Union Politicians Consider Emancipation

By the fall of 1862, African Americans and abolitionists had gained widespread support for emancipation as a necessary goal of the war. Lincoln and his cabinet realized that embracing abolition as a war aim would likely prevent international recognition of southern independence. As Massachusetts senator Charles Sumner proclaimed, “You will observe that I propose no crusade for abolition. [Emancipation] is to be presented strictly as a measure of military necessity.” Still, some Union politicians feared that emancipation might arouse deep animosity in the slaveholding border states and drive them from the Union.

From the Confederate perspective, international recognition was critical. Support from European nations might persuade the North to accept southern independence. More immediately, recognition would ensure markets for southern agriculture and access to manufactured goods and war materiel. Confederate officials were especially focused on Britain, the leading market for cotton and a leading producer of industrial products. President Davis considered sending Rose Greenhow to England to promote the Confederate cause.

Fearing that the British might capitulate to Confederate pressure, abolitionist lecturers toured Britain, reminding residents of their early leadership in the antislavery cause. The Union’s formal commitment to emancipation would certainly increase British support for its position and prevent diplomatic recognition of the Confederacy. By the summer of 1862, Lincoln was convinced, but he wanted to wait for a military victory before making a formal announcement regarding emancipation.

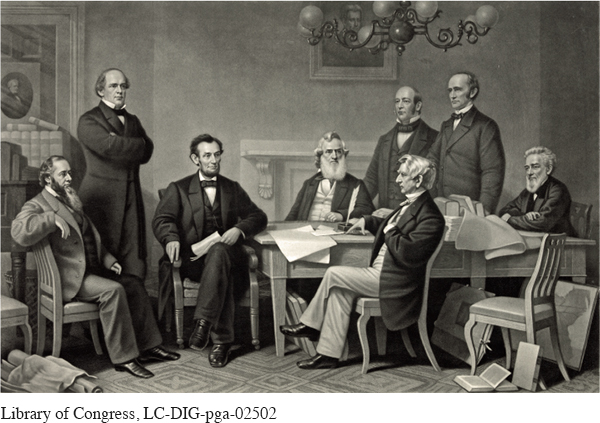

Instead, the Union suffered a series of defeats that summer, and Lee marched his army into Union territory in Maryland. On September 17, Longstreet joined Lee in a fierce battle along Antietam Creek as Union troops brought the Confederate advance to a standstill near the town of Sharpsburg. Union forces suffered more than 12,000 casualties and the Confederates more than 10,000, the bloodiest single day of battle in U.S. history. Yet because Lee and his army were forced to retreat, Lincoln claimed the Battle of Antietam as a great victory. Five days later, the president announced his preliminary Emancipation Proclamation to the assembled cabinet, promising to free slaves in all seceding states.

On January 1, 1863, Lincoln signed the final edict, proclaiming that slaves in areas still in rebellion were “forever free” and inviting them to enlist in the Union army. In many ways, the proclamation was a moderate document. Its provisions exempted from emancipation the 450,000 slaves in the loyal border states, as well as more than 300,000 slaves in Union-occupied areas of Tennessee, Louisiana, and Virginia. The proclamation also justified the abolition of southern slavery on military, not moral, grounds. Despite its limits, the Emancipation Proclamation inspired joyous celebrations among free blacks and white abolitionists, who viewed it as the first step toward slavery’s final eradication. It also ensured the Union army’s full use of black soldiers in the difficult battles ahead.

REVIEW & RELATE

How and why did the Union and the Confederacy treat American Indian and African American participation in the war differently?

What events occurred to make the Civil War become a war to end slavery?

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 424

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 314

Chapter Timeline