Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 275

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 235

The Presidential Election of 1828

The election of 1828 tested the power of the two major factions in the Democratic-Republican Party. President Adams followed the traditional approach of “standing” for office. He told supporters, “If my country wants my services, she must ask for them.” Jackson and his supporters, who deeply distrusted established political leaders, chose instead to “run” for office. They took their case directly to the voters, introducing innovative techniques to create enthusiasm among the electorate.

Van Buren managed the first truly national political campaign in U.S. history, seeking to re-create the original Democratic-Republican coalition among farmers, northern artisans, and southern planters while adding a sizable constituency of frontier voters. He was aided in the effort by Calhoun, who again ran for vice president and supported the Tennessee war hero despite their disagreement over tariffs. Jackson’s supporters organized state party conventions to nominate him for president rather than relying on the congressional caucus. They established local Jackson committees in critical states such as Virginia and New York. They organized newspaper campaigns and developed a logo, the hickory leaf, based on the candidate’s nickname “Old Hickory.”

Jackson traveled the country to build loyalty to himself as well as to his party. His Tennessee background, rise to great wealth, and reputation as an Indian fighter ensured his popularity among southern and western voters. He also reassured southerners that he advocated “judicious” duties on imports, suggesting that he might try to lower the rates imposed in 1828. At the same time, his support of the tariff of 1828 and his military credentials created enthusiasm among northern working men and frontier farmers.

President Adams’s supporters demeaned the “dissolute” and “rowdy” men who poured out for Jackson rallies, and they also launched personal attacks on the candidate. Dragging politicians’ private lives into public view was nothing new, but opposition papers focused their venom this time on the candidate’s wife, Rachel. They questioned the timing of her divorce from her first husband and remarriage to Jackson, suggesting she was an adulterer and a bigamist. Rachel Jackson felt humiliated, but her husband refused to be intimidated by scandal.

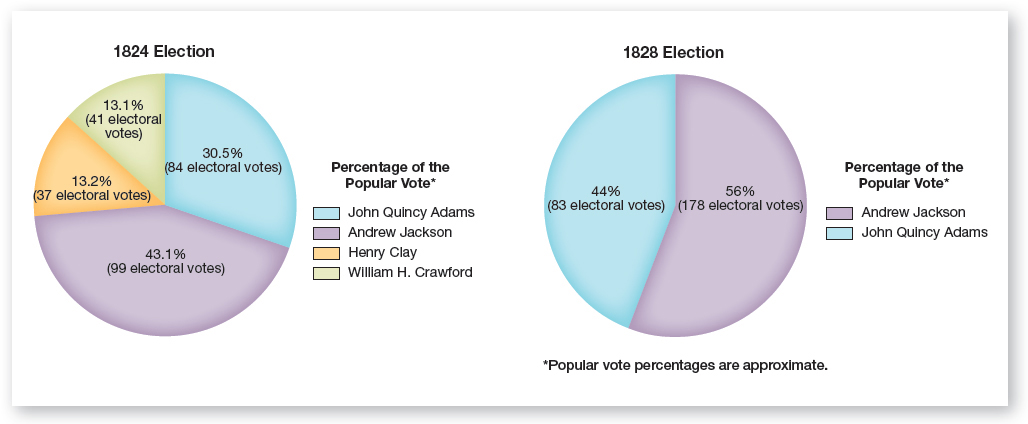

Adams distanced himself from his own campaign. He sought to demonstrate his statesmanlike gentility by letting others speak for him. This strategy worked well when only men of wealth and property could vote. But with an enlarged electorate and an astonishing turnout of more than 50 percent of eligible voters, Adams’s approach failed and Jackson became president. Jackson won handily in the South and the West and carried most of the Middle Atlantic states as well as New York. Adams dominated only in New England (Figure 9.1).

The election of 1828 formalized a new party alignment. During the campaign, Jackson and his supporters referred to themselves as “the Democracy” and forged a new national Democratic Party. In response, Adams’s supporters called themselves National Republicans. The competition between Democrats and National Republicans heightened interest in national politics among ordinary voters and ensured that the innovative techniques introduced by Jackson would be widely adopted in future campaigns. See e-Document Project: The Election of 1828.

Review & Relate

|

How and why did the composition of the electorate change in the 1820s? |

How did Jackson’s 1828 campaign represent a significant departure from earlier patterns in American politics? |