The Lives of Women

Throughout the 1950s, movies, women’s magazines, mainstream newspapers, and medical and psychological experts informed women that only by embracing domesticity could they achieve personal fulfillment. Dr. Benjamin Spock’s best-selling Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care (1946) advised mothers that their children would reach their full potential only if wives stayed at home and watched over their offspring. In another best seller, Modern Women: The Lost Sex (1947), Ferdinand Lundberg and Marynia Farnham called the independent woman “a contradiction in terms.” A 1951 study of corporate executives found that most businessmen viewed the ideal wife as one who devoted herself to her husband’s career. College newspapers described female undergraduates who were not engaged by their senior year as distraught. Certainly many women professed to find domestic lives fulfilling, but not all women were so content. Many experienced anxiety and depression. Far from satisfied, these women suffered from what the social critic Betty Friedan would later call “a problem that has no name,” a malady that derived not from any personal failing but from the unrewarding roles women were expected to play.

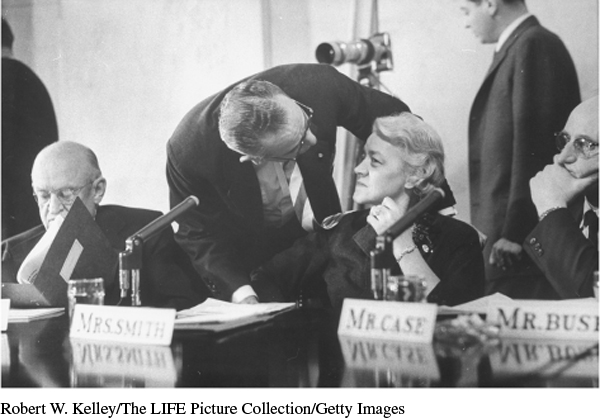

Not all women fit the stereotype. Although most married women with families did not work during the 1950s, the proportion of working wives doubled from 15 percent in 1940 to 30 percent in 1960, with the greatest increase coming among women over the age of thirty-five. Married women were more likely to work if they were African American or came from working-class immigrant families. Moreover, women’s magazines offered readers a more complex message than domesticity. Alongside articles about and advertisements directed at stay-at-home mothers, these periodicals profiled career women, such as Maine senator Margaret Chase Smith, the African American educator Mary McLeod Bethune, and sports figures such as the golf and tennis great Babe (Mildred) Didrikson Zaharias. At the same time, working women played significant roles in labor unions, where they fought to reduce disparities between men’s and women’s income and provide a wage for housewives, recognizing the importance of their unpaid work to maintaining families. Many other women joined clubs and organizations like the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA), where they engaged in charitable and public service activities. Some participated in political organizations, such as Henry Wallace’s Progressive Party, and peace groups, such as the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, to campaign against the violence caused by racial discrimination at home and Cold War rivalries abroad.

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 836

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 616

Chapter Timeline