Female Progressives and the Poor

Women played the leading role in efforts to improve the lives of the impoverished. Jane Addams had toured Europe after graduating from a women’s college in Illinois. The Toynbee Hall settlement house in London impressed her for its work in helping poor residents of the area. After returning home to Chicago in 1889, Addams and her friend Ellen Starr established Hull House as a center for social reform. Hull House inspired a generation of young women to work directly in immigrant communities. Many were college-educated, professionally trained women who were shut out of jobs in male-dominated professions. Staffed mainly by women, settlement houses became all-purpose urban support centers providing recreational facilities, social activities, and educational classes for neighborhood residents. Calling on women to take up civic housekeeping, Addams maintained that women could protect their individual households from the chaos of industrialization and urbanization only by attacking the sources of that chaos in the community at large.

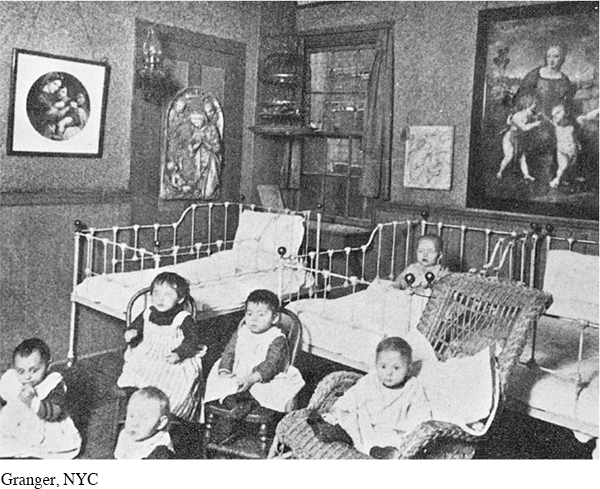

Settlement house and social workers occupied the front lines of humanitarian reform, but they found considerable support from women’s clubs. Formed after the Civil War, these local groups provided middle-class women places to meet, share ideas, and work on common projects. By 1900 these clubs counted 160,000 members. Initially devoted to discussions of religion, culture, and science, club women began to help the needy and lobby for social justice legislation. “Since men are more or less closely absorbed in business,” one club woman remarked about this civic awakening, “it has come to pass that the initiative in civic matters has devolved largely upon women.” Starting out in towns and cities, club women carried their message to state and federal governments and campaigned for legislation that would establish social welfare programs for working women and their children.

In an age of strict racial segregation, African American women formed their own clubs. They sponsored day care centers, kindergartens, and work and home training projects. The activities of black club women, like those of white club women, reflected a class bias, and they tried to lift up poorer blacks to ideals of middle-class womanhood. Yet in doing so, they challenged racist notions that black women and men were incapable of raising healthy and strong families. By 1916 the National Association of Colored Women (NACW), whose motto was “lifting as we climb,” boasted 1,000 clubs and 50,000 members.

White working-class women also organized, but because of employment discrimination there were few, if any, black female industrial workers to join them. Building on the settlement house movement and together with middle-class and wealthy women, working-class women founded the National Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL) in 1903. Recognizing that many women needed to earn an income to help support their families, the WTUL was dedicated to securing higher wages, an eight-hour day, and improved working conditions. Believing women to be physically weaker than men, most female reformers advocated special legislation to protect women in the workplace. They campaigned for state laws prescribing the maximum number of hours women could work, and they succeeded in 1908 when they won a landmark victory in the Supreme Court in Muller v. Oregon, which upheld an Oregon law establishing a ten-hour workday for women. These reformers also convinced lawmakers in forty states to establish pensions for mothers and widows. In 1912 their focus shifted to the federal government with the founding of the Children’s Bureau in the Department of Commerce and Labor. Headed by Julia Lathrop, the bureau collected sociological data and devised a variety of publicly funded social welfare measures. In 1916 Congress enacted a law banning child labor under the age of fourteen (it was declared unconstitutional in 1918). In 1921 Congress passed the Shepherd-Towner Act, which allowed nurses to offer maternal and infant health care information to mothers. See Document Project 19: Muller v. Oregon.

Not all women believed in the idea of protective legislation for women. In 1898 Charlotte Perkins Gilman published Women and Economics, in which she argued against the notion that women were ideally suited for domesticity. She contended that women’s reliance on men was unnatural: “We are the only animal species in which the female depends on the male for food.” Emphasizing the need for economic independence, Gilman advocated the establishment of communal kitchens that would free women from household chores and allow them to compete on equal terms with men in the workplace. Emma Goldman, an anarchist critic of capitalism and middle-class sexual morality, also spoke out against the kind of marriage that made women “keep their mouths shut and their wombs open.” These women considered themselves as feminists—women who aspire to reach their full potential and gain access to the same opportunities as men.

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 621

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 457

Chapter Timeline