Introduction to Chapter 12

12

Imperial Ambitions and Sectional Crises

1842–1861

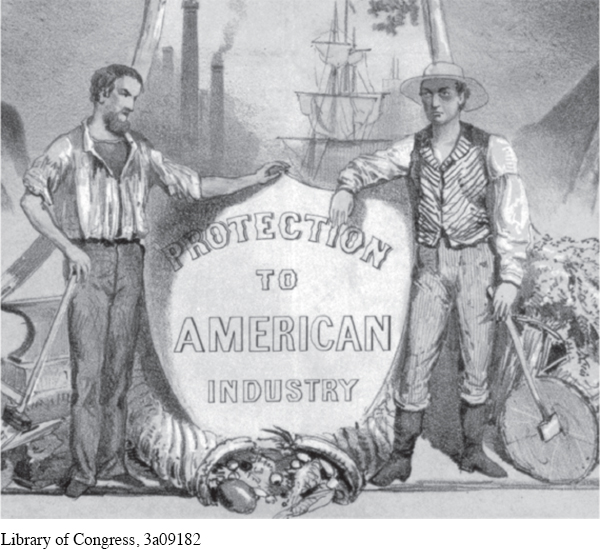

WINDOW TO THE PAST

Republican Party Presidential Ticket, 1860

The Republican Party needed to attract votes from northern farmers, workers, and businessmen to win the 1860 presidential election. It thus produced an image to appeal to voters on the frontier and in cities as well as both workers and elites. The banner shows two men dressed as workers, one holding an ax, with smoke stacks and a ship in the background and a motto promoting higher tariffs. To discover more about what this primary source can show us, see Document 12.4.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

Compare the experiences of different groups living in and migrating to the West.

Explain how geographical expansion heightened sectional conflicts and how those conflicts shaped and were shaped by federal policies like the Compromise of 1850 and the Fugitive Slave Act.

Analyze the ways that the spread of antislavery sentiments, partisan politics, and federal court decisions intensified sectional divisions.

Evaluate the importance of John Brown’s raid and the election of Abraham Lincoln to the presidency in convincing southern states to secede from the Union.

AMERICAN HISTORIES

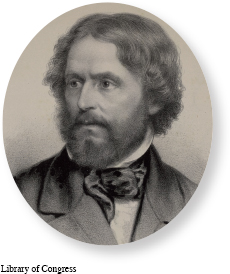

John C. Frémont, a noted explorer and military leader, rose from humble beginnings. He was born out of wedlock to Anne Beverley Whiting Pryor of Savannah, Georgia, who abandoned her wealthy husband and ran off with a French immigrant. Frémont attended the College of Charleston, where he excelled at mathematics, but was eventually expelled for neglecting his studies. At age twenty, in 1833, he was hired to teach aboard a navy ship through the help of an influential South Carolina politician. He then obtained a surveying position to map new railroad lines and Cherokee lands in Georgia and was finally appointed a second lieutenant in the Corps of Topographical Engineers.

In 1840 Lieutenant Frémont moved to Washington, D.C., where he worked on maps and reports based on his surveys. The following year, he eloped with Jessie Benton, the daughter of Missouri senator Thomas Hart Benton. Despite the scandal, Senator Benton supported his son-in-law’s selection for a federally funded expedition to the West. In 1842 Frémont and his guide, Kit Carson, led twenty-three men along the emerging Oregon Trail. Two years later, John returned to Washington, where Jessie helped him turn his notes into a vivid report on the Oregon Territory and California. Congress published the report, which inspired a wave of hopeful migrants to head west.

Frémont’s success was tainted, however, by a quest for personal glory. On a federal mapping expedition in 1845, he left his post and headed to Sacramento, California. In the winter of 1846, he stirred support among U.S. settlers there for war with Mexico. His brash behavior nearly provoked a bloody battle. Frémont then fled to the Oregon Territory, where he and Kit Carson initiated conflicts with local Indians. As the United States moved closer to war with Mexico, Frémont returned to California to support Anglo-American settlers’ efforts to declare the region an independent republic. After the war, Frémont worked tirelessly for California’s admission to the Union and served as one of the state’s first senators. With his wife’s encouragement, he embraced abolition and in 1856 was nominated for president by the new Republican Party.

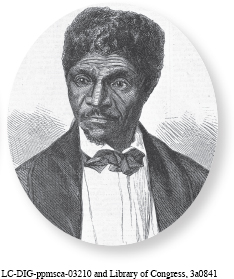

Dred Scott also traveled the frontier in the 1830s and 1840s, but not of his own free will. Born a slave in Southampton, Virginia, around 1800, he and his master, Peter Blow, moved west to Alabama in 1818 and then to St. Louis, Missouri, in 1830. Three years later, Blow sold Scott to Dr. John Emerson, an assistant surgeon in the U.S. army. In 1836 Emerson took Scott to Fort Snelling in the Wisconsin Territory, a free territory. There Scott met Harriet Robinson, a young African American slave. Her master, an Indian agent, allowed the couple to marry in 1837 and transferred ownership of Harriet to Dr. Emerson. When Emerson moved back to St. Louis, the Scotts returned with him. After the doctor’s death in 1843, the couple was hired out to local residents by Emerson’s widow.

In April 1846, the Scotts initiated lawsuits to gain their freedom. The Missouri Supreme Court had ruled in earlier cases that slaves who resided for any time in free territory must be freed, and the Scotts had lived and married in Wisconsin. In 1850 the Missouri Circuit Court ruled in the Scotts’ favor. However, the Emerson family appealed the decision to the state supreme court, with Harriet’s case to follow the outcome of her husband’s. Two years later, that court ruled against all precedent and overturned the lower court’s decision. Dred Scott then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, but it, too, ultimately ruled against the Scotts, leaving them enslaved.

The American histories of John Frémont and Dred Scott were shaped by the explosive combination of westward expansion and growing regional divisions over the issue of slavery. Whereas Frémont joined expeditions to map and conquer the West, Scott followed the migrations of slave owners and soldiers. Both Frémont and Scott were supported by strong women, and both men advocated government action to end slavery. Only Frémont, however, had the right to vote, run for office, and join the Republican Party. From their different positions, these two men reflected the dramatic changes that occurred as westward expansion pushed the issues of empire and slavery to the center of national debate.

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 381

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 282

Chapter Timeline