Introduction to Chapter 2

2

Colonization and Conflicts

1550–1680

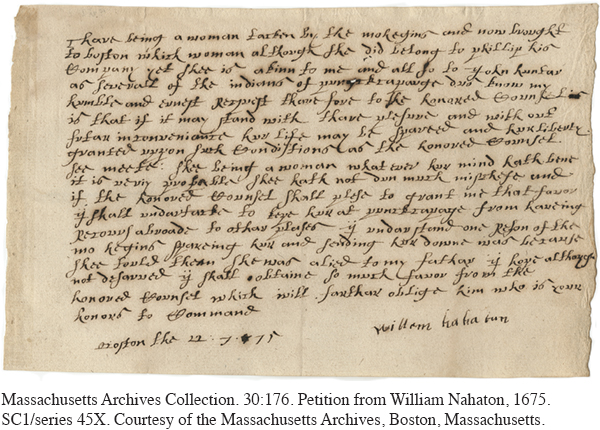

WINDOW TO THE PAST

William Nahaton, Petition to Free an Indian Slave, 1675

William Nahaton, a Christianized Indian in Massachusetts Bay, sent this petition to gain the release of a relative whom he feared would be sold into slavery by the English. While hundreds of native people were sold into slavery, petitions for their release were rare. This petition offers important insights into the views of an Indian who had chosen to adopt many English ways. To discover more about what this primary source can show us, see Document 2.5.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

Understand the impact of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation on European nations and their imperial goals in the American colonies.

Identify the ways that England’s hopes for its North American colonies were transformed by relations with Indians, upheavals among indentured servants, the development of tobacco, and the emergence of slavery.

Discuss the influence of Puritanism on New England’s development and how religious and political upheavals in England fueled Puritan expansion and conflicts with Indians in the colonies.

AMERICAN HISTORIES

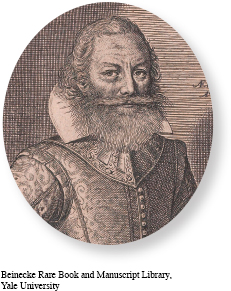

Born in 1580 to a yeoman farm family in Lincolnshire, John Smith left England as a young man “to learne the life of a Souldier.” After fighting and traveling in Europe, the Mediterranean, and North Africa for several years, Captain Smith returned to England around 1605. There he joined the Virginia Company, whose wealthy investors planned to establish a private settlement on mainland North America. In April 1607, Captain Smith and 104 men arrived in Chesapeake Bay, where they founded Jamestown, named in honor of King James I, and claimed the land for themselves and their country. However, the area was already controlled by a powerful Indian leader, Chief Powhatan.

In December 1607, when Powhatan’s younger brother discovered Smith and two of his Jamestown comrades in the chief’s territory, the Indians executed the two comrades but eventually released Smith. It is likely that before sending him back to Jamestown, Powhatan performed an adoption ceremony in an effort to bring Smith and the English under his authority. A typical ceremony would have involved Powhatan sending out one of his daughters—in this case, Pocahontas, who was about twelve years old—to indicate that the captive was spared. Refusing to accept his new status, if he understood it, Smith returned to Jamestown and urged residents to build fortifications for security.

The following fall, the colonists elected Smith president of the Jamestown council. Smith insisted that intimidating the Indians was the way to win Powhatan’s respect. He also demanded that the English labor on farms and fortifications six hours a day. Many colonists resisted. Those who claimed the status of gentlemen considered manual labor beneath them, and the many who were adventurers sought wealth and glory, not hard work. The Virginia Company soon replaced Smith with a new set of leaders. In October 1609, angry and bitter, he returned to England.

Captain Smith published his criticisms of Virginia Company policies in 1612, which brought him widespread attention. He then set out to map the Atlantic coast farther north. In 1616 Smith published a tract that emphasized the similarity of the area’s climate and terrain to the British Isles, calling it New England. He argued that colonies there could be made commercially viable but that success depended on recruiting settlers with the necessary skills and offering them land and a say in the colony’s management.

English men and women settled New England in the 1620s, but they sought religious sanctuary, not commercial success or military dominance. Yet they, too, suffered schisms in their ranks. Anne Hutchinson, a forty-five-year-old wife and mother, was at the center of one such division. Born in Lincolnshire in 1591, Anne was well educated when she married William Hutchinson, a merchant, in 1612. The Hutchinsons and their children began attending Puritan sermons and by 1630 embraced the new faith. Four years later, they followed the Reverend John Cotton to Massachusetts Bay.

The Reverend Cotton soon urged Anne Hutchinson to use her exceptional knowledge of the Bible to hold prayer meetings in her home on Sundays for pregnant and nursing women who could not attend regular services. Hutchinson, like Cotton, preached that individuals must rely solely on God’s grace rather than a saintly life or good works to ensure salvation.

Hutchinson began challenging Puritan ministers who opposed this position, charging that they posed a threat to their congregations. She soon attracted a loyal and growing following that included men as well as women. Puritan leaders met in August 1637 to denounce Hutchinson’s views and condemn her meetings. In November 1637, after she refused to recant, she was put on trial. Hutchinson mounted a vigorous defense. Unmoved, the Puritan judges convicted her of heresy and banished her from Massachusetts Bay. Hutchinson and her family, along with dozens of followers, then settled in the recently established colony of Rhode Island.

The American histories of John Smith and Anne Hutchinson illustrate the diversity of motives that drew English men and women to North America in the seventeenth century. Smith led a group of artisans, gentlemen, and adventurers whose efforts to colonize Virginia were in many ways an extension of a larger competition between European states. Hutchinson’s journey to North America was rooted in the Protestant Reformation, which divided Europe into rival factions. Yet as different as these two people were, both furthered English settlement in North America even as they generated conflict within their own communities. Communities like theirs also confronted the expectations of diverse native peoples and the colonial aspirations of other Europeans while reshaping North America between 1550 and 1680.

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 37

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 28

Chapter Timeline