Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 214

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 186

The Election of 1800

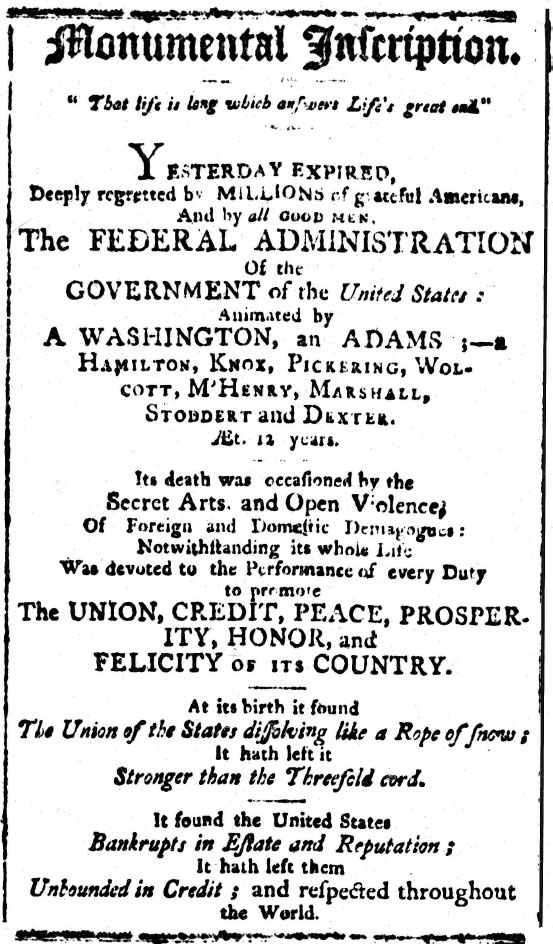

By 1800 Adams had negotiated a peaceful settlement of U.S. conflicts with France, considering it one of the greatest achievements of his administration. However, other Federalists, including Hamilton, disagreed, continuing to seek open warfare and an all-out victory. Thus the Federalists faced the election of 1800 deeply divided. Democratic-Republicans meanwhile, although more loosely organized than the Federalists, united behind Jefferson. They portrayed the Federalists as the “new British,” tyrants who abused their power and violated the rights guaranteed ordinary citizens.

For the first time, congressional caucuses selected candidates for each party. The Federalists agreed on Adams and Charles Cotesworth Pinckney of South Carolina. The Democratic-Republicans again chose Jefferson and Burr as their candidates. The campaign quickly escalated into a series of bitter accusations, with advocates for each side denouncing the other.

In the first highly contested presidential election, the different methods states used to record voters’ preferences gained more attention. Only five states determined members of the electoral college by popular vote. In the rest of the states, legislatures appointed electors. In some states, voters orally declared their preference for president; in other states, voters submitted paper ballots. In addition, because the idea of party tickets was new, the members of the electoral college were not prepared for the situation they faced in January 1801, when Jefferson and Burr received exactly the same number of votes. After considerable political maneuvering, Jefferson, the intended presidential candidate, emerged victorious.

Jefferson labeled his election a revolution achieved not “by the sword” but by “the suffrage of the people.” The election of 1800 was hardly a popular revolution, given the restrictions on suffrage (of some 5.3 million Americans, only about 550,000 could vote) and the limited parti-cipation of voters in selecting the electoral college. Still, partisan factions had been transformed into opposing parties, and the United States had managed a peaceful transition from one party in power to another, which was a development few other nations could claim in 1800.

Review & Relate

|

What were the main issues dividing the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans? |

What do the Alien and Sedition Acts tell us about attitudes toward political partisanship in late-eighteenth-century America? |