The Montgomery Bus Boycott

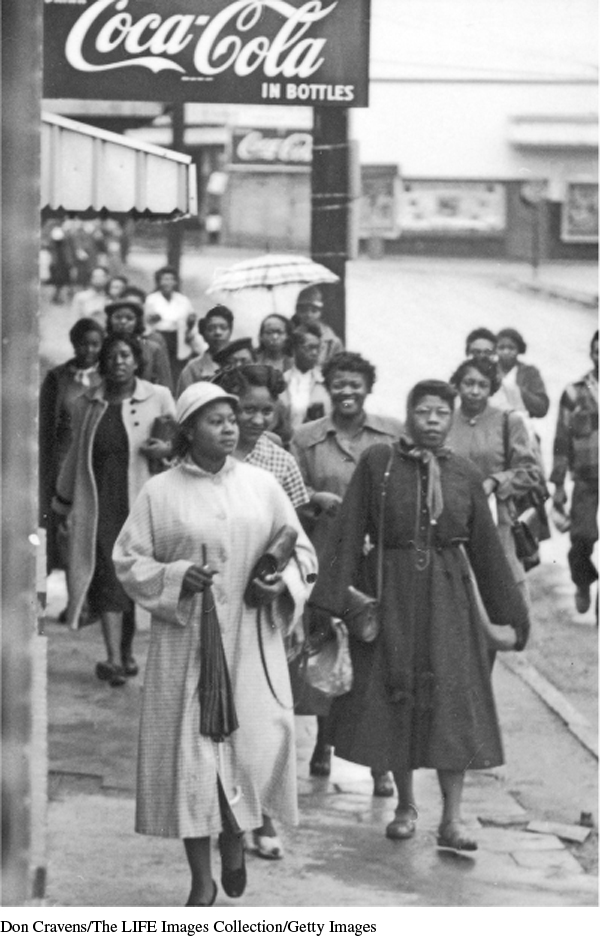

The Brown decision encouraged African Americans to protest against other forms of racial discrimination. In 1955 in Montgomery, Alabama, the Women’s Political Council, a group of middle-class and professional black women, petitioned the city commission to improve bus service for black passengers. Among other things, they wanted blacks not to have to give up their seats to white passengers who boarded the bus after black passengers did. Their requests went unheeded until December 1, 1955, when Rosa Parks, a black seamstress and an NAACP activist, refused to give up her seat to a white man. Parks’s arrest rallied civic, labor, and religious groups and sparked a bus boycott that involved nearly the entire black community. Instead of riding buses, black commuters walked to work or joined car pools. White officials refused to capitulate and fought back by arresting leaders of the Montgomery Improvement Association, the organization that coordinated the protest. Other whites hurled insults at blacks and engaged in violence. After more than a year of conflict, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the complete desegregation of Montgomery’s buses.

Out of this landmark struggle, Martin Luther King Jr. emerged as the civil rights movement’s most charismatic leader. His personal courage and power of oratory could inspire nearly all segments of the African American community. Twenty-six years old at the time of Parks’s arrest, King was the pastor of the prestigious Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. Though King was familiar with the nonviolent methods of the Indian revolutionary Mohandas Gandhi and the civil disobedience of the nineteenth-century writer Henry David Thoreau, he drew his inspiration and commitment to these principles mainly from the black church and secular leaders such as A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin. King understood how to convey the goals of the civil rights movement to sympathetic white Americans, but his vision and passion grew out of black communities. At the outset of the Montgomery bus boycott, King noted proudly of the boycott: “When the history books are written in future generations, the historians will have to pause and say ‘There lived a great people—a Black people—who injected new meaning and dignity into the veins of civilization.’ ”

The Montgomery bus boycott made King a national civil rights leader, but it did not guarantee him further success. In 1957 King and a like-minded group of southern black ministers formed the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to spread nonviolent protest throughout the region, but except in a few cities, such as Tallahassee, Florida, additional bus boycotts did not take hold.

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 841

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 621

Chapter Timeline