Bush and Compassionate Conservatism

In 2000 the Democratic candidate, Vice President Al Gore, ran against George W. Bush, the Republican governor of Texas and son of the forty-first president. Gore ran on the coattails of the Clinton prosperity, endorsed affirmative action, supported women’s reproductive rights, and warned of the need to protect the environment. Presenting himself as a “compassionate conservative,” Bush opposed abortion, gay rights, and affirmative action while advocating faith-based reform initiatives in education and social welfare. Also in the race was Ralph Nader, an anti-corporate activist who ran under the banner of the Green Party, a party formed in 1991 to support grassroots democracy, environmentalism, social justice, and gender equality.

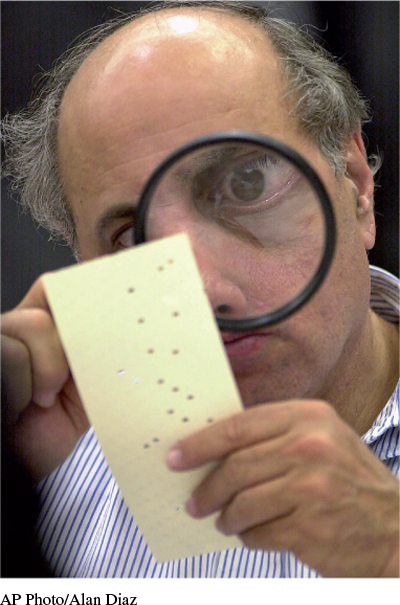

Nader’s candidacy drew votes away from Gore, but fraud and partisanship hurt the Democrats even more. Gore won a narrow plurality of the popular vote (48.4 percent, compared with 47.8 percent for Bush and 2.7 percent for Nader). However, Bush won a slim majority of the electoral votes: 271 to 267. The key state in this Republican victory was Florida, where Bush outpolled Gore by fewer than 500 popular votes. Counties with high proportions of African Americans and the poor, who were more likely to support Gore, encountered significant difficulties and outright discrimination in voting. When litigation over the recount reached the U.S. Supreme Court in December 2000, the Court, which included conservative justices appointed by Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush, proclaimed Bush the winner.

George W. Bush did not view his slim, contested victory cautiously. Rather, he appealed to his conservative political base by governing as boldly as if he had received a resounding electoral mandate. While Republicans still controlled the House, the Democrats had gained a one-vote majority in the Senate.

The president promoted the agenda of the evangelical Christian wing of the Republican Party. He spoke out against gay marriage, abortion, and federal support for stem cell research, a scientific procedure that used discarded embryos to find cures for diseases. Bush created a special office in the White House to coordinate faith-based initiatives, providing religious institutions with federal funds for social service activities without violating the First Amendment’s separation of church and state.

Attending to the faithful made for good politics. At the turn of the twenty-first century, a growing number of churchgoers were joining megachurches. These congregations, mainly Protestant, each contained 2,000 or more worshippers. Between 1970 and 2005, the number of megachurches jumped from 50 to more than 1,300, with California, Texas, and Florida taking the lead. The establishment of massive churches was part of a worldwide movement, with South Korea home to the largest congregation. Joel Osteen—the evangelical pastor of Lakewood Church in Houston, Texas, the largest megachurch in the United States—drew average weekly audiences of 43,000 people, with sermons available in English and Spanish. Preaching in a former professional basketball arena and using the latest technology, Osteen stood under giant video screens that projected his image. Such religious leaders held sway with large groups of voters who could be mobilized to significant political effect.

While courting such people of faith, Bush did not neglect economic conservatives. The Republican Congress gave the president tax-cut proposals to sign in 2001 and 2003, measures that favored the wealthiest Americans. Yet to maintain a balanced budget, the cardinal principle of fiscal conservatism, these tax cuts would have required a substantial reduction in spending, which Bush and Congress chose not to do. Furthermore, continued deregulation of business encouraged unsavory activities that resulted in corporate scandals and risky financial practices.

At the same time, Bush showed the compassionate side of his conservatism. Like Clinton’s, Bush’s cabinet appointments reflected racial, ethnic, and sexual diversity. They included African Americans as secretary of state (Colin Powell), national security adviser (Condoleezza Rice, who later succeeded Powell as secretary of state), and secretary of education (Rod Paige). In addition, the president chose women to head the Departments of Agriculture, Interior, and Labor and also appointed one Latino and two Asian Americans to his cabinet.

In 2002 the president signed the No Child Left Behind Act, which raised federal appropriations for the education of students in primary and secondary schools, especially in underprivileged areas. The law imposed federal criteria for evaluating teachers and school programs, relying on standardized testing to measure success. Another display of compassionate conservatism came in the 2003 passage of the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act. The law aimed to lower the cost of prescription drugs to some 40 million senior citizens enrolled in Medicare and received support from the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP).

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 976

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 722

Chapter Timeline