Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 144

Documents 5.2 and 5.3

Protesting the Stamp Act: Two Views

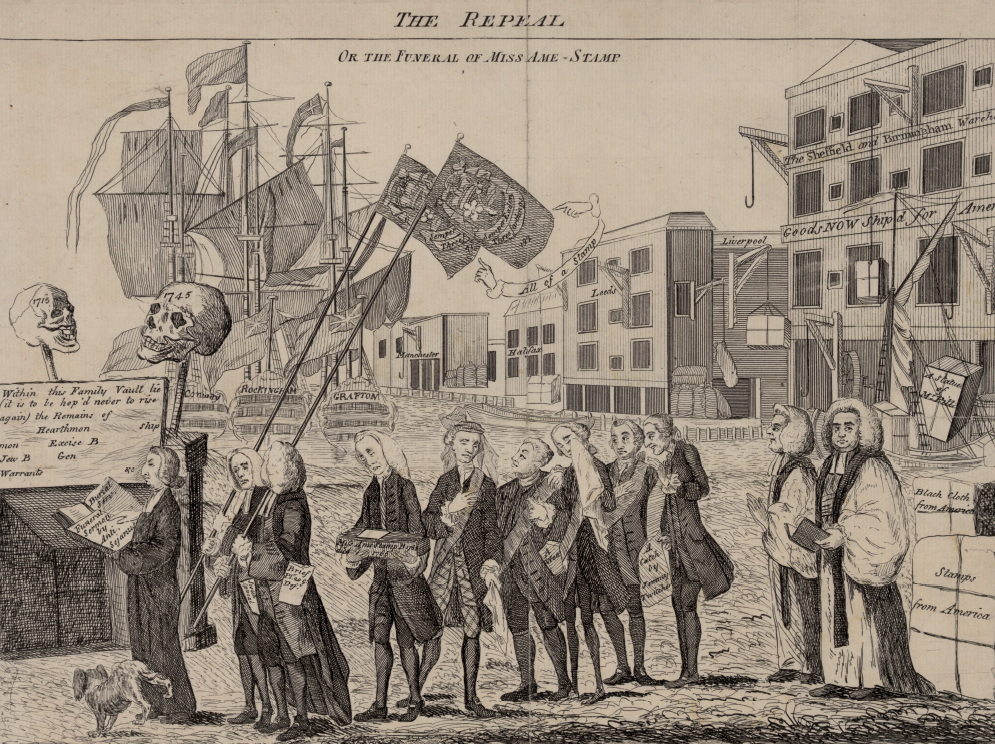

The announcement of the Stamp Act in 1764 ignited widespread protests throughout the colonies. Colonial governments petitioned Parliament for its repeal, crowds attacked stamp agents and distributors, broadsides and newspapers denounced “taxation without representation,” and boycotts and mass demonstrations were organized in major cities, some of which turned violent. Protests were not limited to the colonists, however, as shown in the petition to Parliament from London merchants, who argued that they were losing revenue because of colonial boycotts of British goods. The second document celebrates the repeal of the Stamp Act by depicting a funeral for the act led by its supporters. Dr. William Scott, who published letters supporting the Stamp Act in a London newspaper, leads the procession.

Explore

| 5.2 | London Merchants Petition to Repeal the Stamp Act, 1766 |

And that, in consequence of the trade between the colonies and the mother country, as established and permitted for many years, and of the experience which the petitioners have had of the readiness of the Americans to make their just remittances to the utmost of their real ability, they have been induced to make and venture such large exportations of British manufactures, as to leave the colonies indebted to the merchants of Great Britain in the sum of several millions sterling; at that at this time the colonists, when pressed for payment, appeal to past experience, in proof of their willingness; but declare it is not in their power, at present, to make good their engagements, alleging, that the taxes and restrictions laid upon them, and the extension of the jurisdiction of vice admiralty courts established by some late acts of parliament, particularly . . . by an act passed in the fifth year of his present Majesty, for granting and applying certain stamp duties, and other duties, in the British colonies and plantations in America, with several regulations and restraints, which, if founded in acts of parliament for defined purposes, are represented to have been extended in such a manner as to disturb legal commerce and harass the fair trader, have so far interrupted the usual and former most fruitful branches of their commerce, restrained the sale of their produce, thrown the state of the several provinces into confusion, and brought on so great a number of actual bankruptcies, that the former opportunities and means of remittances and payments are utterly lost and taken from them; and that the petitioners are, by these unhappy events, reduced to the necessity of applying to the House, in order to secure themselves and their families from impending ruin; to prevent a multitude of manufacturers from becoming a burthen to the community, or else seeking their bread in other countries, to the irretrievable loss of this kingdom; and to preserve the strength of this nation entire.

Source: Guy Steven Callender, Selections from the Economic History of the United States, 1765–1860 (Boston: Ginn, 1909), 146–47.

Explore

| 5.3 | The Repeal, 1766 |

Interpret the Evidence

Question

How do both the petition and the cartoon emphasize the economic arguments against the Stamp Act? What role, if any, do arguments about political representation play in these documents?

Question

Who do you think was the intended audience for each of these documents? What evidence can you find in each document to support your answer?

Put It in Context

Question

What do these documents suggest about the more general relations among the colonies, British merchants, and Parliament in 1766?