Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 209

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 180

Foreign Trade and Foreign Wars

Jefferson and Madison led the faction opposed to Hamilton’s policies. Their supporters were mainly southern Federalists who envisioned the country’s future rooted in agriculture, not the commerce and industry supported by Hamilton and his allies. Jefferson agreed with the Scottish economist Adam Smith that an international division of labor could best provide for the world’s people. Americans could supply Europe with food and raw materials in exchange for clothes and other items manufactured in Europe. When wars in Europe, including a revolution in France, disrupted European agriculture in the 1790s, Jefferson’s views were reinforced.

The French Revolution (1789–1799) had broader implications for U.S. politics than simply increasing the profits from American wheat. The efforts of French revolutionaries to overthrow the monarchy, end feudal practices, and institute a republic gained enthusiastic support from many Americans, especially the followers of Jefferson and Madison. They formed Republican societies, modeled on the Sons of Liberty, to keep tabs on Federalist encroachments on American rights. Many members adopted the French term citizen when addressing each other. Moreover, the strong presence of workers and farmers among France’s revolutionary forces sparked further critiques of the “monied power” that drove Federalist policies.

In late 1792, as French revolutionary leaders began executing thousands of priests, aristocrats, and members of the royal family in the Reign of Terror, wealthy Federalists grew more anxious. The beheading of King Louis XVI horrified them, as did the revolution’s condemnation of Christianity. When France declared war against Prussia, Austria, and finally Great Britain, merchants worried about the impact on trade, and Hamilton feared a loss of valuable revenue from tariffs. In response, Congress passed the Neutrality Act in 1793, prohibiting ships of belligerent nations—including France or Great Britain—from using American ports. This act overrode a 1778 treaty, signed in the midst of the American Revolution, in which the United States had agreed to defend France in any war with Britain.

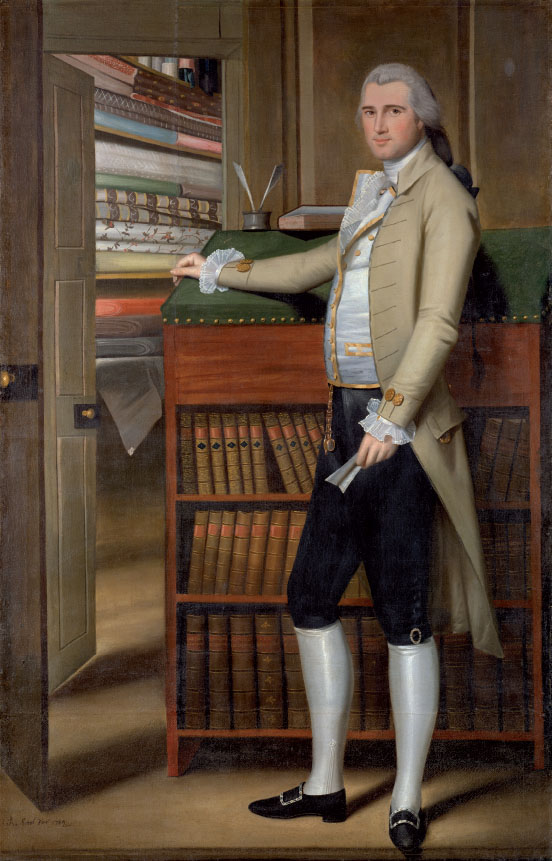

The immediate effect of the Neutrality Act was positive for American merchants. They eagerly increased trade with colonies in the British and French West Indies, and U.S. ships captured much of the lucrative sugar trade. Employment rose, and a building boom transformed seacoast cities as affluent residents hired carpenters, masons, and other craftsmen to construct fashionable homes in the “Federal” style. At the same time, farmers in the Chesapeake and Middle Atlantic regions benefited from European demand for grain, and the price of American wheat soared.

Yet these benefits did not bring about a political reconciliation. Instead, tensions escalated in the spring of 1793 when the French diplomat Edmond Genêt visited the United States. Republican clubs poured out to hear Citizen Genêt speak, and their members donated generously to support the French Revolution. Thousands of young Americans enlisted as volunteers on privateering vessels that harassed British and Spanish shipping in the Caribbean. At the same time, the British navy began stopping U.S. ships carrying French sugar and seized more than 250 vessels. American merchants were outraged and demanded that the government intervene to protect the “free trade” guaranteed by the Neutrality Act.

President Washington sent John Jay to England to negotiate a settlement with the British. In the meantime, Genêt’s popularity began to fade as he sought to pull the United States into the war. Pro-British Federalists were more adamant than Republicans in their disapproval, arguing that Genêt was seeking to provoke conflict. Finally, in August 1793, just as yellow fever erupted in the nation’s capital, Washington demanded Genêt’s recall to France. Jay returned from England in 1794 with a treaty negotiated with the British, although many congressmen thought he had given away too much and were hesitant to ratify it. The treaty, for instance, did not include an agreement by the British to stop impressing American seamen.