Reagan and Reaganomics

Ronald Reagan’s presidential victory in 1980 consolidated the growing New Right coalition and reshaped American politics for a generation to come. The former movie actor had transformed himself from a New Deal Democrat into a conservative Republican politician when he ran for governor of California in 1966. As governor, he implemented conservative ideas of free enterprise and small government and denounced Johnson’s Great Society for threatening private property and individual liberty. His support for conservative economic and social issues carried him to the presidency.

Explore

For Ronald Reagan’s view of America, see Document 27.4.

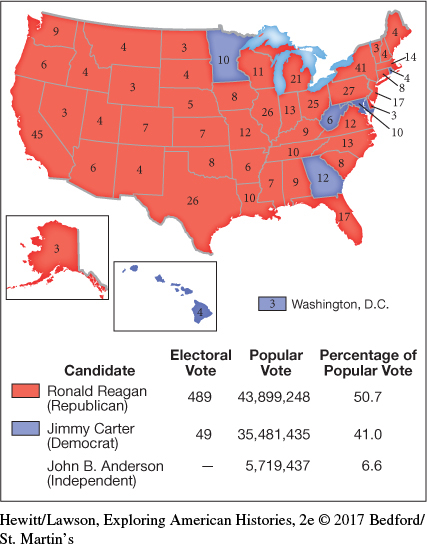

Reagan handily beat both Jimmy Carter and John Anderson, a moderate Republican who ran as an independent candidate (Map 27.3). The high unemployment and inflation of the late 1970s worked in Reagan’s favor. Reagan appealed to a coalition of conservative Republicans and disaffected Democrats, promising to cut taxes and reduce spending, to relax federal supervision over civil rights programs, and to end what was left of expensive Great Society measures and affirmative action. Finally, he energized members of the religious right, who flocked to the polls to support Reagan’s demands for voluntary prayer in the public schools, defeat of the Equal Rights Amendment, and a constitutional amendment to outlaw abortion.

Reagan’s first priority, however, was stimulating the stagnant economy. The president’s strategy, known as Reaganomics, reflected the ideas of supply-side economists and conservative Republicans. Reagan subscribed to the idea of trickle-down economics in which the gains reaped at the top of a strong economy would trickle down to the benefit of those below, thus reducing the need for large government social programs. Stating that “government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem,” Reagan asked Congress for a huge income tax cut of 30 percent over three years, a reduction in spending for domestic programs of more than $40 billion, and new monetary policies to lower rising rates for loans.

The president did not operate in isolation from the rest of the world. He learned a great deal from Margaret Thatcher, the British prime minister who took office two years before Reagan. Thatcher combated inflation by slashing welfare programs, selling off publicly owned companies, and cutting back health and education programs. An advocate of supply-side economics, Thatcher reduced income taxes on the wealthy by more than 50 percent to encourage new investment. West Germany also moved toward the right under Chancellor Helmut Kohl, who reined in welfare spending. In the 1980s Reaganomics and Thatcherism dominated the United States and the two most powerful nations of Western Europe.

In March 1981 Reagan survived a nearly fatal assassin’s bullet. More popular than ever after his recovery, the president persuaded the Democratic House and the Republican Senate to pass his economic measures in slightly modified form in the Economic Recovery Tax Act. These cuts in taxes and spending did not produce the immediate results Reagan sought—unemployment rose to 9.6 percent in 1983 from 7.1 percent in 1980. However, the government’s tight money policies, as engineered by the Federal Reserve Board, reduced inflation from 14 percent in 1980 to 4 percent in 1984. By 1984 the unemployment rate had fallen to 7.5 percent, while the gross national product grew by a healthy 4.3 percent, an indication that the recession of the previous two years had ended.

The success of Reaganomics came at the expense of the poor and the lower middle class. The president reduced spending for food stamps, school lunches, Aid to Families with Dependent Children (welfare), and Medicaid, while maintaining programs that middle-class voters relied on, such as Medicare and Social Security. However, rather than diminishing the government, the savings that came from reduced social spending went into increased military appropriations. Together with lower taxes, these expenditures benefited large corporations that received government military contracts and favorable tax write-offs.

As a result of Reagan’s economic policies, financial institutions and the stock market earned huge profits. The Reagan administration relaxed antitrust regulations, encouraging corporate mergers to a degree unseen since the Great Depression. Fueled by falling interest rates, the stock market created wealth for many investors. The number of millionaires doubled during the 1980s, as the top 1 percent of families gained control of 42 percent of the nation’s wealth and 60 percent of corporate stock. Reflecting this phenomenal accumulation of riches, television produced melodramas depicting the lives of oil barons (such as Dallas and Dynasty), whose characters lived glamorous lives filled with intrigue and extravagance. In Wall Street (1987), a film that captured the money ethic of the period, the main character utters the memorable line summing up the moment: “Greed, for lack of a better word, is good. Greed is right. Greed works.”

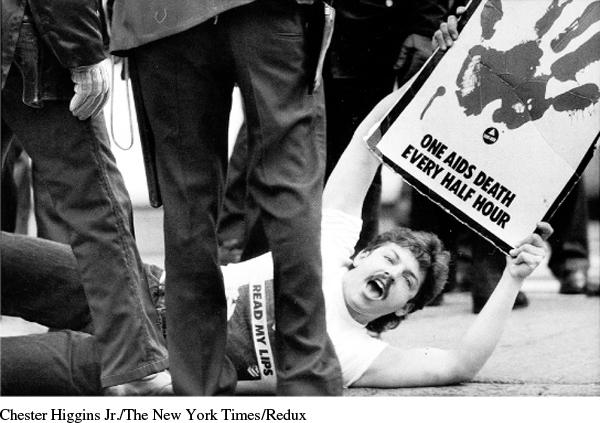

At the same time that a small number of Americans grew wealthier, the gap between the rich and the poor widened. Contrary to the promises of Reaganomics, the wealth did not trickle down. During the 1980s, the nation’s share of poor people rose from 11.7 percent to 13.5 percent, representing 33 million Americans. Severe cutbacks in government social programs such as food stamps worsened the plight of the poor. Poverty disproportionately affected women and minorities. The number of homeless people grew to as many as 400,000 during the 1980s. The middle class also diminished from a high of 53 percent of families in the early 1970s to 49 percent in 1985.

The Reagan administration’s relaxed regulation of the corporate sector also contributed to the unbalanced economy. The president aided big business by challenging labor unions. In 1981 air traffic controllers went on strike to gain higher wages and improved safety conditions. In response, the president fired the strikers who refused to return to work, and in their place he hired new controllers. Reagan’s anti-union actions both reflected and encouraged a decline in union membership throughout the 1980s, with union membership falling to 16 percent, its lowest level since the New Deal. Without union protection, wages failed to keep up with inflation, further increasing the gap between rich and poor.

Reagan continued the business deregulation initiated under Carter. Federal agencies concerned with environmental protection, consumer product reliability, and occupational safety saw their key functions shifted to the states, which made them less effective. Reagan also extended banking deregulation, which encouraged savings and loan institutions (S&Ls) to make risky loans to real estate ventures. When real estate prices began to tumble, savings and loan associations faced collapse and Congress appropriated over $100 billion to rescue them. Notwithstanding deregulation and small-government rhetoric, the number of federal government employees actually increased under Reagan by 200,000.

Reagan’s landslide victory over Democratic candidate Walter Mondale in 1984 sealed the national political transition from liberalism to conservatism. Voters responded overwhelmingly to the improving economy, Reagan’s defense of traditional social values, and his boundless optimism about America’s future. Despite the landslide, the election was notable for the nomination of Representative Geraldine Ferraro of New York as Mondale’s Democratic running mate, the first woman to run on a major party ticket for national office.

Reagan’s second term did not produce changes as significant as did his first term. Democrats still controlled the House and in 1986 recaptured the Senate. The Reagan administration focused on foreign affairs and the continued Cold War with the Soviet Union, thus escalating defense spending (see “‘The Evil Empire’” in chapter 28). Most of the Reagan economic revolution continued as before, but with serious consequences. Supply-side economics failed to support the increase in military spending: The federal deficit mushroomed, and by 1989 the nation was saddled with a $2.8 trillion debt, a situation that jeopardized the country’s financial independence and the economic well-being of succeeding generations.

The president further reshaped the future through his nominations to the U.S. Supreme Court. Starting with the choice of Sandra Day O’Connor, the Court’s first female justice, in 1981, Reagan’s appointments moved the Court in a more conservative direction. The elevation of Associate Justice William Rehnquist to chief justice in 1986 reinforced this trend, which would have significant consequences for decades to come.

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 916

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 677

Chapter Timeline