Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 279

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 239

Contesting Indian Removal

On another long-standing issue—the acquisition of Indian land—Jackson gained the support of white southerners and most frontier settlers. Yet not all Americans agreed with his effort to remove or exterminate Indians. In the 1820s, nations like the Cherokee that sought to maintain their homelands gained the support of Protestant missionaries who hoped to “civilize” Indians by converting them to Christianity and “American” ways. In 1819 Congress had granted these groups federal funds to establish schools and churches to help acculturate and convert Indian men and women. Presidents James Monroe and John Quincy Adams supported the rights of Indians to maintain their sovereignty if they embraced missionary goals. Jackson was much less supportive of efforts to incorporate Indians into the United States and sided with political leaders who sought to force eastern Indians to accept homelands west of the Mississippi River.

In 1825, three years before Jackson was elected president, Creek Indians in Georgia and Alabama were forcibly removed to Unorganized Territory (previously part of Arkansas Territory and later called Indian Territory) based on a fraudulent treaty. Jackson supported this policy. When he became president, politicians and settlers in Georgia, Florida, the Carolinas, and Illinois demanded federal assistance to force Indian communities out of their states.

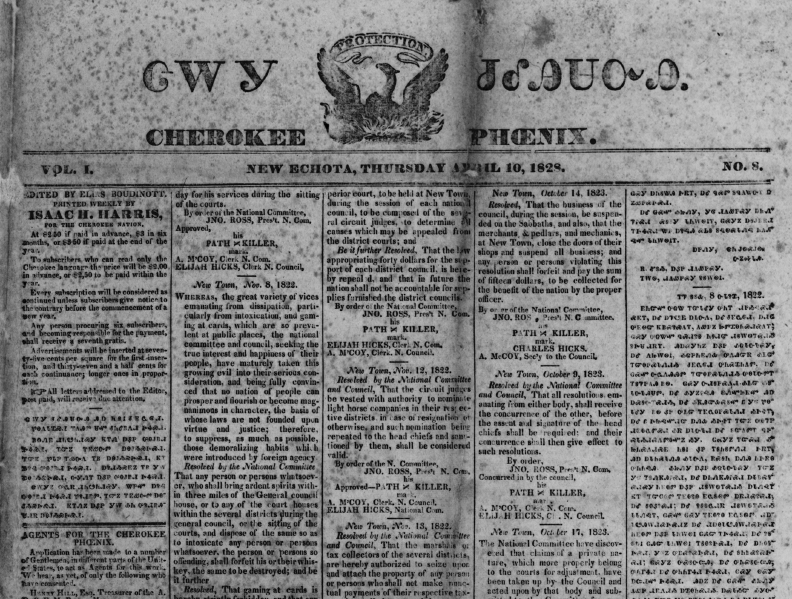

The largest Indian nations vehemently protested their removal. The Cherokees, who had fought against the Creeks alongside Jackson at Horseshoe Bend, adopted a republican form of government in 1827 based on the U.S. Constitution. John Ross served as the president of the Cherokee constitutional convention, and a year later he was chosen principal chief in the first constitutional election. He and the other chiefs then declared themselves a sovereign nation within the borders of the United States. The Georgia legislature rejected the Cherokee claims of independence and argued that Indians were simply guests of the state. When Ross appealed to Jackson to recognize Cherokee sovereignty, the president refused. Instead, Jackson proclaimed that Georgia, like other states, was “sovereign over the people within its borders.” At his urging, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act in 1830, by which the Cherokee and other Indian nations would be forced to exchange ancient claims on lands in the Southeast for a “clear title forever” on territory west of the Mississippi River. Still, the majority of Cherokees refused to accept these terms and worked assiduously to maintain control of their existing territory.

As the dispute between the Cherokee nation and Georgia unfolded, Jackson made clear his intention to implement the Indian Removal Act. In 1832 he sent federal troops into western Illinois to force Sauk and Fox peoples to move farther west. Instead, whole villages, led by Chief Black Hawk, fled to the Wisconsin Territory. Black Hawk and a thousand warriors confronted U.S. troops at Bad Axe, but the Sauk and Fox warriors were decimated in a brutal daylong battle. The survivors were forced to move west. Meanwhile the Seminole Indians, who had fought against Jackson when he invaded Florida in 1818, prepared for another pitched battle to protect their territory, while John Ross pursued legal means to resist removal through state and federal courts. The contest for Indian lands would continue well past Jackson’s presidency, but the president’s desire to force indigenous nations westward would ultimately prevail.

Review & Relate

|

What did President Jackson’s response to the Eaton affair and Indian removal reveal about his vision of democracy? |

To what extent did Jackson’s policies favor the South? Which policies benefited or antagonized which groups of Southerners? |