Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 236

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 200

Incorporating the Louisiana Territory

Thomas Jefferson had enthusiastically supported the American and French revolutions, but he was not sympathetic to an independent black nation. Nonetheless, in France’s defeat he saw an opportunity to gain navigation rights on the Mississippi River, which the French controlled. This was a matter of crucial concern to Americans living west of the Appalachian Mountains. Jefferson sent fellow Virginian James Monroe to France to offer Napoleon $2 million to ensure Americans the right of navigation and deposit (that is, offloading cargo from ships) on the Mississippi. To Jefferson’s surprise, Napoleon offered instead to sell the entire Louisiana Territory for $15 million.

The president agonized over the constitutionality of such a purchase. Since the Constitution contained no provisions for buying land from foreign nations, a strict interpretation would not allow the purchase. In the end, though, the opportunity proved too tempting, and in late 1803 the president finally agreed to buy the Louisiana Territory based on a loose interpretation of the Constitution. Because the acquisition of the vast territory proved enormously popular among both politicians and ordinary Americans, few cared that it expanded presidential and congressional powers.

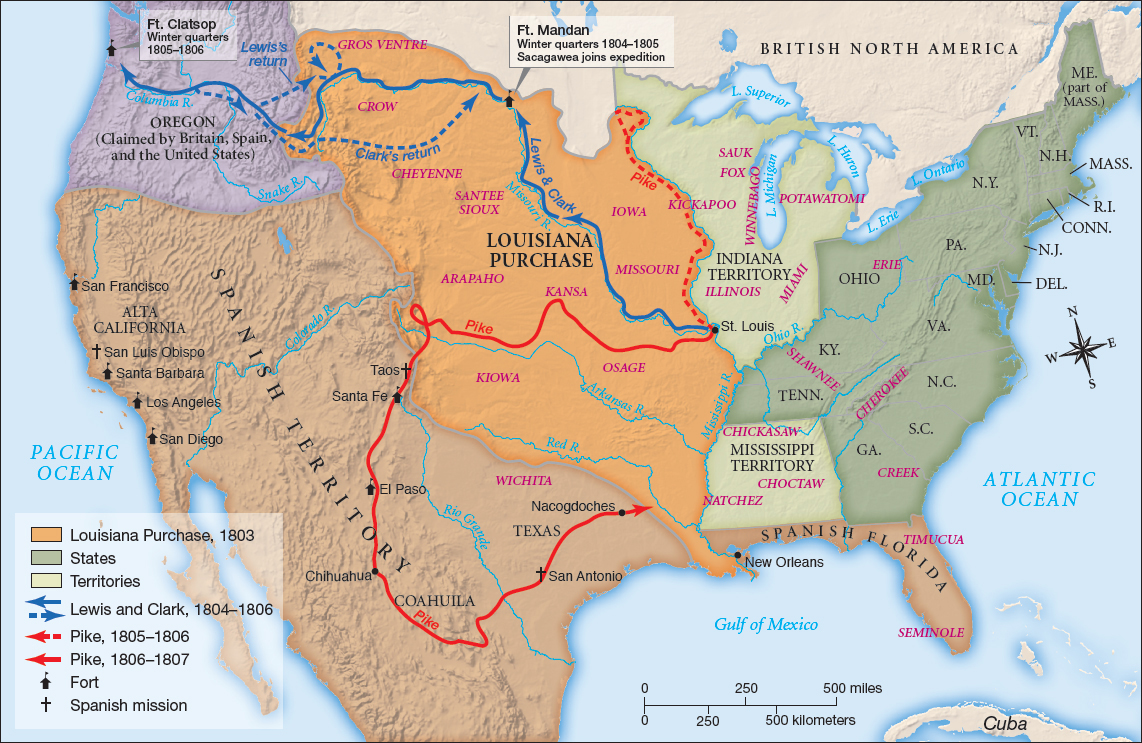

Congress soon appropriated funds for an exploratory expedition known as the Corps of Discovery to map the terrain. This effort, which Sacagawea and her husband joined, was led by Captain Meriwether Lewis, who had served as Jefferson’s personal secretary, and William Clark, an army officer. Beginning on May 14, 1804, Lewis, Clark, and three dozen men traveled thousands of miles up the Missouri River, through the northern plains, over the Rocky Mountains, and beyond the Louisiana Territory to the Pacific coast. Members of the expedition meticulously recorded observations about local plants and animals as well as Indian residents, providing valuable evidence for young scientists like Parker Cleaveland and fascinating information for ordinary Americans.

Sacagawea was the only Indian to travel as a permanent member of the expedition, but other native women and men assisted the Corps when it journeyed near their villages. They provided food and lodging for the travelers, hauled baggage up steep mountain trails, and offered food, horses, and other trade items. The one African American on the expedition, a slave named York, also helped negotiate trade with local Indians. York recognized his value as a trader, hunter, and scout and asked Clark for his freedom when the expedition ended in 1806. York did eventually become a free man, but it is not clear whether it was by Clark’s choice or because York escaped.

Other expeditions followed Lewis and Clark’s successful venture. In 1806 Lieutenant Zebulon Pike led a group to explore the southern portion of the Louisiana Territory (Map 8.1). After traveling from St. Louis to the Rocky Mountains, the expedition traveled into Mexican territory. In early 1807, Pike and his men were captured by Mexican forces. They were returned to the United States at the Louisiana border that July. Pike had learned a great deal about lands that would eventually become part of the United States and about Mexican desires to overthrow Spanish rule, information that proved valuable over the next two decades.

Early in this series of expeditions, in November 1804, Jefferson stood for reelection, winning an easy victory. His popularity among farmers, already high, increased when Congress passed an act that reduced the minimum allotment for federal land sales from 320 to 160 acres. This act allowed more farmers to purchase land on their own rather than via speculators. Yet by the time of his second inauguration in March 1805, the president’s vision of limiting the powers of the federal government had been shattered by his own actions and those of the Supreme Court.