Popularizing Antislavery Sentiment

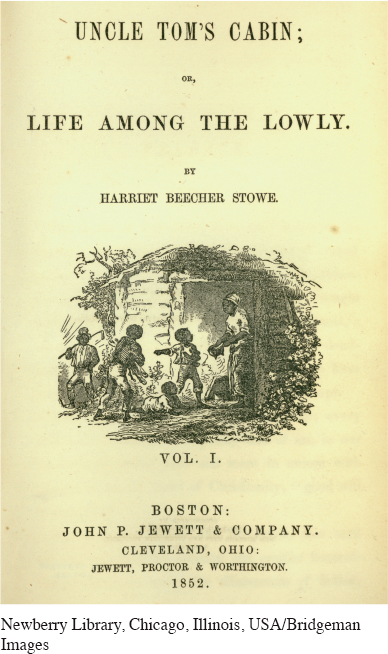

The Fugitive Slave Act forced Northerners to reconsider their role in sustaining the institution of slavery. In 1852, just months before Franklin Pierce was elected president, their concerns were heightened by the publication of the novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe. Stowe’s father, Lyman Beecher, and brother Henry were among the nation’s leading evangelical clergy, and her sister Catharine had opposed Cherokee removal and promoted women’s education. Stowe was inspired to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin by passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850. Published in both serial and book forms, the novel created a national sensation.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin built on accounts by former slaves as well as tales gathered by abolitionist lecturers and writers, which gained growing attention in the North. The autobiographies of Frederick Douglass (1845), Josiah Henson (1849), and Henry Bibb (1849) set the stage for Stowe’s novel. So, too, did the expansion of the antislavery press, which by the 1850s included dozens of newspapers. Antislavery poems and songs also circulated widely and were performed at abolitionist conventions and fund-raising fairs.

Still, nothing captured the public’s attention as did Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Read by millions in the United States and England and translated into French and German, the book reached a mass audience. Its sentimental portrait of saintly slaves and its vivid depiction of cruel masters and overseers offered white Northerners a way to identify with enslaved blacks. Although some African Americans expressed frustration that a white woman’s fictional account gained far more readers than their factual narratives, most recognized the book’s important contribution to the antislavery cause.

Yet the real-life stories of fugitive slaves could often surpass their fictional counterparts for drama. In May 1854 abolitionists sought to free fugitive slave Anthony Burns from a Boston courthouse, where his master was attempting to reclaim him. They failed to secure his release, and Burns was soon marched to the docks to be shipped south. Twenty-two companies of state militia held back tens of thousands of angry Bostonians who lined the streets. A year later, supporters purchased Burns’s freedom from his master, but the incident raised anguished questions among local residents. In a city that was home to so many intellectual, religious, and antislavery leaders, Bostonians wondered how they had come so far in aiding and abetting slavery.

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 397

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 293

Chapter Timeline