Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 259

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 217

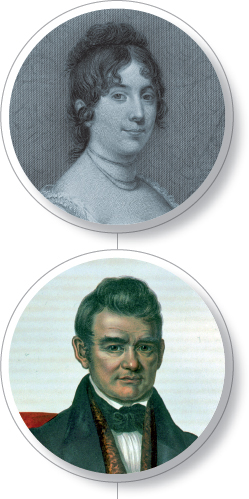

American Histories: Dolley Madison and John Ross

AMERICAN HISTORIES

Dolley Payne, a future First Lady, was raised on a Virginia plantation. But her Quaker parents, moved by the Society of Friends’ growing antislavery sentiment, decided to free their slaves. In 1783, when Dolley was fifteen, the Paynes moved to Philadelphia. There, Dolley’s father suffered heavy economic losses, and Dolley lost her first husband and her younger son to yellow fever. In 1794 the young widow met and married Virginia congressman James Madison. The two made a perfect political couple. James was brilliant but reserved, while Dolley, witty and charming, loved entertaining. When the newly elected president Thomas Jefferson appointed James secretary of state in 1801, the couple moved to Washington.

Since Jefferson and his vice president, Aaron Burr, were widowers, Dolley Madison served as hostess for White House affairs. When James Madison succeeded Jefferson as president in 1809, he, too, depended on his wife’s social skills and networks. Dolley held lively informal receptions to which she invited Federalists, Democratic-Republicans, diplomats, cabinet officers, and their wives. These social events helped bridge the ideological differences that continued to divide Congress and proved crucial in creating a unified front when Congress declared war on Great Britain in 1812.

During the War of 1812, British forces attacked Washington City and burned the Executive Mansion. With the president away, his wife was left to secure important state papers, emerging as a symbol of national courage at a critical moment in the war. When peace came the following year, Dolley Madison quickly reestablished a busy social calendar to help mend conflicts that had erupted during the war.

In 1817, at the end of the president’s second term, the Madisons left Washington for Virginia just as a young Scots-Cherokee trader named John Ross entered the political arena. Born in 1790 in the Cherokee nation, John (also known as Guwisguwi) was the son of a Scottish trader and his wife, who was both Cherokee and Scottish. John Ross was raised in an Anglo-Indian world in eastern Tennessee where he played with Cherokee children and attended tribal ceremonies and festivals but was educated by private tutors and in Protestant missionary schools. At age twenty, Ross was appointed as a U.S. Indian agent among the Cherokees and during the War of 1812 served as an adjutant (or administrative assistant) in a Cherokee regiment.

After the war, Ross focused on business ventures in Tennessee, including the establishment of a plantation. He also became increasingly involved in Cherokee political affairs, using his bilingual skills and Protestant training to represent Indian interests to government officials. In 1819 Ross was elected president of the Cherokee legislature. In the 1820s, he moved to Georgia, near the Cherokee capital of New Echota, where he served as president of the Cherokee constitutional convention in 1827. Having overseen the first written constitution produced by an Indian nation, Ross was then elected principal chief in 1828. Over the next decade, he battled to retain the Cherokee homeland in Georgia, North Carolina, and Tennessee against the pressures of white planters and politicians.•

AMERICAN POLITICS IN the early nineteenth century was a white man’s world, but, as the American histories of Dolley Madison and John Ross demonstrate, it was possible for some of those on the political margins to influence national developments. Both Madison and Ross sought to defend and expand the democratic ideals that defined the young nation. The First Lady helped forge social networks and nurture a nascent political culture in Washington that included women as well as men. At the same time, she struggled with the issue of slavery on her husband’s Montpelier plantation. Ross encouraged the Cherokee people to embrace Anglo-American religion, language, and political ideals in the hopes of providing them with a path to inclusion in the United States. Yet ultimately, given the nation’s economic growth, he could not overcome the power of white planters and politicians to wrest territory from even the most Americanized Indians. Although Ross most directly confronted the limits of American democracy, Dolley Madison also grappled with the dilemmas posed to the nation’s democratic ideals by the expansion of slavery and the limits of citizenship.