Racial Struggles Continue

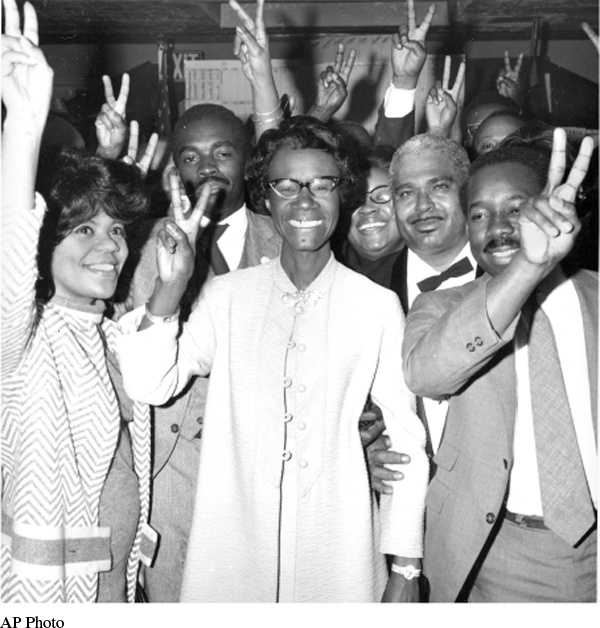

The civil rights struggle also did not end with the 1960s. The civil rights coalition of organizations that banded together in the 1960s had disintegrated, but the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People remained active, as did local organizations in communities nationwide. Following passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, electoral politics became the new form of activism. By 1992 there were more than 7,500 black elected officials in the United States. Many of them had participated in the civil rights movement and subsequently worked to gain for their constituents the economic benefits that integration and affirmative action had not yet achieved. During this time, the number of Latino American and Asian American elected officials also increased.

The issue of school busing highlighted the persistence of racial discrimination. In the fifteen years following the landmark 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, few schools had been integrated. Starting in 1969, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that genuine racial integration of the public schools must no longer be delayed. In 1971 the Court went even further in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education by requiring school districts to bus pupils to achieve integration. Cities such as Charlotte, North Carolina; Lexington, Kentucky; and Tampa, Florida, embraced the ruling and carefully planned for it to succeed.

However, the decision was more controversial in other municipalities around the nation and it exposed racism as a national problem. In many northern communities racially discriminatory housing policies created segregated neighborhoods and, thus, segregated schools. When white parents in the Detroit suburbs objected to busing their children to inner-city, predominantly black schools, the Supreme Court in 1974 departed from the Swann case and prohibited busing across distinct school district boundaries. This ruling created a serious problem for integration efforts because many whites were fleeing the cities and moving to the suburbs where few blacks lived.

As the conflict over school integration intensified, violence broke out in communities throughout the country. In Boston, Massachusetts, busing opponents tapped into the racial and class resentments of the largely white working-class population of South Boston, which was paired with the black community of Roxbury for busing, leaving mainly middle- and upper-class white communities unaffected. In the fall of 1974, battles broke out inside and outside the schools. Despite the violence, schools stayed open, and for the next three decades Boston remained under court order to continue busing.

Along with busing, affirmative action generated fierce controversy, as the case of Allan Bakke showed. From 1970 to 1977, with the acceleration of affirmative action programs, the number of African Americans attending college doubled, constituting nearly 10 percent of the student body, a few percentage points lower than the proportion of blacks in the national population. Though blacks still earned lower incomes than the average white family, black family income as a percentage of white family income had grown from 55.1 percent in 1965 to 61.5 percent ten years later. African Americans, however, still had a long way to go to catch up with whites. The situation was even worse for those who did not reach middle-class status: About 30 percent of African Americans slid deeper into poverty during the decade.

Despite the persistence of economic inequality, many whites believed that affirmative action placed them at a disadvantage with blacks in the educational and economic marketplaces. In particular, many white men condemned policies that they thought recruited blacks at their expense. Polls showed that although most whites favored equal treatment of blacks, they disapproved of affirmative action as a form of “reverse discrimination.”

The furor over affirmative action did not end with the Bakke case, and over the next three decades affirmative action opponents succeeded in narrowing the use of racial considerations in employment and education. However, they did so without Allan Bakke, who chose to live a private life with his family rather than campaign against affirmative action.

REVIEW & RELATE

What issues and trends shaped the presidency of Jimmy Carter?

How and why did the social and cultural developments of the 1960s continue to create conflict and controversy in the 1970s?

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 910

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 674

Chapter Timeline