Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 261

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 220

War Erupts with Britain

Convinced that British officials in Canada fueled Indian resistance, supporters of war with Great Britain demanded an end to British intervention on the western frontier. They were even more concerned about British interference with transatlantic trade. Yet merchants in the Northeast, who depended on trade with Great Britain and the British West Indies, feared the commercial disruptions that war entailed. Once staunch supporters of expanding the power of the national government, New England Federalists now adamantly opposed a declaration of war.

For months, Madison avoided taking a clear stand for or against war. On June 1, 1812, however, having exhausted diplomatic efforts and seeing no end to these conflicts as long as the Napoleonic Wars raged across Europe, Madison sent a secret message to Congress outlining American grievances against Great Britain. Within weeks, Congress declared war by a sharply divided vote of 79 to 49 in the House of Representatives and 19 to 13 in the Senate.

Supporters claimed that a victory over Great Britain would end threats to U.S. sovereignty and raise Americans’ stature in Europe, but the nation was ill prepared to launch a major offensive against such an imposing foe. Cuts in federal spending and falling tax revenues over the previous decade had diminished military resources. Democratic-Republicans had also failed to renew the charter of the Bank of the United States when it expired in 1811, so the nation lacked a vital source of credit. Nonetheless, many in Congress believed that Britain would be too distracted and overcommitted by the ongoing conflict with France to attack North America.

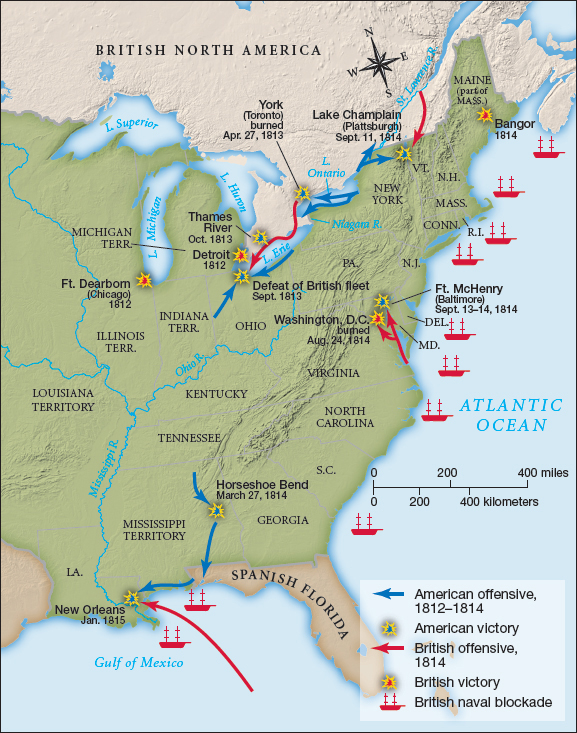

Meanwhile U.S. commanders devised plans to attack Canada. The most enthusiastic advocates of war imagined that the United States could defeat Britain and gain control of all of North America. Initially, however, the U.S. army and navy proved no match for Great Britain and its Indian allies. Tecumseh, who was appointed a brigadier general in the British army, helped capture Detroit. Joint British and Indian forces also launched successful attacks on Fort Dearborn, Fort Mackinac, and other points along the U.S.-Canadian border.

Even as U.S. forces faced defeat after defeat in the summer and fall of 1812, American voters reelected James Madison as president. His narrow victory demonstrated the geographical divisions caused by the war. Madison won most of the western and southern states, where the war was most popular, and was defeated in New England and New York, where Federalist opponents held sway.

After a year of fighting, U.S. forces—with the aid of crucial naval victories on the Great Lakes—finally drove the British back into Canada (Map 9.1). Tecumseh was killed in Canada at the Battle of the Thames, and U.S. forces burned York (present-day Toronto). Yet just as U.S. prospects in the war improved, New England Federalists demanded retreat. In the fall of 1813, state legislatures in New England withdrew their support for any invasions of “foreign British soil,” and Federalists in Congress sought to block appropriations for the war and challenge the deployment of local militia units into the U.S. army.

New England Federalists did not have sufficient power to change national policy, but they called a meeting at Hartford, Connecticut, in 1814 to consider their options. Some participants at the Hartford Convention called for New England’s secession from the United States. Most, however, supported amendments to the U.S. Constitution that would limit presidents to a single term and ensure that presidents were elected from diverse states (so that Virginia planters could not dominate the executive branch). Other amendments would limit embargoes to sixty days and require a two-thirds majority in Congress to declare war, prohibit trade, or admit new states.

The ideas debated at Hartford gained increased attention as British forces once again launched attacks into the United States and British warships blockaded U.S. ports. In August 1814, the British sailed up the Chesapeake. As American troops retreated, Dolley Madison and a family slave, Peter Jennings, gathered up government papers and valuable belongings before fleeing the city. The redcoats then burned and sacked Washington City. The invasion of the U.S. capital was humiliating, but American troops quickly rallied to defeat the British in Maryland and expel them from Washington and New York.

Meanwhile news arrived from the South that in March 1814 militiamen from Tennessee led by Andrew Jackson had defeated a force of Creek Indians, important allies of the British. Cherokee warriors (and adjutant John Ross), longtime foes of the Creeks, joined the fight as well. At the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, in present-day Alabama, the combined U.S.-Cherokee forces slaughtered some eight hundred Creek warriors. Jackson then demanded punitive terms, and in the resulting treaty the Creek nation lost two-thirds of its tribal domain.

Despite sporadic U.S. victories, America was no closer to winning the war. In June 1814, the British finally defeated Napoleon, ending the war in Europe. And in December of that year, the British fleet landed thousands of seasoned troops at New Orleans, threatening U.S. control of that crucial port city. But exhausted from twenty years of European warfare, the British were losing steam as well. As a result, representatives of the two countries met in Ghent, Belgium, to negotiate a peace settlement. On Christmas Eve 1814, the Treaty of Ghent was signed, returning to each nation the lands it controlled before the war.

Although the war had officially ended, it took time for the news to reach the United States. In January 1815, American troops under General Andrew Jackson attacked and routed the British army at New Orleans. The victory cheered Americans, who did not know that peace had already been achieved, and Jackson became a national hero.

Although the War of 1812 achieved no official territorial gains, Jackson’s late victory in the Battle of New Orleans made it appear that American forces had vanquished Great Britain. The war did represent an important defense of U.S. sovereignty and garnered international prestige for the young nation. In addition, Indians on the western frontier lost a powerful ally when British representatives at Ghent failed to act as advocates for their allies. Thus, in practical terms, the U.S. government gained greater control over vast expanses of land in the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys held by these Indian nations.

Review & Relate

|

How were conflicts with Indians in the West connected to ongoing tensions between the United States and Great Britain on land and at sea? |

What were the long-term consequences of the War of 1812? |