Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 146

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 128

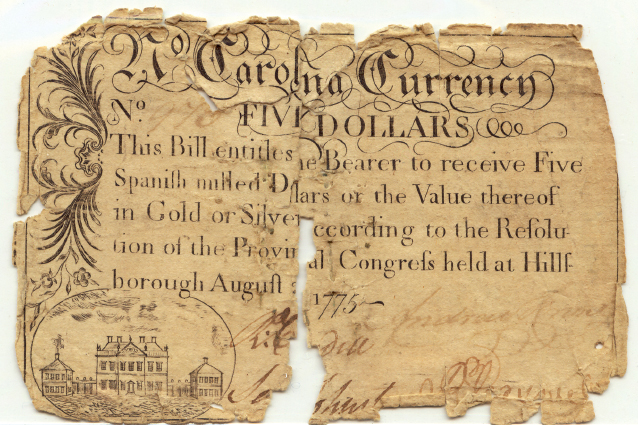

Continuing Conflicts at Home

As colonists in Boston and other seaport cities rallied to protest British taxation, other residents of the thirteen colonies continued to challenge authorities closer to home. In the same years as the Stamp Act and Townshend Act protests, tenants in New Jersey and the Hudson valley continued their campaign for economic justice. So, too, did Herman Husband and the Sandy Creek Association. Governor Tryon of North Carolina had been among those who claimed that Parliament had abused its power in taxing the colonies, but he did not recognize such abuses in his own colony. Instead, he viewed the Regulators, formed during the campaign against the Townshend Act, as traitors. The Regulators, however, insisted that they were simply trying to protect farmers and laborers from deceitful speculators, corrupt politicians, and greedy employers. A year after the Boston Massacre, Governor Tryon sent troops to quell what he viewed as open rebellion on the Carolina frontier. The Regulators amassed two thousand farmers to defend themselves, although Husband, a pacifist, was not among them. But when twenty Regulators were killed and more than a hundred wounded at the Battle of Alamance Creek in May 1771, he surely knew many of the fallen. Six Regulators were hanged a month later in front of Governor Tryon, local officials, and hundreds of neighboring farm families. Although North Carolina Regulators did not proclaim this the Alamance Massacre, many local residents harbored deep resentments against colonial officials for what they viewed as the slaughter of honest, hardworking men. Herman Husband fled the Carolina frontier and headed north.

Resentments against colonial leaders were not confined to North Carolina. An independent Regulator movement emerged in South Carolina in 1767. Far more effective than their North Carolina counterparts, South Carolina Regulators seized control of the western regions of the colony, took up arms, and established their own system of frontier justice. By 1769 the South Carolina Assembly negotiated a settlement with the Regulators, establishing new parishes in the colony’s interior that ensured greater representation for frontier areas and extending colonial political institutions, such as courts and sheriffs, to the region.