Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 131

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 112

The Opening Battles

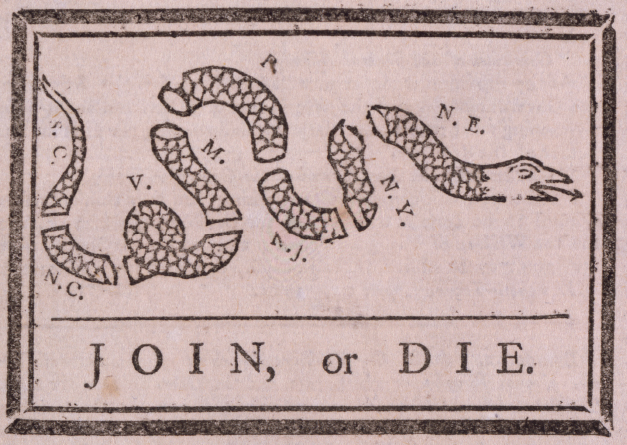

Even before Washington and his troops were defeated in July 1754, the British sought to protect the colonies against threats from the French and the Indians. To limit such threats, the British were especially interested in cementing an alliance with the powerful Iroquois Confederacy, composed of six northeastern tribes. Thus the British invited an official delegation from the Iroquois to a meeting in June 1754 in Albany, New York, with representatives from the New England colonies, New York, Pennsylvania, and Maryland. Benjamin Franklin of Philadelphia had drawn up a Plan of Union that would establish a council of representatives from the various colonial assemblies to debate issues of frontier defense, trade, and territorial expansion and to recommend terms mutually agreeable to colonists and Indians. Their deliberations were to be overseen by a president-general appointed and supported by the British crown.

The Albany Congress created new bonds among a small circle of colonial leaders, but it failed to establish a firmer alliance with the Iroquois or resolve problems of colonial governance. The British government worried that the proposed council would prove too powerful, undermining the authority of the royal government. At the same time, the individual colonies were unwilling to give up any of their autonomy in military, trade, and political matters to some centralized body. Moreover, excluded from Franklin’s Plan of Union, the Iroquois delegates at the Albany Congress broke off talks with the British in early July. The Iroquois became more suspicious and resentful when colonial land agents and fur traders used the Albany meeting as an opportunity to make side deals with individual Indian leaders.

Yet if war was going to erupt between the British and the French, the Iroquois and other Indian tribes could not afford to have the outcome decided by imperial powers alone. For most Indians, contests among European nations for land and power offered them the best chance of survival in the eighteenth century. They gained leverage as long as various imperial powers needed their trade items, military support, and political alliances. This leverage would be far more limited if one European nation controlled most of North America.

The various Indian tribes adopted different strategies. The Delaware, Huron, Miami, and Shawnee nations, for example, allied themselves with the French, hoping that a French victory would stop the far more numerous British colonists from invading their settlements in the Ohio valley. Members of the Iroquois Confederacy, on the other hand, tried to play one power against the other, hoping to win concessions from the British in return for their military support. The Creek, Choctaw, and Cherokee nations also sought to perpetuate the existing stalemate among European powers by bargaining alternately with the British in Georgia and the Carolinas, the French in Louisiana, and the Spaniards in Florida.

Faced with incursions into their lands, some Indian tribes launched preemptive attacks on colonial settlements. Along the northern border of Massachusetts, for example, in present-day New Hampshire, Abenaki Indians attacked British settlements in August 1754, taking settlers captive and marching them north to Canada. There they traded them to the French, who later held the colonists for ransom or exchanged them for their own prisoners of war with the British.

The British government soon decided it had to send additional troops to defend its American colonies against attacks from Indians and intrusions from the French. General Edward Braddock and two regiments arrived in 1755 to expel the French from Fort Duquesne. At the same time, colonial militia units were sent to battle the French and their Indian allies along the New York and New England frontiers. Colonel Washington joined Braddock as his personal aide-de-camp. Within months, however, Braddock’s forces were ambushed, bludgeoned by French and Indian forces, and Braddock was killed. Washington was appointed commander of the Virginia troops, but with limited forces and meager financial support from the Virginia legislature, he had little hope of victory.

Other British forces fared little better during the next three years. Despite having far fewer colonists in North America than the British, the French had established extensive trade networks that helped them sustain a protracted war with support from numerous Indian nations. They also benefited from the help of European and Canadian soldiers as well as Irish conscripts who happily fought their British conquerors. Alternating guerrilla tactics with conventional warfare, the French captured several important forts, built a new one on Lake Champlain, and moved troops deep into British territory. The ineffectiveness of the British and colonial armies also encouraged Indian tribes along the New England and Appalachian frontiers to reclaim land from colonists. Bloody raids devastated many outlying settlements, leading to the death and capture of hundreds of Britain’s colonial subjects.