Liberation Movements

The varieties of political protest and cultural dissent emboldened other oppressed groups to emancipate themselves. Women, Latinos, Indians, and gay Americans all launched liberation movements.

Despite passage of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920, which gave women the right to vote, women did not have equal access to employment, wages, or education or control over reproduction. Nor did they have sufficient political power to remove these obstacles to full equality. Yet by 1960 nearly 40 percent of all women held jobs, and women made up 35 percent of college enrollments. The social movements of the 1960s—civil rights, the New Left, and the counterculture—attracted large numbers of women. Groups like SNCC empowered female staff in community-organizing projects, and women also played central roles in antiwar efforts, leading many to demand their own movement for liberation.

The women’s liberation movement also built on efforts of the federal government to address gender discrimination. In 1961 President Kennedy appointed the Commission on the Status of Women. The commission’s report, American Women, issued in 1963, reaffirmed the primary role of women in raising the family but cataloged the inequities women faced in the workplace. In 1963 Congress passed the Equal Pay Act, which required employers to give men and women equal pay for equal work. The following year, the 1964 Civil Rights Act opened up further opportunities when it prohibited sexual bias in employment and created the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC).

In 1963 Betty Friedan published a landmark book, The Feminine Mystique, which questioned society’s prescribed gender roles and raised the consciousness of mostly college-educated women. In The Feminine Mystique, she described the post-college isolation and alienation experienced by her female friends who got married and stayed home to care for their children. However, not all women saw themselves reflected in Friedan’s book. Many working-class women and those from African American and other minority families had not had the opportunity to attend college or stay home with their children, and younger college women had not yet experienced the burdens of domestic isolation.

Nevertheless, in October 1966, Betty Friedan and like-minded women formed the National Organization for Women (NOW). With Friedan as president, NOW dedicated itself to moving society toward “true equality for all women in America, and toward a fully equal partnership of the sexes.” NOW called on the EEOC to enforce women’s employment rights more vigorously and favored passage of an Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), paid maternity leave for working women, the establishment of child care centers, and reproductive rights. Although NOW advocated job training programs and assistance for impoverished women, it attracted a mainly middle-class white membership. Some blacks were among its charter members, but most African American women chose to concentrate first on eliminating racial barriers that affected black women and men alike. Some union women also continued to oppose the ERA, and antiabortion advocates wanted to steer clear of NOW’s support for reproductive rights.

Young women, black and white, had also faced discrimination, sometimes in unexpected places. Even within the civil rights movement women were not always treated equally, often being assigned clerical duties. Men held a higher status within the antiwar movement because women were not eligible for the draft. Ironically, men’s claims of moral advantage justified many of them in seeking sexual favors. “Girls say yes to guys who say no,” quipped draft-resisting men who sought to put women in their traditional place.

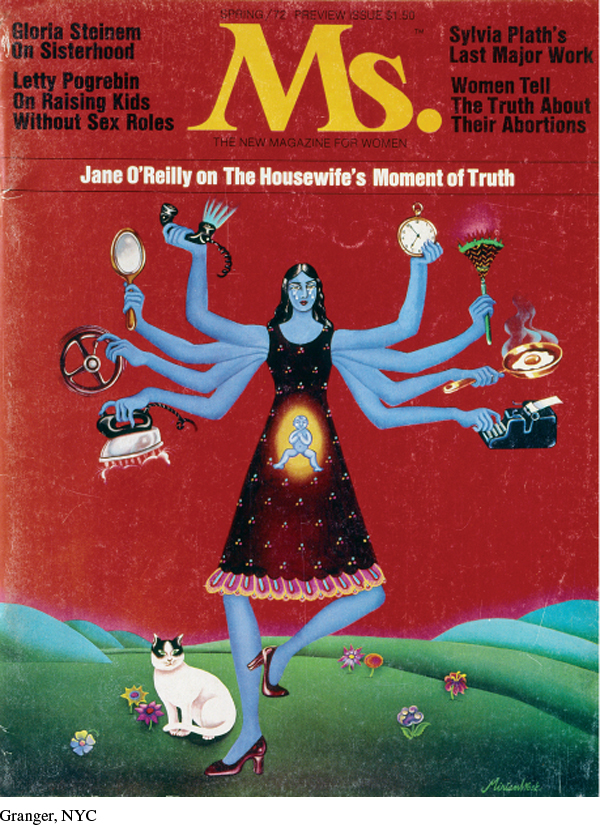

As a result of these experiences, radical women formed their own, mainly local organizations. They created “consciousness-raising” groups that allowed them to share their experiences of oppression in the family, the workplace, the university, and movement organizations. These women’s liberationists went beyond NOW’s emphasis on legal equality and attacked male domination, or patriarchy, as a crucial source of women’s subordination. They criticized the nuclear family and cultural values that glorified women as the object of male sexual desires, and they protested creatively against discrimination. In 1968 radical feminists picketed the popular Miss America contest in Atlantic City, New Jersey, and set up a “Freedom Trash Can” into which they threw undergarments and cosmetics. Radical groups such as the Redstockings condemned all men as oppressors and formed separate female collectives to affirm their identities as women.

In 1973 feminists won a major battle in the Supreme Court over a woman’s right to control reproduction. In Roe v. Wade, the high court ruled that states could not prevent a woman from obtaining an abortion in the first three months of pregnancy but could impose some limits in the next two trimesters. In furthering the constitutional right of privacy for women, the justices classified abortion as a private medical issue between a patient and her doctor. This decision marked a victory for a woman’s right to choose to terminate her pregnancy, but it also stirred up a fierce reaction from women and men who considered abortion to be the murder of an unborn child.

Latinas joined the feminist movement, often forming their own organizations, but they, like black women, also joined men in struggles for racial equality and advancement. During the 1960s, the size of the Spanish-speaking population in the United States tripled from three million to nine million. Hispanic Americans were a diverse group who hailed from many countries and backgrounds. In the 1950s, Cesar Chavez had emerged as the leader of oppressed Mexican farmworkers in California. In seeking the right to organize a union and gain higher wages and better working conditions, Chavez shared King’s nonviolent principles. In 1962 Chavez formed the National Farm Workers Association, and in 1965 the union called a strike against California grape growers, one that attracted national support and finally succeeded after five years.

Younger Mexican Americans, especially those in cities such as Los Angeles and other western barrios (ghettos), supported Chavez’s economic goals but challenged older political leaders who sought cultural assimilation. Borrowing from the Black Panthers, Mexican Americans formed the Brown Berets, a self-defense organization. In 1969 some 1,500 activists gathered in Denver and declared themselves Chicanos, a term that expressed their cultural pride and identity. Chicanos created a new political party, La Raza Unida (The United Race), to promote their interests, and the party and its allies sponsored demonstrations to fight for jobs, bilingual education, and the creation of Chicano studies programs in colleges. Chicano and other Spanish-language communities also took advantage of the protections of the Voting Rights Act, which in 1975 was amended to include sections of the country—from New York to California to Florida and Texas—where Hispanic literacy in English and voter registration were low.

In similar fashion, Puerto Ricans organized the Young Lords Party (YLP). Originating in Chicago in 1969, the group soon spread to New York City. Like the Black Panthers, the organization established inner-city breakfast programs and medical clinics. The YLP supported bilingual education in public schools, condemned U.S. imperialism, favored independence for Puerto Rico, and supported women’s reproductive rights.

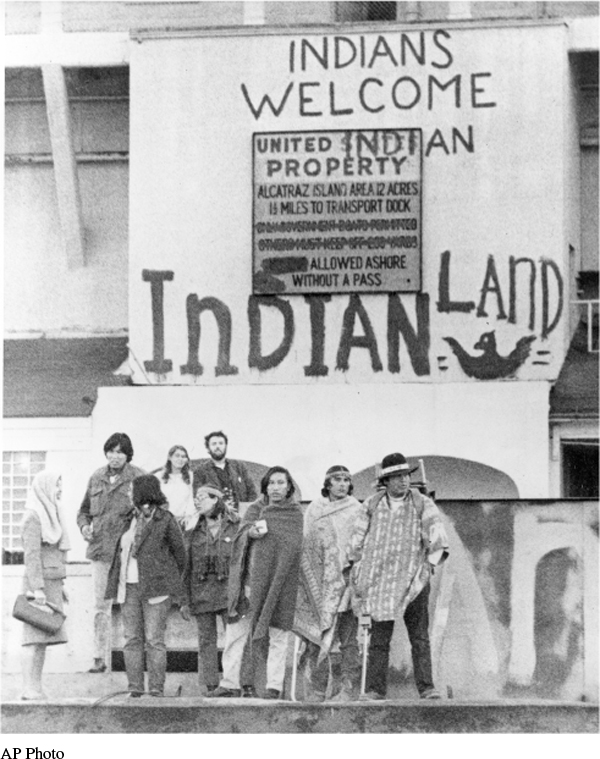

American Indians also joined the upsurge of activism and self-determination. By 1970 some 800,000 people identified themselves as American Indians, many of whom lived in poverty on reservations. They suffered from inadequate housing, high alcoholism rates, low life expectancy, staggering unemployment, and lack of education. Conscious of their heritage as the first Americans, they determined to halt their deterioration by asserting “red” pride and established the American Indian Movement (AIM) in 1968. The following year, Indians occupied the abandoned prison island of Alcatraz in San Francisco Bay, where they remained until 1971. In 1972 AIM occupied the headquarters of the Federal Bureau of Indian Affairs in Washington, D.C. AIM demonstrators also seized the village of Wounded Knee, South Dakota, the scene of the 1890 massacre of Sioux residents by the U.S. army, to dramatize the impoverished living conditions on reservations. They held on for more than seventy days with eleven hostages until a shootout with the FBI ended the confrontation, killing one protester and wounding another.

Explore

See Documents 26.2 and 26.3 for statements on Chicano and American Indian protests.

The results of the red power movement proved mixed. Demonstrations focused media attention on the plight of American Indians but did little to halt their downward spiral. Nevertheless, courts became more sensitive to Indian claims and protected mineral and fishing rights on reservations.

Asian American college students on the West Coast formed their own liberation struggle. At the University of California, Berkeley, and San Francisco State University, they participated in demonstrations against the Vietnam War and racism. In 1968 Asian American students at San Francisco State joined the Third World Liberation Front and, along with the Black Student Union, went on strike for five months, succeeding in the establishment of programs in Asian American and Black studies.

The children of newly arrived Chinese immigrants faced different problems, doing poorly in public schools that taught exclusively in English. Established in 1969, the Chinese for Affirmative Action filed a lawsuit against San Francisco school officials for discriminating against students with limited English-language skills. In Lau v. Nichols (1974), the Supreme Court upheld the group’s claim, accelerating opportunities for bilingual education.

During this period many Japanese American high school and college students learned for the first time about their parents and grandparents’ internment during World War II. Like other activists, they expressed pride in their ethnic heritage and joined in efforts to publicize the injustices that earlier generations had endured. The activism of this third generation of Japanese helped convince the moderate Japanese American Citizens League in 1970 to endorse reparations for the internees, the first step in an ultimately successful two-decade effort.

Unlike African Americans, Chicanos, American Indians, and Asian Americans, homosexuals were not distinguished by the color of their skin. Estimated at 10 percent of the population, gays and lesbians remained largely invisible to the rest of society. In the 1950s, gay men and women created their own political and cultural organizations and frequented bars and taverns outside mainstream commercial culture, but most lesbians and gay men, like Bayard Rustin, hid their identities. It was not until 1969 that they took a major step toward asserting their collective grievances in a very visible fashion. Police regularly cracked down on gay bars like the Stonewall Tavern in New York City’s Greenwich Village. But on June 27, 1969, gay patrons battled back. The Village Voice called the Stonewall riots “a kind of liberation, as the gay brigade emerged from the bars, back rooms, and bedrooms of the Village and became street people.” In the manner of black power, the New Left, and radical feminists, homosexuals organized the Gay Liberation Front, voiced pride in being gay, and demanded equality of opportunity regardless of sexual orientation.

As with other oppressed groups, gays achieved victories slowly and unevenly. In the decades following the 1960s, gay men and lesbians faced discrimination in employment, could not marry or receive domestic benefits, and were subject to violence for public displays of affection.

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 880

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 652

Chapter Timeline