Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 267

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 226

Regional Economic Development

Clay’s American System was intended to bind the various regions of the United States together. Yet even as roads, rivers, canals, and steamboats helped unify a growing nation, they also reinforced the development of regional economies. Although regional ties remained fluid, between 1815 and 1830 increasingly distinct economies developed that promoted the rise of particular labor systems and political priorities.

In the South, for instance, the defeat of the Creek nation, vast Indian land cessions, and the acquisition of Florida ensured the growth of cotton cultivation, which had been initiated by the invention of the cotton gin (see chapter 8). Although the foreign slave trade had ended in 1808, planters extended slavery into new lands to produce cash crops like cotton, sugar, and rice. They used profits from these goods to buy food from the West and shoes and cloth from the North. Small farmers, too, sought to benefit from rising cotton prices, planting as much of their land in cotton as they could. Because continuous cultivation drained nutrients from the soil, planters and small farmers constantly sought more fertile fields, leading to further pressure on those Indians who still controlled large areas of rich southern soil.

When James and Dolley Madison returned to Montpelier in 1817, they experienced the new possibilities and problems of southern agriculture. Plantation homes in long-settled areas like the Virginia piedmont became more fashionable as they incorporated luxury goods imported from China and Europe. The Madisons entertained hundreds of guests, hosted dinners and dances, and provided beds and meals for three dozen people at a time. But soil exhaustion in the region limited the profits from tobacco and made a shift to cotton impossible. While some Virginia planters made money by selling slaves to other planters farther south, James Madison refused to break up slave families who had worked the plantation for decades. With no desire to leave for lands farther west, he and Dolley were forced to reduce their standard of living.

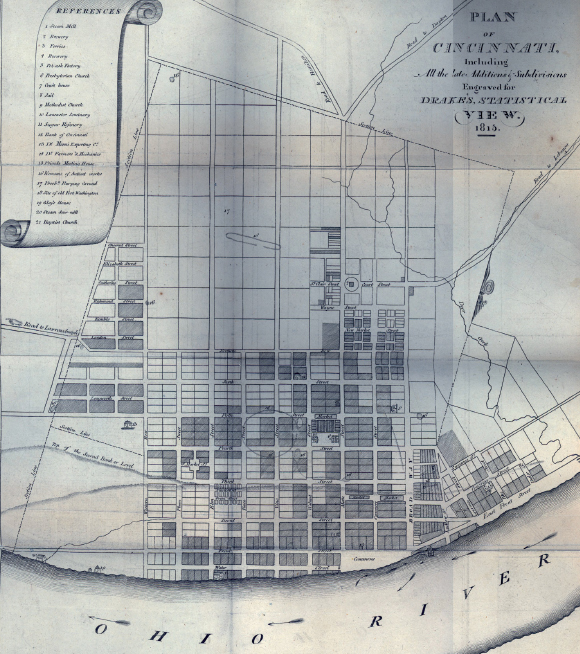

Other white Americans, however, benefited from the expansion of southern agriculture. Of course, many cotton farmers made substantial profits in the 1810s. So did western farmers, who shipped vast quantities of food and other farm products to the South. Towns like Cincinnati, located across the Ohio River from Kentucky, sprang up as regional centers of commerce. In 1811 Cincinnati settlers still confronted Indians along the nearby White Water River. Eight years later, the booming town was incorporated as a city with nearly ten thousand residents.

Americans living in the Northeast increased their commercial connections with the South as well. Northern merchants became more deeply engaged in the southern cotton trade, opening warehouses in port cities like Savannah and Charleston and sending cotton factors, or agents, into the countryside to broker deals with planters. Meanwhile the southern cotton boom fueled industrial expansion. Indeed, factory owners in New England shipped growing amounts of yarn, thread, and cloth along with shoes, tools, and leather goods to the South. As merchants in New England and New York focused on the cotton trade, those in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh built ties to western farmers, exchanging manufactured goods for agricultural products across the Appalachian Mountains.

Review & Relate

|

What role did government play in early-nineteenth-century economic development? |

How and why did economic development contribute to regional differences and shape regional ties? |