Introduction to Chapter 10

10

Slavery Expands South and West

1830–1850

WINDOW TO THE PAST

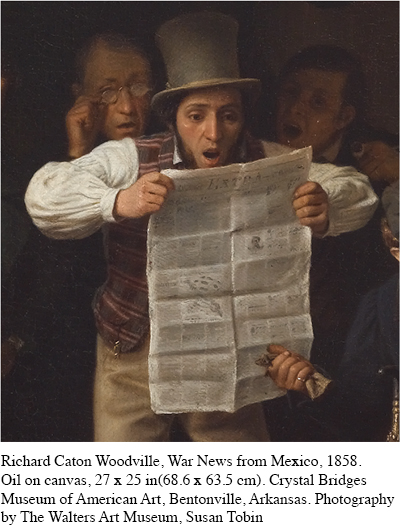

War News from Mexico

The Mexican-American War of 1846–1848 was the first U.S. war that Americans could follow through detailed newspaper coverage. People often shared newspapers with family, friends, and neighbors. Newspapers were also sometimes posted on the buildings where they were printed, and individuals read articles aloud to gatherings of interested men and women. This painting highlights the eagerness with which people awaited the latest reports from Mexico. To discover more about what this primary source can show us, see Document 10.4.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

Explain the development of a plantation society and the impact on planters and their families as well as slaves and their families.

Describe the importance of slave labor and the development of a distinctive slave culture, including forms of slave resistance.

Analyze the differences among southern whites as slavery expanded and compare the techniques used by planters to control blacks and non-slaveholding whites.

Evaluate the challenges that Indians, the panic of 1837, Texas independence, and the Whig Party posed for the Democratic Party.

Discuss the ways that the idea of manifest destiny shaped national elections and intensified debates over slavery.

AMERICAN HISTORIES

Although James Henry Hammond became a wealthy plantation owner, he initially planned to pursue the law. Born in 1807 near Newberry, South Carolina, Hammond opened a law practice in Columbia, the state capital, in 1828. Two years later, bored by his profession, he established a newspaper, the Southern Times. Writing bold editorials that supported nullification of the “Tariff of Abominations,” Hammond quickly gained attention. He soon married Catherine Fitzsimmons, the daughter of a wealthy, politically connected family. The marriage made Hammond the master of Silver Bluff, a 7,500-acre plantation worked by 147 slaves. A successful planter and agricultural reformer, Hammond was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1834.

In 1836 Hammond campaigned successfully for congressional passage of the so-called gag rule, ensuring that antislavery petitions would be tabled rather than read on the floor of the House. Soon afterward, he took ill and resigned from Congress but returned to politics in 1842 as South Carolina’s governor. His ambitions were stymied again, however, when Catherine discovered that her husband had made sexual advances on his four nieces, aged thirteen to sixteen. Fearing public exposure, Hammond withdrew from politics, but then joined southern intellectuals in arguing that slavery was a positive good rather than a necessary evil.

Solomon Northrup was an African American who endured the ravages of slavery and held a distinctly different view of the institution than James Henry Hammond. His father, Mintus, was born into slavery but freed by his owner’s will. He moved to Minerva, New York, married and had a son, Solomon, in 1808. At the age of twenty-one, the free-born Northrup married Anne Hampton and worked transporting goods on the region’s waterways. He was also hired as a fiddle player, while Anne worked as a cook. In 1834 the couple moved to Saratoga Springs, where they raised their three children until tragedy struck.

In March 1841 Northrup met two white circus performers who hired him to play the fiddle for them on tour. They paid his wages up front and told him to obtain documents proving his free status. After reaching Washington, D.C., however, Northrup was drugged, chained, and sold to James Birch, a notorious slave trader. Northrup was resold in New Orleans to William Ford, who changed his name to Platt. Ford put him to work as a raftsman while Northrup tried unsuccessfully to get word to his wife.

In 1842 Ford sold “Platt” to a neighbor, John Tibeats, who, unlike Ford, whipped and abused his workers. When Tibeats attacked Northrup with an ax, he fought back and fled to Ford’s house. His former owner shielded him from Tibeats’s wrath and arranged his sale to the planter Edwin Epps. For the next ten years, Northrup worked the cotton fields and played the fiddle at local dances.

Finally, in 1852 Samuel Bass, a Canadian carpenter who openly acknowledged his antislavery views, came to work on Epps’s house. Northrup persuaded Bass to send a letter to his wife in Saratoga Springs. Anne Northrup, astonished to hear that her husband was still alive, took the letter to lawyer Henry Northrup, the son of Mintus’s former owner. After months of legal efforts, a local judge freed Solomon Northrup in January 1853.

The American histories of James Henry Hammond and Solomon Northrup were both intertwined with the struggle over slavery. By 1850 slave labor had become central to the South’s and the nation’s economic success, even as slave ownership became concentrated in the hands of a small proportion of wealthy white families. These powerful planter families gained increased authority over free blacks and non-slaveowning whites as well as slaves. The concentration of more slaves on each plantation did strengthen African American communities, although it did not negate the brutality they faced. At the same time, the volatility of the cotton market fueled economic instability, contributing to an economic panic in 1837. Planters insisted that only expanding into new lands to cultivate more cotton could ensure economic growth. In response, Democratic administrations forcibly removed Indians from the Southeast, supported independence for Texas, and proclaimed war on Mexico. But these policies led to growing conflicts with western Indian nations, heightened political conflicts over slavery, and inspired the emergence of the Whig Party.

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 311

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 231

Chapter Timeline