic support. A quicker and cheaper means of ending an unsatisfactory marriage was to abandon one’s spouse. Again wives were at a disadvantage since they had few means to support themselves or their children. Colonial divorce petitions citing desertion and newspaper ads for runaway spouses suggest that husbands fled in at least two-thirds of such cases.

In the rare instances when women did obtain a divorce, they had to bring multiple charges against their husband. Domestic violence, adultery, or abandonment alone was insufficient to gain redress. Indeed, ministers and relatives were likely to counsel abused wives to change their behavior or suffer in silence since by Scripture and law a wife was subject to her husband’s will. Even evidence of brutal assaults on a wife rarely led to legal redress. Because husbands had the legal right to “correct” their wives and children and because physical punishment was widely accepted, it was difficult to distinguish between “correction” and abuse.

Single women also faced barriers in seeking legal redress. By the late seventeenth century, church and civil courts in New England gave up on coercing sexually active couples to marry. Judges, however, continued to hear complaints of seduction or breach of contract brought by the fathers of single women who were pregnant but unmarried. Had Sarah Grosvenor survived the abortion, her family could have sued Amasa Sessions on the grounds that he gained “carnal knowledge” of her through “promises of marriage.” If the plaintiffs won, the result was no longer marriage, however, but financial support for the child. In 1730 the Court of Common Pleas in Concord, Massachusetts, heard testimony from Susanna Holding that a local farmer, Joseph Bright, who was accused of fathering her illegitimate child, had “ruined her Reputation and Fortunes.” When Bright protested his innocence, Holding found townsmen to testify that the farmer, “in his courting of her . . . had designed to make her his Wife.” In this case, the abandoned mother mobilized members of the community, including men, to uphold popular understandings of patriarchal responsibilities. Without such support, women were less likely to win their case. Still, towns were eager to make errant men support their offspring so that the children did not become a public burden. And at least in Connecticut, a growing number of women initiated civil suits from 1740 on, demanding that men face their financial and moral obligations.

Women who were raped faced even greater legal obstacles than those who were seduced and abandoned. In most colonies, rape was a capital crime, punishable by death, and all-male juries were reluctant to find men guilty. In addition, men were assumed to be the aggressor in sexual encounters. Although bawdy women were certainly a part of colonial lore, it was assumed that most women needed persuading to engage in sex. Precisely when persuasion turned to coercion was less clear. Unlikely to win and fearing humiliation in court, few women charged men with rape. Yet more did so than the records might show since judges and justices of the peace sometimes downgraded rape charges to simple assault or fornication, that is, sex outside of marriage (Table 4.2).

| Date | Defendant/Victim | Charge on Indictment in Testimony | Charge in Docket |

| 1731 | Lawrence MacGinnis/Alice Yarnal | Assault with attempt to rape | None |

| 1731 | Thomas Culling/Martha Claypool | Assault with attempt to rape | Assault |

| 1734 | Abraham Richardson/Mary Smith | Attempted rape | Assault |

| 1734 | Thomas Beckett/Mindwell Fulfourd | Theft (testimony of attempted rape) | Theft |

| 1734 | Unknown/Christeen Pauper | (Fornication charge against Christeen) | None |

| 1735 | Daniel Patterson/Hannah Tanner | Violent assault to ravish | Assault |

| 1736 | James White/Hannah McCradle | Attempted rape/adultery | Assault |

| 1737 | Robert Mills/Catherine Parry | Rape | None |

| 1738 | John West/Isabella Gibson | Attempt to ravish/assault | Fornication |

| 1739 | Thomas Halladay/Mary Mouks | Assault with intent to ravish | None |

Source: Sharon Block, Rape and Sexual Power in Early America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press). Data from Chester County Quarter Sessions Docket Books and File Papers, 1730–1739.

White women from respectable families had the best chance of gaining support from local authorities, courts, and neighbors when faced with seduction, breach of contract, or rape. Yet such support depended on young people confiding in their elders. By the mid-eighteenth century, however, children were seeking more control over their sexual behavior and marriage prospects, and certain behaviors—for example, sons settling in towns distant from the parental home, younger daughters marrying before their older sisters, and single women finding themselves pregnant—increased noticeably. In part, these trends were natural consequences of colonial growth and mobility. The bonds that once held families and communities together began to loosen. But in the process, young women’s chances of protecting themselves against errant men diminished. Just as important, even when they faced desperate situations, young women like Sarah Grosvenor increasingly turned to sisters and friends rather than fathers or ministers.

If women in respectable families found it difficult to redress abuse from suitors or husbands, the poor and those who labored as servants or slaves had even fewer options. Slaves in particular had little hope of prevailing against brutal owners. Even servants faced tremendous obstacles in obtaining legal independence from masters or mistresses who beat or sexually assaulted them. Colonial judges and juries generally refused to declare a man who was wealthy enough to support servants guilty of criminal acts against them. Moreover, female servants and slaves were regularly depicted in popular culture as lusty and immoral, making it even less likely that they would gain the sympathy of white male judges or juries. Thus for most servants and slaves, running away was their sole hope for escape from abuse; however, if they were caught, their situation would likely worsen. Even poor whites who lived independently had little chance of addressing issues of domestic violence, seduction, or rape through the courts. For unhappy couples beyond the help or reach of the law, abandonment was no doubt the most likely option. And as the colonies grew and diversified, leaving a wife and children or an abusive husband or master behind may have become a bit easier than it was in the small and isolated communities of earlier periods.

Review & Relate

|

Why and how did the legal and economic status of colonial women decline between 1650 and 1750? |

How did patriarchal ideals of family and community shape life and work in colonial America? What happened when men failed to live up to those ideals? |