Indians Resist Removal

At the same time as the United States and Mexico battled over Texas, the United States also faced continued challenges from Indian nations. After passage of the Indian Removal Act in 1830, Congress hoped to settle the most powerful eastern Indian tribes on land west of the Mississippi River. But some Indian peoples resisted. While federal authorities forcibly removed the majority of Florida Seminoles to Indian Territory between 1832 and 1835, a minority fought back. Jackson and his military commanders expected that this Second Seminole War would be short-lived. However, they misjudged the Seminoles’ strength; the power of their charismatic leader, Osceola; and the resistance of black fugitives living among the Seminoles.

The conflict continued long after Jackson left the presidency. During the seven-year guerrilla war, 1,600 U.S. troops died. U.S. military forces defeated the Seminoles in 1842 only by luring Osceola into an army camp with false promises of a peace settlement. Instead, officers took him captive, finally breaking the back of the resistance. Still, to end the conflict, the U.S. government had to allow fugitive slaves living among the Seminoles to accompany the tribe to Indian Territory.

Unlike the Seminole, members of the Cherokee nation challenged removal by peaceful means, believing that their prolonged efforts to coexist with white society would ensure their success. Indian leaders like John Ross had urged Cherokees to embrace Christianity, white gender roles, and a republican form of government as the best means to ensure control of their communities. Large numbers had done so, but in 1829 and 1830, Georgia officials sought to impose new regulations on the Cherokee living within the state’s borders. Tribal leaders took them to court, demanding recognition as a separate nation and using evidence of their Americanization to claim their rights. In 1831 Cherokee Nation v. Georgia reached the Supreme Court, which denied a central part of the Cherokee claim. It ruled that all Indians were “domestic dependent nations” rather than fully sovereign governments. Yet the following year, in Worcester v. Georgia, the Court declared that the state of Georgia could not impose state laws on the Cherokee, for they had “territorial boundaries, within which their authority is exclusive,” and that both their land and their rights were protected by the federal government.

President Jackson, who sought Cherokee removal, argued that only the tribe’s removal west of the Mississippi River could ensure its “physical comfort,” “political advancement,” and “moral improvement.” Most southern whites, seeking to mine gold and expand cotton production in Cherokee territory, agreed. But Protestant women and men in the North launched a massive petition campaign in 1830 supporting the Cherokees’ right to their land. The Cherokee themselves forestalled action through Jackson’s second term.

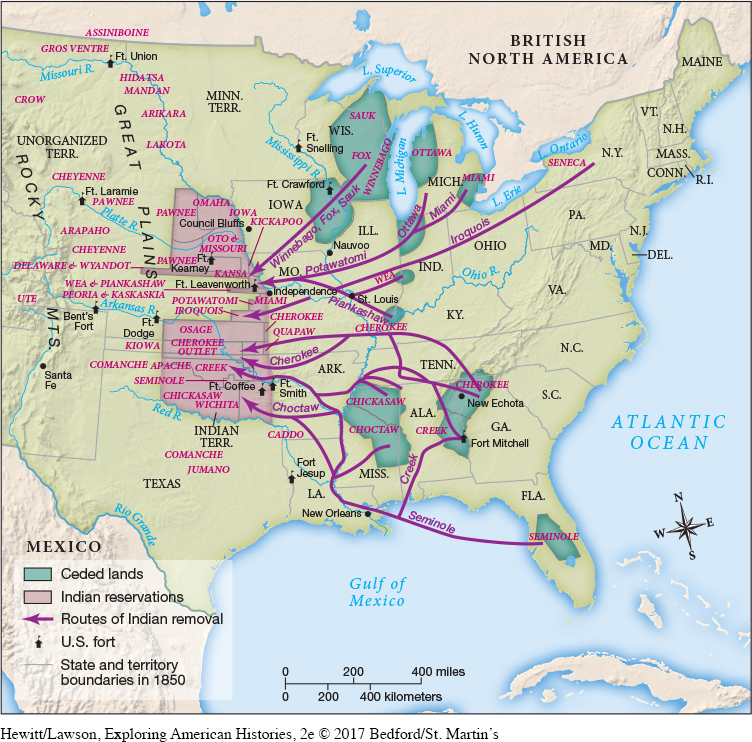

In December 1835, however, U.S. officials convinced a small group of Cherokee men—without tribal sanction—to sign the Treaty of New Echota. It proposed the exchange of 100 million acres of Cherokee land in the Southeast for $68 million and 32 million acres in Indian Territory. Outraged Cherokee leaders like John Ross lobbied Congress to reject the treaty. But in May 1836, Congress approved the treaty by a single vote and set the date for final removal two years later (Map 10.2).

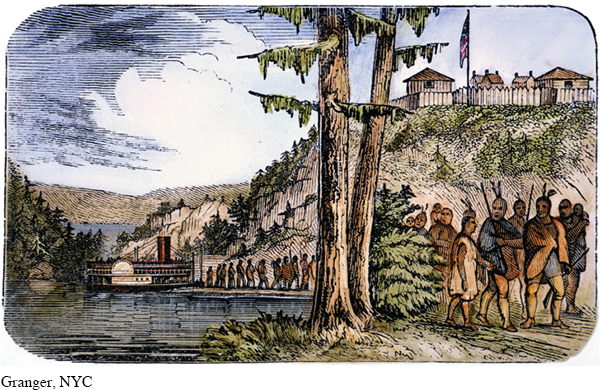

In 1838, the U.S. army forcibly removed Cherokees who had not yet resettled in Indian Territory. That June, General Winfield Scott, assisted by 7,000 U.S. soldiers, forced some 15,000 Cherokees into forts and military camps. Indian families spent the next several months without sufficient food, water, sanitation, or medicine. In October, when the Cherokees finally began the march west, torrential rains were followed by snow. Although the U.S. army planned for a trip of less than three months, the journey actually took five months. As supplies ran short, many Indians died. The remaining Cherokees completed this Trail of Tears, as it became known, in March 1839. But thousands remained near starvation a year later.

Following the Trail of Tears, Seneca Indians petitioned the federal government to stop their removal from western New York. Federal agents had negotiated the Treaty of Buffalo Creek with several Iroquois leaders in 1838. But some Seneca chiefs claimed the negotiation was marred by bribery and fraud. With the aid of Quaker allies, the Seneca petitioned Congress and the president for redress. Perhaps reluctant to repeat the Cherokee and Seminole debacles, Congress approved a new treaty in 1842 that allowed the Seneca to retain two of their four reservations in western New York.

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 328

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 245

Chapter Timeline