Introduction to Chapter 26

26

Liberalism and Its Challengers

1960–1973

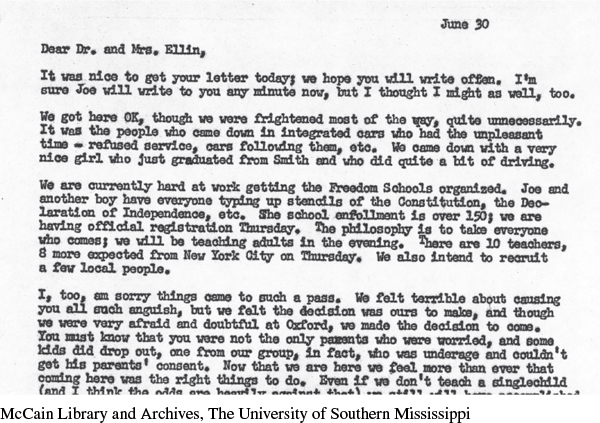

WINDOW TO THE PAST

Nancy Ellin, Letter Describing Freedom Summer, 1964

In 1964, white and black volunteers spent a summer in Mississippi attempting to register voters and establishing Freedom Schools. Often surrounded by danger, they wrote letters to family and friends, such as the letter here, explaining the work they did, problems they encountered, and the courage of local blacks. To discover more about what this primary source can show us, see Document 26.6.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

Discuss President Kennedy’s approaches to liberalism at home and in foreign affairs.

Explain how the civil rights movement succeeded in convincing the federal government to enact the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Identify the major legislative accomplishments of the Great Society.

Explain why U.S. intervention in Vietnam escalated in the 1960s.

Examine the challenges to liberalism from the political left and right and analyze their similarities and differences.

AMERICAN HISTORIES

As attorney general of California at the outset of World War II, Earl Warren helped convince President Franklin D. Roosevelt to order the relocation of 110,000 Japanese Americans. After the war, as governor, he continued to fight against perceived threats to national security by joining the anti-Communist crusade. In 1953 President Dwight D. Eisenhower appointed Warren to be chief justice of the United States, a choice that many observers saw as a safe conservative pick.

As chief justice, however, Warren defied expectations and instead led the Supreme Court in a liberal direction. In 1954 Warren wrote the landmark opinion ordering school desegregation in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas. The Warren Court did not shrink from controversy, and its rulings expanding the rights of accused criminals, banning prayer in public school classrooms, and upholding birth control as a right of privacy evoked harsh criticism from the police, religious fundamentalists, and conservative politicians.

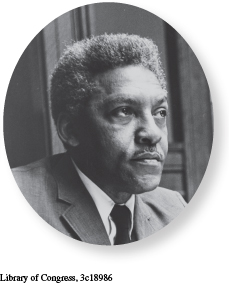

Unlike Earl Warren, Bayard Rustin worked outside of regular political and social channels to achieve change. Rustin joined the Young Communist League in the 1930s because of its commitment to economic justice, racial equality, and international peace. As a committed pacifist, however, Rustin quit the organization in 1941 when the party supported U.S. intervention in World War II and retreated on its fight against racial discrimination during the war.

In 1942 Rustin helped found the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), an interracial organization that pioneered nonviolent, direct-action protests against racial bias. Rustin was imprisoned from 1943 to 1946 for declining to perform alternative service after he refused to register for the military draft. Following his release, in 1947 Rustin helped plan and lead the Journey of Reconciliation, which challenged segregation on interstate buses in the South. In the 1950s and 1960s, he became an adviser to Martin Luther King Jr. and a major strategist in the civil rights movement in his own right.

Rustin remained active in various causes throughout his life. One of his last efforts was perhaps his most personal: the struggle against antigay prejudice. As a homosexual, Rustin had to conceal his sexual identity at a time when the public and his political allies rejected homosexuals. In the 1980s, as the gay liberation movement grew more vocal, Rustin spoke out for tolerance and equality until his death in 1987.

The American histories of Earl Warren and Bayard Rustin demonstrate the complexity of social change. The federal government had the power to encourage social movements by interpreting the Constitution, enacting legislation, and enforcing the law in a manner that eliminated barriers to racial, sexual, and political equality. Yet federal action likely would not have happened without the pressure applied by activists like Rustin. As president, Lyndon Johnson took action with his Great Society programs, but his escalation of the war in Vietnam divided his party and generated opposition from young activists on the left. At the same time, efforts to promote equality and social justice, along with the military stalemate in Vietnam, produced a strong reaction from conservatives who sought to roll back liberal gains; pursue their own policies of small government, low taxes, and self-help; and bring about a quick but honorable end to the war.

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 857

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 623

Chapter Timeline