Introduction to Chapter 23

23

World War II

1933–1945

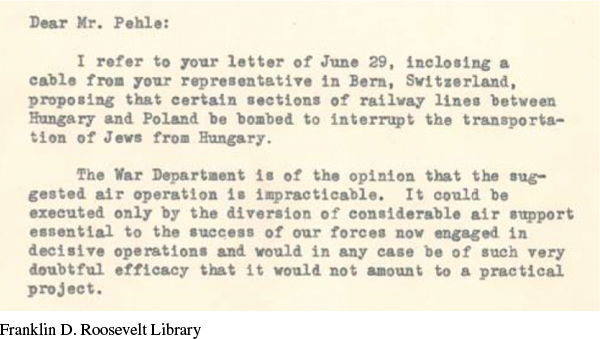

WINDOW TO THE PAST

The War Department on Bombing Railway Lines to Auschwitz, 1944

The Roosevelt administration had to wrestle with the problem of how to respond to the mass slaughter of Jews and other groups in Europe, which it knew was taking place. Although personally sympathetic to the plight of Hitler’s victims, the president did little to intervene. His State Department was riddled with anti-Semitic officials, and the War Department placed military objectives first. To discover more about what this primary source can show us, see Document 23.4.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

Identify the key reasons behind U.S. intervention in World War II and discuss the arguments of those who opposed it.

Describe the effects the war had on the U.S. economy and on the lives of women and families.

Compare and contrast the treatment of minority groups and their responses on the home front.

Discuss the Allied military strategy in fighting World War II on the European and Pacific fronts, including how it affected U.S-Soviet relations and the Holocaust.

AMERICAN HISTORIES

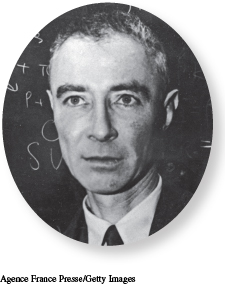

One month after Japan attacked the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt approved a full-scale effort to develop an atomic bomb. As scientific director of this top-secret program, physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer orchestrated the work of more than 3,000 scientists, technicians, and military personnel at the Los Alamos Laboratories near Santa Fe, New Mexico. The son of German American Jews, Oppenheimer helped Jews gain asylum in the United States when the Nazis started persecuting them in the early 1930s.

On July 16, 1945, Oppenheimer and his team successfully tested their new weapon. The explosion lit up the predawn sky with a blast so powerful that it broke a window 125 miles away. A mushroom cloud shot up 41,000 feet into the sky over ground zero, where a 1,200-foot-wide crater had formed. Oppenheimer understood that the world had been permanently transformed. Quoting from Hindu scriptures, he remembered thinking at the moment of the explosion, “I am become death, destroyer of worlds.” Weeks later, in early August 1945, the United States dropped two atomic bombs on Japan, which resulted in over 200,000 deaths.

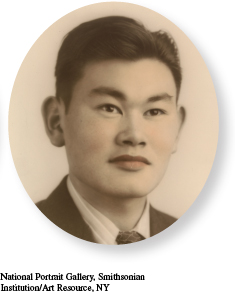

While Oppenheimer and his team remained cloistered at Los Alamos, Fred Korematsu and some 112,000 Japanese Americans lived in internment camps, imprisoned for no other reason than their Japanese ancestry. Born in Oakland, California, in 1919 to Japanese immigrants, Fred grew up like many first-generation Americans. His parents spoke Japanese at home and maintained the cultural traditions of their native land, while their sons learned English in public school, ate hamburgers, and played football and basketball like other children their age. Following graduation from high school, Korematsu worked on the Oakland docks as a welder.

After the 1941 bombing of Pearl Harbor, residents on the West Coast turned their anger on the Japanese and Japanese Americans living among them. As assimilated as Fred Korematsu and many other Nisei (the U.S.-born children of Japanese immigrants) had become, white Americans doubted their loyalty. As a result, Korematsu soon lost his job.

On March 21, 1942, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 authorizing military commanders on the West Coast to take any measures necessary to promote national security. On May 9, the military ordered Korematsu’s family to report to Tanforan Racetrack in San Mateo, from which they would be transported to internment camps throughout the West. Although the rest of his family complied with the order, Fred refused. Three weeks later, he was arrested and then transferred to the Topaz internment camp in south-central Utah. Found guilty of violating the original evacuation order, Korematsu received a sentence of five years of probation. When he appealed his conviction to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1944, the high court upheld the verdict.

The American histories of Fred Korematsu and J. Robert Oppenheimer were shaped by the profound changes brought about by war. Korematsu was subjected to the full force of anti-Japanese sentiment that followed the attack on Pearl Harbor, while Oppenheimer played a key role in developing a weapon that he believed would shorten the war.

The war that these two men experienced in such different ways marked a critical point for the United States in the twentieth century. World War II finally ended the Great Depression, cementing the trend toward government intervention in the economy that had begun with the New Deal. With the war fought almost entirely on foreign soil, the United States converted its factories to wartime production and became the “arsenal of democracy,” putting millions of Americans to work in the process, including African Americans, other minorities, and women. The war also provided opportunities for African Americans to press for civil rights, while at the same time the government trampled on the civil liberties of Japanese Americans. All Americans contributed to the war effort through rationing and higher taxes. Overseas, soldiers fought fierce battles in Europe, Africa, and Asia. The combined military power of the Allies, led by the United States, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union, finally defeated the Axis nations of Germany, Italy, and Japan, but not until the fighting had killed 60 to 70 million people, more than half of whom were civilians, and ushered in the Atomic Age.

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 753

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 554

Chapter Timeline