The Consequences of Slavery’s Expansion

Outside the South, industry and agriculture increasingly benefited from technological innovation. Planters, however, continued to rely on intensive manual labor. Even reform-minded planters focused on fertilizer and crop rotation rather than machines to enhance productivity. The limited use of new technologies—such as iron plows or seed drills—resulted from a lack of investment capital and planters’ refusal to purchase expensive equipment that they feared might be broken or purposely sabotaged by slaves. Instead, they relied on continually expanding the acreage under cultivation.

One result of these practices was that a declining percentage of white Southerners came to control vast estates with large numbers of enslaved laborers. Between 1830 and 1850, the absolute number of both slaves and owners grew. But slave owners became a smaller proportion of all white Southerners because the white population grew faster than the number of slave owners. At the same time, distinctions among wealthy planters, small slaveholders, and whites who owned no slaves also increased.

The concern with productivity and profits and the concentration of more slaves on large plantations did have some benefits for black women and men. The end of the international slave trade in 1808 forced planters to rely more heavily on natural reproduction to increase their labor force. Thus many planters thought more carefully about how they treated their slaves, who were increasingly viewed as “valuable property.” It was no longer good business to work slaves to death or cripple them by severe punishments.

Nonetheless, owners continued to whip slaves and made paltry investments in their diet and health care. Most slaves lived in small houses with dirt floors and little furniture and clothing. They ate a diet high in calories, especially fats and carbohydrates, but with little meat, fish, fresh vegetables, or fruits. The high mortality rate among slave infants and children—more than twice that of white children to age five—reflected the limits of planters’ care.

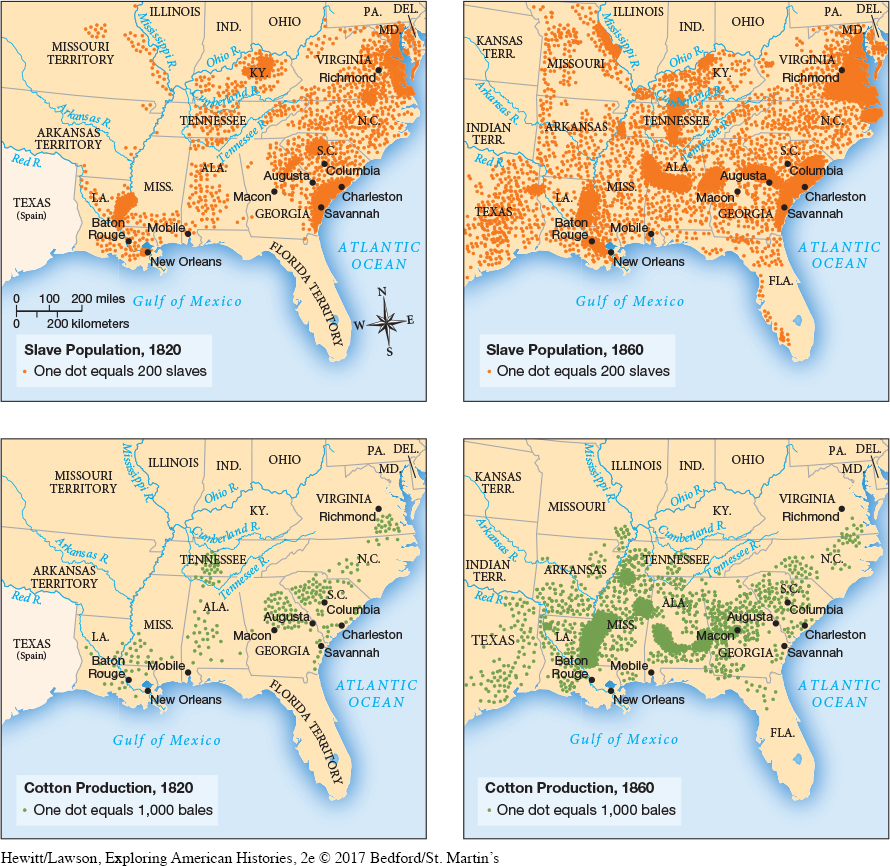

The spread of slavery into Mississippi, Louisiana, Alabama, Missouri, and eventually Texas affected both white and black families, though again not equally. The younger sons of wealthy planters were often forced to move to the frontier, and their families generally lived in rough quarters on isolated plantations. Such moves were far more difficult for slaves, however. Between 1830 and 1850, more than 440,000 slaves were forced to move from the Upper South to the Lower South (Map 10.1), often tearing them away from their families through sales to new masters. On the southern frontier, they endured especially harsh conditions as they cleared and cultivated new lands.

Explore

See Document 10.1 for one visitor’s description of a slave pen in Washington, D.C.

By the 1830s, slave markets blossomed in key cities across the South. Solomon Northrup was held in one in Washington, D.C., where a woman named Eliza watched as her son Randall was “won” by a planter from Baton Rouge. She promised “to be the most faithful slave that ever lived” if he would also buy her and her daughter. The slave trader threatened the desperate mother with a hundred lashes, but neither his threats nor her tears could change the outcome. As slavery spread westward, such scenes were repeated thousands of times.

REVIEW & RELATE

What role did the planter elite play in southern society and politics?

What were the consequences of the dominant position of slave-based plantation agriculture for the southern economy?

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 316

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 235

Chapter Timeline