The New Middle Class

Members of the emerging middle class, which developed mainly in the North, included ambitious businessmen, successful shopkeepers, doctors, and lawyers as well as teachers, journalists, ministers, and other salaried employees. At the top rungs, successful entrepreneurs and professionals adopted affluent lifestyles. At the lower rungs, a growing cohort of salaried clerks and managers hoped that their hard work, honesty, and thrift would be rewarded with upward mobility.

Education, religious affiliation, and sobriety were important indicators of middle-class status. A well-read man who attended a well-established church and drank in strict moderation was marked as belonging to this new rank. He was also expected to own a comfortable home, marry a pious woman, and raise well-behaved children. Entrance to the middle class required the efforts of wives as well as husbands, with many couples adopting new marital ideals of affection and companionship. In most middle-class households, husbands provided financial security while wives managed the domestic realm. Yet this ideal of separate spheres for men and women was flexible, with many wives involved in church work and civic activities and many husbands presiding over the family dinner. Moreover, the ideal had little relevance to the lives of the millions of women toiling on farms, in factories, or as domestic servants.

The rise of the middle class inspired a flood of advice books, ladies’ magazines, religious periodicals, and novels advocating new ideals of womanhood. These publications emphasized the centrality of child rearing and homemaking to women’s identities. This cult of domesticity ideally restricted wives to home and hearth, where they provided their husbands with respite from the cares and corruptions of the world. But women were also expected to cement social and economic bonds by entertaining the wives of business associates, serving in charitable societies, and organizing Sabbath schools. In carrying out these duties, the ideal woman bolstered her family’s status by performing public as well as private roles.

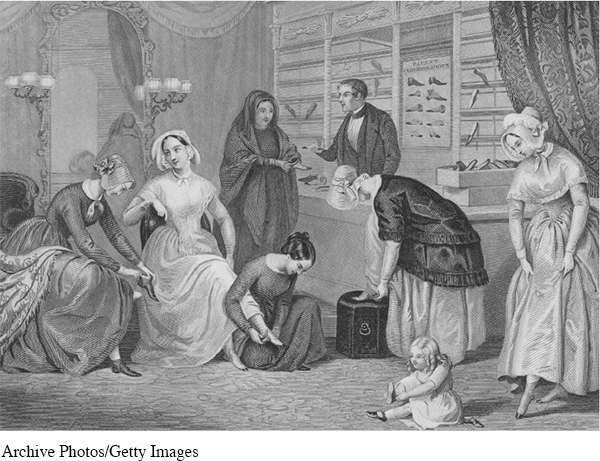

Middle-class families also played a crucial role in the growing market economy. Wives and daughters were responsible for much of the family’s consumption. They purchased cloth, rugs and housewares, and, if wealthy enough, European crystal and Chinese porcelain figures. Middling housewives bought goods once made at home, such as butter and candles, and arranged music lessons and other educational opportunities for their children.

Although increasingly recognized for their ability to consume wisely, middle-class women still performed significant domestic labor. Only upper-middle-class women could afford servants. Most middle-class women cut and sewed garments, cultivated gardens, canned fruits and vegetables, plucked chickens, cooked meals, and washed and ironed clothes. As houses expanded in size and clothes became fancier, these chores remained laborious and time-consuming. But they were also increasingly invisible, focused inwardly on the family rather than outwardly as part of the market economy.

Middle-class men contributed to the consumer economy as well by creating and investing in industrial and commercial ventures. Moreover, in carrying out business and professional obligations, many enjoyed restaurants, the theater, or sporting events. Men attended plays and lectures with their wives and visited museums and circuses with their children. They also purchased hats, suits, mustache wax, and other accouterments of middle-class masculinity.

REVIEW & RELATE

As northern cities became larger and more diverse in the first half of the nineteenth century, what changes and challenges did urban residents face?

What values and beliefs did the emerging American middle class embrace?

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 353

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 261

Chapter Timeline