Introduction to Chapter 1

1

Mapping Global Frontiers

to 1585

WINDOW TO THE PAST

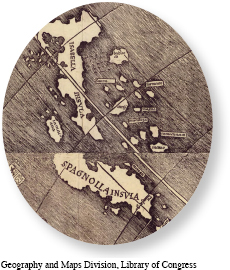

Universalis Cosmographia, 1507

This image of the Americas was engraved on one of the first world maps of the sixteenth century. The elongated shape was based on information supplied by early European explorers. To discover more about what this primary source can show us, see Document 1.1.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

Identify the diverse societies that populated the Americas prior to European exploration.

Explain the reasons for European exploration and expansion, and describe the impact of this expansion on Europe and Africa.

Evaluate the reasons for Europeans’ success in reaching the Americas and the impact of the Columbian Exchange on American Indians, Africans, and Europeans.

Analyze how the Spanish created an empire in the Americas, and describe the impact of Spain’s empire building on Indian empires and European nations.

AMERICAN HISTORIES

In 1519 a young Indian woman named Malintzin was thrust into the center of dramatic events that transformed not only her world but also the world at large. As a young girl, Malintzin, whose birth name is lost to history, lived in the rural area of Coatzacoalcos on the frontier between the expanding kingdom of the Mexica and the declining Mayan states of the Yucatán peninsula. Raised in a noble household, Malintzin was fluent in Nahuatl, the language of the Mexica.

In 1515 or 1516, when she was between the ages of eight and twelve, Malintzin was taken by or given to Mexica merchants, perhaps as a peace offering to stave off military attacks. She then entered a well-established trade in slaves, consisting mostly of women and girls, who were sent eastward to work in the expanding cotton fields or the households of their owners. She may also have been forced into a sexual relationship with a landowner. Whatever her situation, Malintzin learned the Mayan language during her captivity.

In 1517 Mayan villagers sighted Spanish adventurers along local rivers and drove them off. But in 1519 the Spaniards returned. The Maya’s lightweight armor made of dense layers of cotton, cloth, and leather and their wooden arrows were no match for the invaders’ steel swords, guns, and horses. Forced to surrender, the Maya offered the Spaniards food, gold, and twenty enslaved women, including Malintzin. The Spanish leader, Hernán Cortés, baptized the enslaved women and assigned each of them Christian names, although the women did not consent to this ritual. Cortés then divided the women among his senior officers, giving Malintzin to the highest-ranking noble.

Already fluent in Nahuatl and Mayan, Malintzin soon learned Spanish. Within a matter of months, she became the Spaniards’ chief translator. As Cortés moved into territories ruled by the Mexica (whom the Spaniards called Aztecs), his success depended on his ability to understand Aztec ways of thinking and to convince subjugated groups to fight against their despotic rulers. Malintzin thus accompanied Cortés at every step, including his triumphant conquest of the Aztec capital in the fall of 1521.

At the same time that Malintzin played a key role in the conquest of the Aztecs, Martin Waldseemüller sought to map the frontiers along which these conflicts erupted. Born in present-day Germany in the early 1470s, Waldseemüller enrolled at the University of Fribourg in 1490, where he probably studied theology. He would gain fame, however, as a cartographer, or mapmaker.

In 1507 Waldseemüller and Mathias Ringmann, working at a scholarly religious institute in St. Dié in northern France, produced a map of the world, a small globe, and a Latin translation of the four voyages of the Italian explorer Amerigo Vespucci. The map and the globe, entitled Universalis Cosmographia, depict the “known” world as well as the “new” worlds recently discovered by European explorers. The latter include an elongated territory labeled America, in honor of Amerigo, who first recognized that the lands Columbus reached were part of a separate continent. It was set between the continents of Africa and Asia. The map, covering some 36 square feet, offered a view of the world never before attempted.

In 1516 Waldseemüller produced an updated map of the world, the Carta Marina. Apparently in response to challenges regarding Vespucci’s role in discovering new territories, he substituted the term Terra Incognita (“unknown land”) for the region he had earlier labeled America. But the 1507 map had already circulated widely, and America became part of the European lexicon.

The personal histories of Malintzin and Martin Waldseemüller were shaped by the profound consequences of contact between the peoples of Europe and those of the Americas. The Mexica, or Aztec, and the Spanish were affected most significantly in this period, but France and England also sought footholds in the Americas. For centuries, travel and communication between their worlds had been limited. In the sixteenth century, despite significant obstacles, animals, plants, goods, ideas, and people began circulating between Europe and what became known as America. Malintzin and Waldseemüller, in their very different ways, helped map the frontiers of this global society and contributed to the dramatic transformations that followed.

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 1

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 1

Chapter Timeline