The Second Great Awakening

Although diverse religious traditions flourished in the United States, evangelical Protestantism proved the most powerful in the 1820s and 1830s. Evangelical churches hosted revivals, celebrated conversions, and organized prayer and missionary societies. This second wave of religious revivals began in Cane Ridge, Kentucky, in 1801, and took root across the South. It then spread northward, transforming Protestant churches and the social fabric of northern life.

Ministers like Charles Grandison Finney adopted techniques first wielded by southern Methodists and Baptists: plain speaking, powerful images, and mass meetings. But Finney molded these techniques for a more affluent audience and held his “camp meetings” in established churches. By the late 1820s, boomtown growth along the Erie Canal aroused deep concerns among religious leaders about the rising tide of sin. In response, the Reverend Finney arrived in Rochester in September 1830. He began preaching in local Presbyterian churches, leading crowded prayer meetings that lasted late into the night. Individual supplicants walked to special benches designated for anxious sinners, who were prayed over in public. Female parishioners played crucial roles, encouraging their husbands, sons, friends, and neighbors to submit to God.

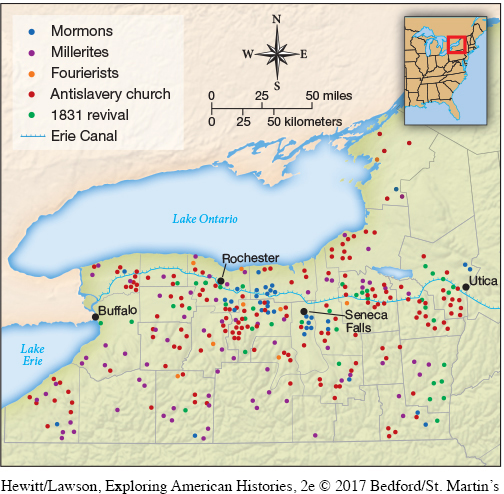

Thousands of Rochester residents joined in the evangelical experience as Finney’s powerful message engulfed other denominations (Map 11.1). The significance of these revivals went far beyond an increase in church membership. Finney converted “the great mass of the most influential people” in the city: merchants, lawyers, doctors, master craftsmen, and shopkeepers. Equally important, he proclaimed that if Christians were “united all over the world the Millennium [Christ’s Second Coming] might be brought about in three months.” Preachers in Rochester and the surrounding towns took up his call, and converts committed themselves to preparing the world for Christ’s arrival.

Developments in Rochester were replicated in cities across the North. Presbyterian, Congregational, and Episcopalian churches overflowed with middle-class and wealthy Americans, while Baptists and Methodists ministered to more laboring women and men. Black Baptists and Methodists evangelized in their own communities, combining powerful preaching with rousing spirituals. In Philadelphia, African Americans built fifteen churches between 1799 and 1830. A few black women joined men in evangelizing to their fellow African Americans.

Tens of thousands of black and white converts embraced evangelicals’ message of moral outreach. No reform movement gained greater impetus from the revivals than temperance, whose advocates sought to moderate and then ban the sale and consumption of alcohol. In the 1820s Americans fifteen years and older consumed six to seven gallons of distilled alcohol per person per year (about double the amount consumed today). Middle-class evangelicals, who once accepted moderate drinking as healthful, now insisted on eliminating alcohol consumption altogether.

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 359

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 267

Chapter Timeline