Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 112

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 98

The Roots of the Great Awakening

The European religious landscape had grown remarkably more diverse in the two hundred years following the Reformation as Presbyterians, Lutherans, Methodists, Baptists, Quakers, and a variety of smaller sects competed for followers. Another current also had an impact: By the eighteenth century, the Enlightenment, a cultural movement that emphasized rational and scientific thinking over traditional religion and superstition, had taken root, particularly among elites. As North American colonies attracted settlers from new denominations and as more and more colonists were influenced by Enlightenment thought, the colonists as a whole became more accepting of religious diversity.

There were, however, countervailing forces. The German Pietists in particular challenged Enlightenment ideas that had influenced many Congregational and Anglican leaders in Europe and the colonies. Pietists not only decried the power of established churches but also urged individuals to follow their heart rather than their head in spiritual matters. Only by restoring intensity and emotion to worship, they believed, could spiritual life be revived. Persecuted in Germany, Pietists migrated to Great Britain and North America, where their ideas influenced Scots-Irish Presbyterians, French Huguenots, and members of the Church of England. John Wesley, the founder of Methodism and a professor of theology at Oxford University, taught Pietist ideas to his students. George Whitefield was inspired by Wesley. Like the German Pietists whose ideas he embraced, Whitefield believed that the North American colonies offered an important opportunity to implement these ideas.

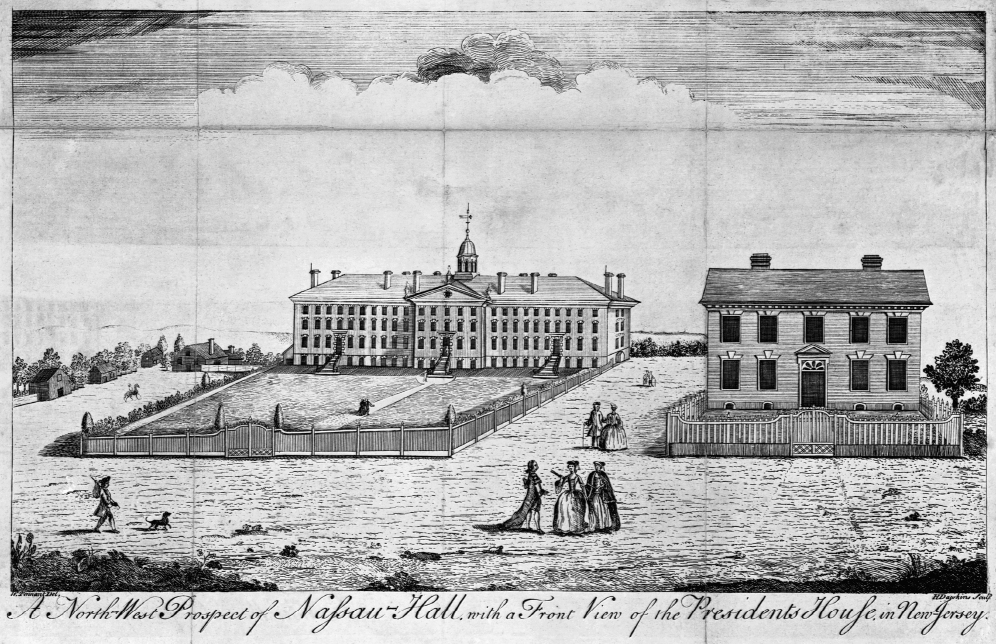

But not all colonists waited for Whitefield or the German Pietists to rethink their religious commitments. By 1700 both laymen and ministers voiced growing concern with the state of colonial religion. Preachers educated in England or at the few colleges established in the colonies, like Harvard College (1636) and the College of William and Mary (1693), often emphasized learned discourse over passion. At the same time, there were too few clergy to meet the demands of the rapidly growing population in North America. Many rural parishes covered vast areas, and residents grew discouraged at the lack of ministerial attention. Meanwhile urban churches increasingly reflected the class divisions of the larger society. In many meetinghouses, wealthier members paid substantial rents to seat their families in the front pews. Small farmers and shopkeepers rented the cheaper pews in the middle of the church, while the poorest congregants—including landless laborers, servants, and slaves—sat on free benches at the very back or in the gallery. Educated clergy might impress the richest parishioners with their learned sermons, but they did little to move the spirits of the congregation at large.

In 1719 the Reverend Theodorus Freylinghuysen, a Dutch Reformed minister in New Brunswick, New Jersey, began emphasizing parishioners’ emotional investment in Christ. The Reverend William Tennent arrived in neighboring Pennsylvania with his family about the same time. He despaired that Presbyterian ministers were too few in number to reach the growing population and, like Freylinghuysen, feared that their approach was too didactic and cold. Tennent soon established his own academy—one room in a log cabin—to train his four sons and other young men for the ministry. Though disparaged by Presbyterian authorities, the school attracted devout students. A decade later, in 1734–1735, Jonathan Edwards, a Congregational minister in Northampton, Massachusetts, made clear the value of religious appeals that emphasized emotion over logic. Proclaiming that “our people do not so much need to have their heads stored [with knowledge] as to have their hearts touched,” he initiated a local revival that reached hundreds of colonists.

Like Edwards, William Tennent’s son Gilbert urged colonists to embrace “a true living faith in Jesus Christ.” Assigned a church in New Brunswick in 1726, Tennent met Freylinghuysen, who viewed conversion as a three-step process: Individuals must be convinced of their sinful nature, experience a spiritual rebirth, and then behave piously as evidence of their conversion. Tennent embraced these measures, believing they could lance the “boil” of an unsaved heart and apply the “balsam” of grace and righteousness. Then in 1739 Tennent met Whitefield, who launched a wave of revivals that revitalized and transformed religion across the colonies.