The Persistence of Liberalism

Despite the growing conservatism, political activism did not die out in the 1970s. Many of the changes sought by liberals and radicals during the 1960s had entered the political and cultural mainstreams in the 1970s. The counterculture, with its long hairstyles and colorful clothes, also entered the mainstream, and rock continued to dominate popular music. Some Americans experimented with recreational drugs, and the remaining sexual taboos of the 1960s fell. Many parents became resigned to seeing their daughters and sons living with boyfriends or girlfriends before getting married. And many of those same parents engaged in extramarital affairs or divorced their spouses. The divorce rate increased by 116 percent in the decade after 1965; in 1979 the rate peaked at 23 divorces per 1,000 married couples.

The antiwar movement and counterculture influenced popular culture in many ways. Rock musicians such as Bruce Springsteen, Jackson Browne, and Billy Joel sang of loss, loneliness, urban decay, and adventure. The film M*A*S*H (1970), though dealing with the Korean War, was a thinly veiled satire of the horrors of the Vietnam War, and in the late 1970s filmmakers began producing movies specifically about Vietnam and the toll the war took on ordinary Americans who served there. The television sitcom All in the Family gave American viewers the character of Archie Bunker, an opinionated, white, blue-collar worker, in a comedy that dramatized the contemporary political and cultural wars as conservative Archie taunted his liberal son-in-law with politically incorrect remarks about minorities, feminists, and liberals.

In the 1970s the women’s movement gained strength, but it also attracted powerful opponents. The 1973 Supreme Court victory for abortion rights in Roe v. Wade did not end the controversy. In 1976 Congress responded to abortion opponents by passing legislation prohibiting the use of federal funds for impoverished women seeking to terminate their pregnancies.

Feminists engaged in other debates in this decade, often clashing with more conservative women. The National Organization for Women (NOW) and its allies succeeded in getting thirty-five states out of a necessary thirty-eight to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), which prevented the abridgment of “equality of rights under law . . . by the United States or any State on the basis of sex.” In response, other women activists formed their own movement to block ratification. Phyllis Schlafly, a conservative activist, founded the Stop ERA organization to prevent the creation of a “unisex society.” Despite the inroads made by feminists, traditional notions of femininity appealed to many women and to male-dominated legislatures. The remaining states refused to ratify the ERA, thus killing the amendment in 1982, when the ratification period expired.

Despite the failure to obtain ratification of the ERA, feminists achieved significant victories. In 1972 Congress passed the Educational Amendments Act. Title IX of this law prohibited colleges and universities that received federal funds from discriminating on the basis of sex, leading to substantial advances in women’s athletics. Many more women sought relief against job discrimination through the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, resulting in major victories. NOW membership continued to grow, and the number of battered women’s shelters and rape crisis centers multiplied in towns and cities across the country. Women saw their ranks increase on college campuses, in both undergraduate and professional schools. Women also began entering politics in greater numbers, especially at the local and state levels. At the national level, women such as Shirley Chisholm and Geraldine Ferraro of New York, Barbara Jordan of Texas, and Patricia Schroeder of Colorado won seats in Congress. Membership in women’s political associations—such as Emily’s List, founded in 1984, and the Fund for a Feminist Majority, founded in 1987—soared, especially after Anita Hill testified against the nomination of Clarence Thomas to the Supreme Court.

Explore

See Documents 27.2 and 27.3 for two views of feminism by women of color.

At the same time, women of color sought to broaden the definition of feminism to include struggles against race and class oppression as well as sex discrimination. In 1974 a group of black feminists, led by author Barbara Smith, organized the Combahee River Collective and proclaimed: “We . . . often find it difficult to separate race from class from sex oppression because in our lives they are most often experienced simultaneously.” Chicana and other Latina feminists also sought to extend women’s liberation beyond the confines of the white middle class. In 1987 feminist poet and writer Gloria Anzaldúa wrote: “Though I’ll defend my race and culture when they are attacked by non-mexicanos . . . I abhor some of my culture’s ways, how it cripples its women . . . our strengths used against us, lowly [women] bearing humility with dignity.”

Another outgrowth of 1960s liberal activism that flourished in the 1970s was the effort to clean up and preserve the environment. The publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring in 1962 had renewed awareness of what Progressive Era reformers called conservation. Carson expanded the concept of conservation to include ecology, which addressed the relationships of human beings and other organisms to their environments. By exploring these connections, she offered a revealing look at the devastating effects of pesticides on birds and fish, as well as on the human food chain and water supply.

This new environmental movement not only focused on open spaces and national parks but also sought to publicize urban environmental problems. By 1970, 53 percent of Americans considered air and water pollution to be one of the top issues facing the country, up from only 17 percent five years earlier. Responding to this shift in public opinion, in 1971 President Nixon established the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and signed the Clean Air Act, which regulated auto emissions.

Not everyone embraced environmentalism. As the EPA toughened emission standards, automobile manufacturers complained that the regulations forced them to raise prices and hurt an industry that was already feeling the threat of foreign competition, especially from Japan. Workers were also affected, as declining sales forced companies to lay off employees. Similarly, passage of the Endangered Species Act of 1973 pitted timber companies in the Northwest against environmentalists. The new law prevented the federal government from funding any projects that threatened the habitat of animals at risk of extinction.

Several disasters heightened public demands for stronger government oversight of the environment. In 1978 women living near Love Canal outside Niagara Falls, New York, complained about unusually high rates of illnesses and birth defects in their community. Investigations revealed that their housing development had been constructed on top of a toxic waste dump. This discovery spawned grassroots efforts to clean up this area as well as other contaminated communities. In 1980 President Carter and Congress responded by passing the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (known as Superfund) to clean up sites contaminated with hazardous substances. Further inquiries showed that the presence of such poisonous waste dumps disproportionately affected minorities and the poor. Critics called the placement of these waste locations near African American and other minority communities “environmental racism” and launched a movement for environmental justice.

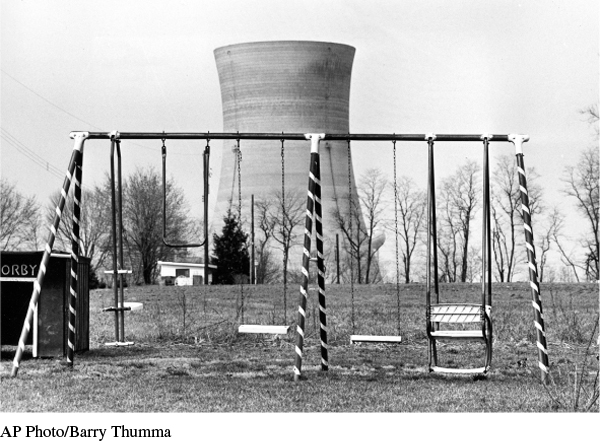

The most dangerous threat came in March 1979 at the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. A broken valve at the plant leaked coolant and threatened the meltdown of the reactor’s nuclear core. As officials quickly evacuated residents from the surrounding area, employees at the plant narrowly averted catastrophe by fixing the problem before an explosion occurred. Grassroots activists protested and raised public awareness against the construction of additional nuclear power facilities.

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 908

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 671

Chapter Timeline