Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 134

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 115

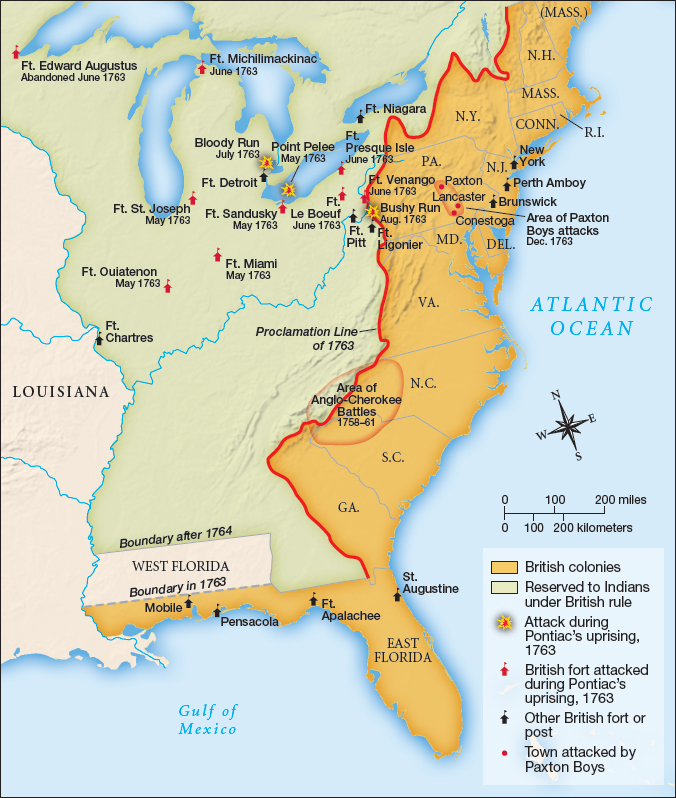

Battles and Boundaries on the Frontier

The sweeping character of the British victory encouraged thousands of colonists to move farther west, into lands once controlled by France. This exacerbated tensions on the southern and western frontiers of British North America, tensions that escalated in the final years of the war and continued long after the Peace of Paris was signed.

In late 1759, for example, the Cherokee nation, reacting to repeated incursions on their hunting grounds, dissolved their long-term trade agreement with South Carolina. Cherokee warriors attacked backcountry farms and homes, leading to counterattacks by British troops. The fighting continued into 1761, when Cherokees on the Virginia frontier launched raids on colonists there. General Jeffrey Amherst then sent 2,800 troops to invade Cherokee territory and end the conflict. The soldiers sacked fifteen villages; killed men, women, and children; and burned acres of fields.

Although British raids diminished the Cherokees’ ability to mount a substantial attack, sporadic assaults on frontier settlements continued for years. These conflicts fueled resentments among backcountry settlers against political leaders in more settled regions of the colonies who rarely provided sufficient funds or soldiers for frontier defense. The raids also intensified hostility toward Indians.

A more serious conflict erupted in the Ohio valley when Indians there realized the consequences of Britain’s victory in Quebec. As the British took over French forts along the Great Lakes and in the Ohio valley in 1760, they immediately antagonized local Indian groups by hunting and fishing on tribal lands and depriving villages of much-needed food. British traders also defrauded Indians on numerous occasions and ignored traditional obligations of gift giving. They refused to provide kettles, gunpowder, or weapons to the Indians and thereby caused near starvation among many tribes that depended on hunting and trade.

The harsh realities of the British regime led some Indians to seek a return to ways of life that preceded the arrival of white men. An Indian visionary named Neolin, known to the British as the Delaware Prophet, preached that Indians had been corrupted by contact with Europeans and urged them to purify themselves by returning to their ancient traditions, abandoning white ways, and reclaiming their lands. Neolin was a prophet, not a warrior, but his message inspired others, including an Ottawa leader named Pontiac.

When news arrived in early 1763 that France was about to cede all of its North American lands to Britain and Spain, Pontiac convened a council of more than four hundred Ottawa, Potawatomi, and Huron leaders near Fort Detroit. Drawing on Neolin’s vision, he mobilized support to drive out the British. In May 1763, Pontiac’s forces laid siege to Detroit and soon gained the support of eighteen Indian nations. They then attacked Fort Pitt and other British frontier outposts and attacked white settlements along the Virginia and Pennsylvania frontier.

Explore

Read part of Pontiac’s speech to a council of Indian tribes in Document 5.1.

Accounts of violent encounters with Indians on the frontier circulated throughout the colonies and sparked resentment among local colonists as well as British troops. Many colonists did not bother to distinguish between friendly and hostile Indians, and General Amherst claimed that all Indians deserved extermination “for the good of mankind.” A group of men from Paxton Creek, Pennsylvania, agreed. In December 1763, they raided families of peaceful, Christian Conestoga Indians near Lancaster, killing thirty. Protests from eastern colonists infuriated the Paxton Boys, who then marched on Philadelphia demanding protection from “savages” on the frontier.

Although violence on the frontier slowly subsided, neither side had achieved victory. Without French support, Pontiac and his followers ran out of guns and ammunition and had to retreat. About the same time, Benjamin Franklin negotiated a truce between the Paxton Boys and the Pennsylvania authorities, but it did not settle the fundamental issues over protection of western settlers. These conflicts convinced the British that the government could not endure further costly frontier clashes. So in October 1763, the crown issued a proclamation forbidding colonial settlement west of a line running down the Appalachian Mountains to create a buffer between Indians and colonists (Map 5.2).

The Proclamation Line of 1763 denied colonists the right to settle west of the Appalachian Mountains. Instituted just months after the Peace of Paris was signed, the Proclamation Line frustrated colonists who sought the economic benefits won by a long and bloody war. Small farmers, backcountry settlers, and squatters had hoped to improve their lot by acquiring rich farmlands, and wealthy land speculators like Washington had staked claims to property no longer threatened by the French or their Indian allies. Now both groups were told to stay put.